In the mid-1800s, the American west was a distant wilderness to most people. Americans, and the rest of the world, saw the landscape mostly through the works of artists who accompanied survey expeditions. Their often monumental and romanticized paintings fired the imagination of an “American Eden.” Perhaps the most famous of these artists, both at the time and still today, is Albert Bierstadt.

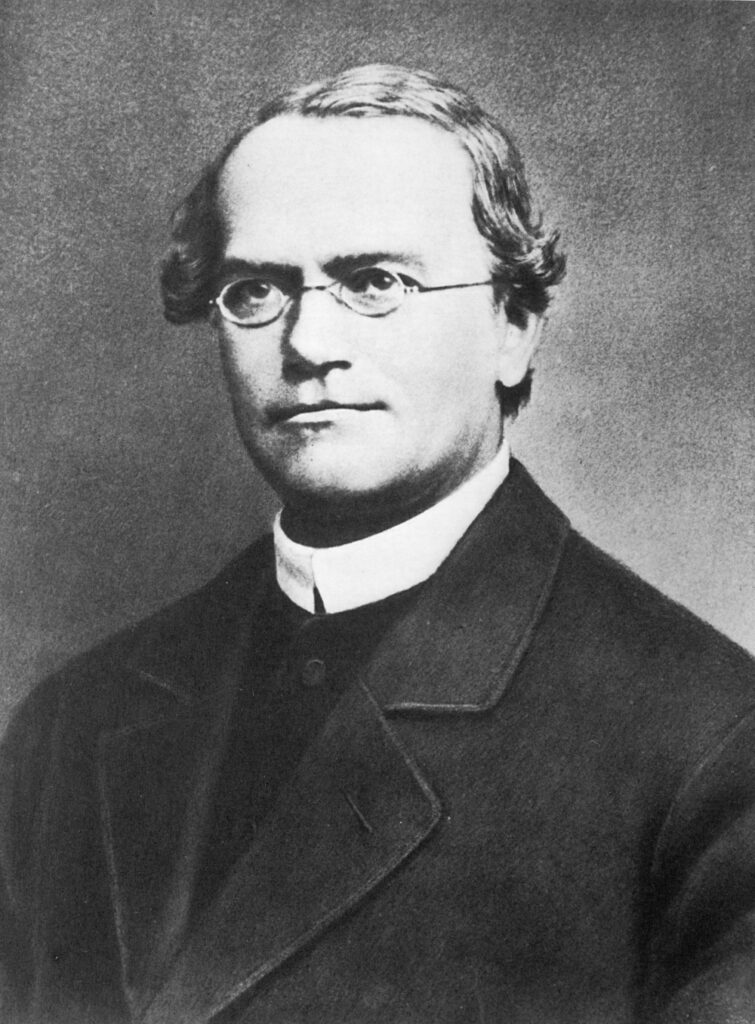

Albert Bierstadt was born on January 7, 1830 (died 1902), in Prussian Germany. His parents emigrated to New Bedford, Massachusetts, when Albert was just two years old. His father built barrels for the whaling industry, providing a comfortable childhood for Albert and his two brothers.

The boy was a natural artist, constantly sketching what he saw around him in the New England landscape. Little is known about his early life, but his skill at drawing led him to become an art teacher at age 20. Then, in 1853, he traveled to Germany, studying with experienced artists and sketching across Germany, Switzerland, and Italy for four years. He matured as an artist, demonstrating exceptional talent at representing the vertical landscapes of the Alps.

Once back in New Bedford, he began to exhibit his European work, gaining recognition for his luminous use of light and color that produced serene and gentle landscapes. He traveled throughout New England, and like other artists of the Hudson River School, he painted highly evocative and idealized American landscapes.

Bierstadt, however, along with others including Thomas Moran, became enthralled by the landscape of the American West. During 1857-1859, he took two trips, making countless sketches and experimenting with the new field of photography. He travels convinced him that the American West “has the best material for the artist in the world.” He took a studio in New York City and, using the sketches from his travels, began painting the large canvases for which he became famous. He used the techniques he honed painting in the Alps to produce mystical scenes based on recognizable landscapes but modified to evoke tranquility and majesty.

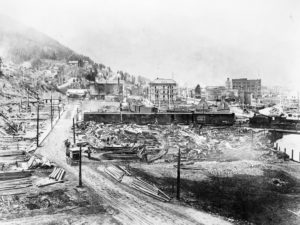

For the next several decades, Bierstadt took his place as one of the nation’s most revered landscape artists. His monumental canvases graced the U.S. capitol and the finest galleries across the nation (where they can still be seen today). He emphasized the grandeur of the natural environment, generally minimizing the presence of the human-built world. The popularity of his work is often credited with energizing the drive to protect western landscapes as national parks. He was also appalled by the destruction of American bison and other species. “The continual slaughter of native species,” he said, “must be halted before all is lost.”

In his later years, he spent parts of every year in the Bahamas, where his wife had moved for medical reasons. His paintings of tropical environments are generally considered of equal quality to those he painted of the American West.

Bierstadt’s popularity fell as the 20th Century approached, with critics dismissing his large canvases as overly sentimental. His reputation revived in the 1960s as the environmental movement renewed Americans interest in the need for protecting our great natural resources. Today his works occupy a prominent position as symbols of the majesty of the western landscape. As he said,“Truly all is remarkable and a wellspring of amazement and wonder. Man is so fortunate to dwell in this American Garden of Eden.”

References:

Albertbierstadt.org. Albert Bierstadt Biography in Details. Available at: https://www.albertbierstadt.org/biography.html. Accessed January 5, 2023.

National Gallery of Art. Albert Bierstadt. Available at: https://www.nga.gov/collection/artist-info.6707.html. Accessed January 5, 2023.

The Art Story. Albert Bierstadt. Available at: https://www.theartstory.org/artist/bierstadt-albert/. Accessed January 5, 2023.