Once Darwinian evolution reached the status of a fact rather than a theory, scientists everywhere became committed to the idea that competition was the primary force causing species to evolve and radiate into new species. But in the late 1960s, a young scientist, un-phased by what everyone else thought, suggested that collaboration—symbiosis—was equally important in evolution. That scientist was Lynn Margulis.

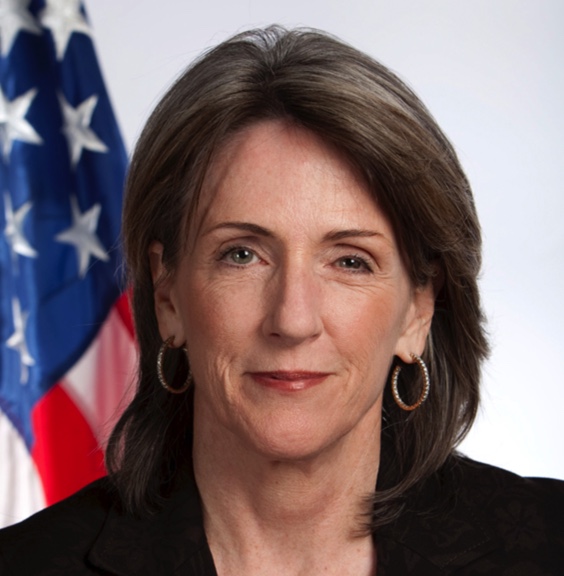

Lynn Margulis was born in Chicago on March 5, 1938 (died 2011). She was a child prodigy, entering the University of Chicago at age 14. She graduated five years later and married Carl Sagan, who would become the world’s most famous astronomer. The marriage lasted only a few years, during which Margulis bore two sons and pursued advanced degrees at the Universities of Wisconsin and California. She completed her doctorate in 1965 and began a scientific career first at Boston University and later at the University of Massachusetts.

She “led a life devoted to science.” Her paradigm-changing contribution came in her development of the theory of “serial endosymbiosis” during the late 1960s. Based on similarities between bacteria and the cell organelle mitochondrium, she surmised that mitochondria were first independent animals that eventually became incorporated into other single-celled organisms. She saw other common attributes of cell organelles and independent organisms as other examples of the same idea. By joining forces, the new organism was better able to exploit its environment and succeed. Just like competition, symbiosis led to new forms of life.

For a decade her idea was considered nonsense. She was called a radical, her ideas judged with doubt and ridicule. Her first paper describing endosymbiosis was rejected by 15 journals before being published in 1967 by the Journal of Theoretical Biology. As more evidence accumulated, her theory went from radical to accepted and she went from contrarian to a leader of evolutionary thought. Today, endosymbiosis is taught alongside competition from middle school to graduate school.

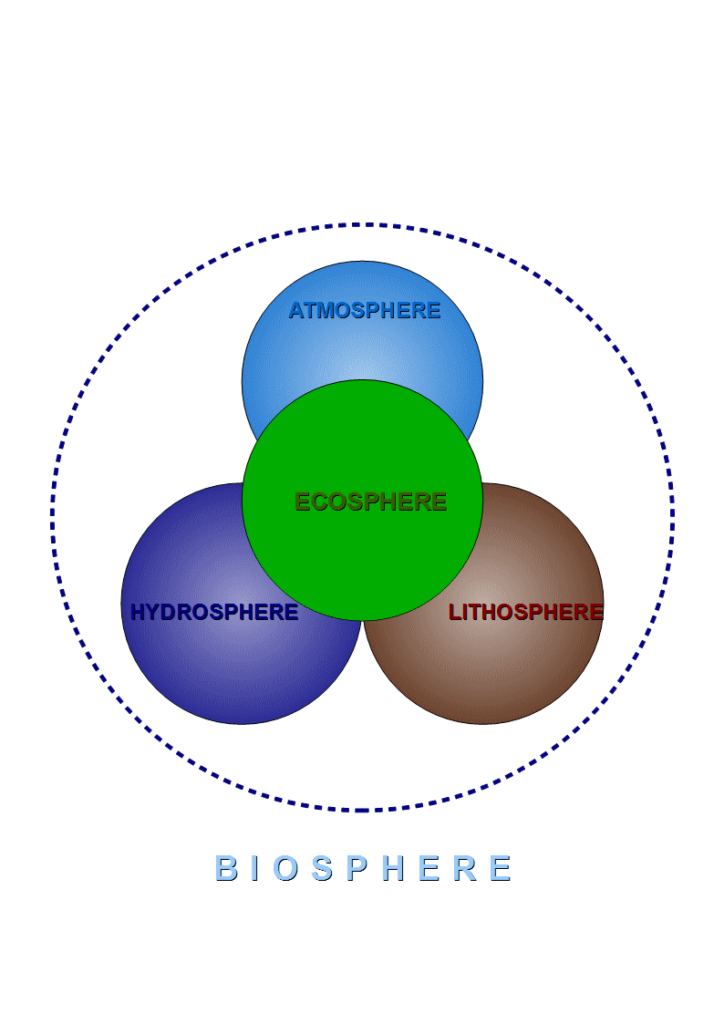

She was also a proponent of the “Gaia Hypothesis,” originally devised by James Lovelock. The Gaia idea is that not only does the environment affect organisms, but that organisms also affect the environment. These mutual interactions work together to create and modify the biosphere to maintain life, forming a gigantic self-regulating system. The idea is named for Gaia, in Greek mythology the mother of all life. By adding a feedback loop from organism to environment, the Gaia concept imagines the organisms as not just the recipient of evolutionary forces, but also the driver of environmental change.

Margulis became one of the most honored biologists of her time. She wrote many books on a wide range of topics, most with her eldest son, Dorion, as co-author. She was as committed to public understanding of science as she was to advancing scientific research. An English newspaper described her as “a charismatic lecturer to audiences at all levels,” known for “enthusiastically and generously developing experiments that schoolchildren could carry out….” Her books included popular coverage of topics such as climate change, sex and natural design.

Regardless of the criticisms, the Gaia hypothesis and Margulis’s other interpretations of the living earth have provided a “big picture” for framing our relationship with the earth and our co-inhabitants. She believed that collaboration, rather than competition and dominance, were essential to survival. That is one reason Science magazine called her “science’s unruly Earth mother.” To me, it sounds like another definition of sustainability. And so I say, three cheers for motherhood!

References:

Glorfeld, Jeff. 2018. Science history: Lynn Margulis, contrarian to the end. Cosmos, The Science of Everything, 23 November 2018. Available at: https://cosmosmagazine.com/biology/science-history-lynn-margulis-contrarian-to-the-end. Accessed March 1, 2019.

Rose, Stephen. 2011. Lynn Margulia obituary. The Guardian, 11 Dec 2011. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/science/2011/dec/11/lynn-margulis-obtiuary. Accessed March 1, 2019.

Tao, Amy. 2019. Lynn Margulis, American Biologist. Encyclopedia Britannica. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Lynn-Margulis. Accessed March 1, 2019.