“I have called this principle, by which each slight variation, if useful, is preserved, by the term of Natural Selection.”

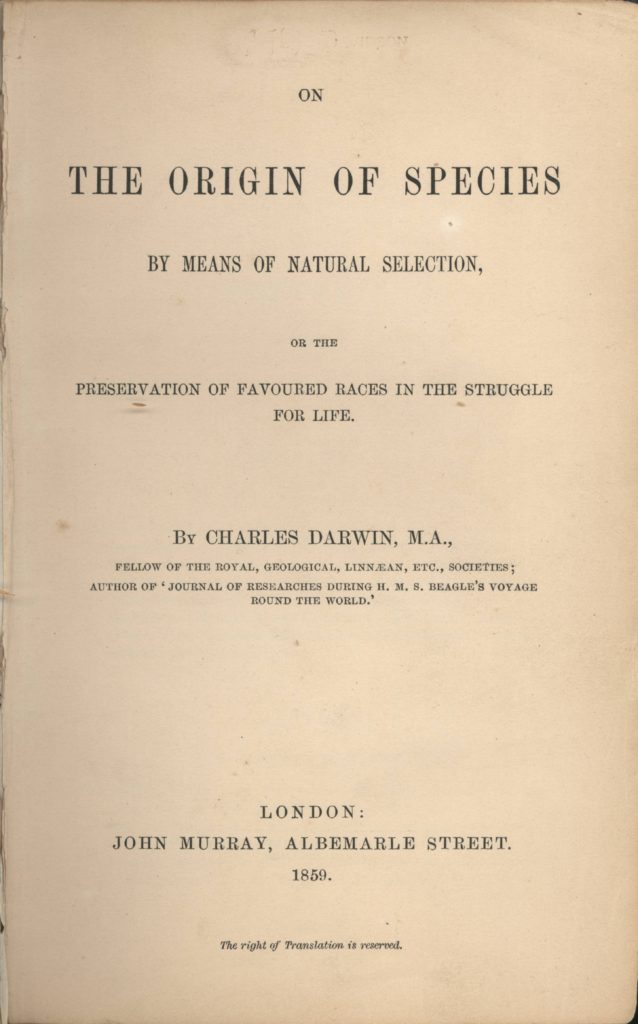

And so, in one brief sentence—and one long book—Charles Darwin changed our understanding of the world. That long book was published on November 24, 1859. Its proper title is On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life, a fittingly long title for a 502-page book The Origin of Species, as we shorten the title today, is undoubtedly the most important ecology book of all time and makes many lists of the most important books of all time, on any subject.

Darwin took his sweet time getting his ideas into print. He was born in 1802 (died 1882) to a cultured family, and was educated as a Victorian gentleman, spending time studying at Edinburgh and Cambridge. He drifted from subject to subject, but nature was clearly his core interest. When he was 22, an opportunity came his way to act on that interest. He was invited to join the voyage of the HMS Beagle as the gentleman companion of the caption, Robert Fitzroy. The rest, as they say, is history.

Darwin jumped at the chance. He spent the next five years on geological and biological expeditions throughout South America. As a gentleman passenger, he did as he liked, spending months at a time on land, exploring the continent (he only spent 18 months on board).. The observations he made and specimens he collected (770 pages of diary, 1750 pages of field notes, and 12 catalogues detailing 5,436 plants, animals, fossils and more) gave him a lifetime of material to consider.

By the time he returned to England in 1836, Darwin was already a scientific celebrity. He had dispatched many articles during the voyage, to be read at scientific meetings by his colleagues. He continued to write and think, his understanding of nature diverging more every year from the universal religious thought of the Victorian age—that a divine hand had created all species just as they are today. But Darwin knew that species changed over time and varied from one place to another—his observations of bird species on the Galapagos Islands and the fossils he collected were undeniable.

Darwin might never have published On the Origin of Species if he hadn’t been pushed. He was a cautious man who shrunk from argument and public debate, and his high status in society made him even more reluctant to risk his reputation by pushing unpopular ideas. He had spent two decades refining his ideas, and he was in no hurry to publish them. His plan was to produce a three-volume work that laid out all his ideas and evidence. But Darwin learned that a colleague and fellow South American explorer, Alfred Russel Wallace, had come to similar conclusions as his own. They published articles together in 1858 (and so are rightly considered the co-equal originators of the idea of natural selection), and then Darwin got down to work on a book that would beat Wallace to press.

On the Origin of Species was published on November 24, 1859, in an edition of 1500. The book sold out in one day. An edition of 3000 was issued in early January, and it sold out immediately. And, of course, the book has been in print continuously since then, selling countless millions and translated into many languages. A 2017 poll found On the Origin of Species to be the single most important academic in history; it is, they wrote, “a book which has changed the way we think about everything.” We are perhaps fortunate that Darwin didn’t have time to pen his planned three-volume work; as the famous botanist, Sir Joseph Hooker wrote to him, “…three volumes…would have choked any naturalist of the nineteenth century.”

In environmental matters, Darwin’s work is the undeniable foundation work of ecological science. The inter-relationships among organisms and their environments only matter if each can influence the other. But let’s allow Darwin himself to tell the story, as he did in the closing pages of On the Origin of Species:

“It is interesting to contemplate an entangled bank, clothed with many plants of many kinds, with birds singing on the bushes, with various insects flitting about, and with worms crawling through the damp earth, and to reflect that these elaborately constructed forms, so different from each other, and dependent on each other in so complex a manner, have all been produced by laws acting around us … Thus, from the war of nature, from famine and death, the most exalted object which we are capable of conceiving, namely, the production of the higher animals, directly follows. There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.”

References:

Darwin Online. On the Origin of Species. Available at: http://darwin-online.org.uk/EditorialIntroductions/Freeman_OntheOriginofSpecies.html. Accessed November 18, 2019.

Desmond, Adrian J. 2019. Charles Darwin, British Naturalist. Encyclopedia Britannica. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Charles-Darwin. Accessed November 18, 2019.

Flood, Alison. 2015. On the Origin of Species voted most influential academic book in history. The Guardian, 10 Nov 2015. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/nov/10/on-the-origin-of-species-voted-most-influential-academic-book-charles-darwin. Accessed November 18, 2019.