I have written about the creation of several national parks and monuments that occurred on other days. Most begin with a story of local residents who loved the region and mounted a movement to create a park. But the origin of this park is much different.

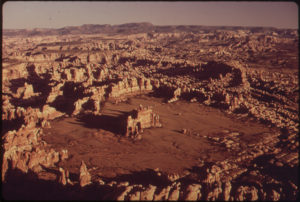

The area now occupied by Canyonlands National Park is in the remote southeastern corner of Utah. Remote is the right word—the human population is very low and the area of the park has had no human inhabitants in recent centuries. Ten thousand years ago, the Anasazi People lived there, and they left artifacts of their occupation—abandoned villages, rock pictures and other archeological items. But in recent times, this part of Utah was basically empty.

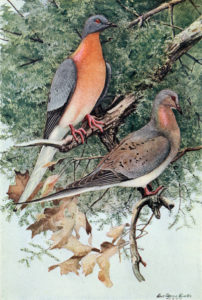

As the national park movement grew in the 20th Century, however, some folks began to take notice of the area’s dramatic geological formations. Relentless winds and rivers had carved amazing canyons into the sandstone earth. Among the canyons stood a wealth of stone arches and pinnacles, miraculously colored at sunrise and sunset. In the 1930s, Secretary of Interior Harold Ickes first proposed making the whole region a gigantic national park, but his idea faded as the country turned to higher priorities—escaping the Great Depression and winning World War II.

The idea arose again in the early 1960s. At that time, the National Park Service was asking park superintendents to recommend new national park sites, primarily because park popularity had soared, causing crowding and degradation at existing parks. The superintendent of nearby Arches National Monument, Bates Wilson, offered his suggestion—make a new park in the remote region where the Colorado and Green Rivers came together, and call it Canyonlands.

Wilson was a dogged advocate for the park. He brought politicians, community leaders and conservationists to the area for hikes, float trips and campfire dinners. In 1961, he hosted Secretary of Interior Stewart Udall on a five-day excursion. Like others, Udall was entranced by the region’s remote, rugged beauty. Immediately, Udall proposed a 1-million-acre park. Wilson also garnered the support of one of Utah’s senators, Frank Moss, who introduced legislation to create Canyonlands National Park in 1961.

Moss’ bill exploded into controversy. The other Utah Senator and the Utah governor were adamantly opposed. Ranchers and miners, who had permits to use lands within the proposed park, cried foul, and they were joined by others who didn’t like the idea of closing off a huge area from any commercial use. Utah politicians, and many citizens, disliked the idea of federal lands at all, believing the state should own public lands and make locally informed decisions about their use. For three years, the controversy roiled and various compromises were floated—a smaller park, a park surrounded by a multiple-use area, continued exploitation within a park by current permit holders and others. Fortunately, the Mormon Church sided with creating a park.

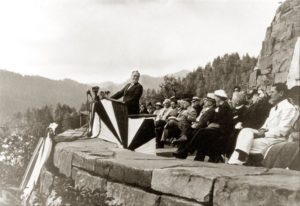

Udall, Moss and Wilson never waivered in their commitment to a great new park. Finally, in early 1964, Congress agreed on a bill that was signed on September 12 by President Lyndon Johnson. The bill states that Canyonlands possesses “superlative scenic, scientific, and archeologic features for the inspiration, benefit and use of the public….” In a concession to multiple use, the law allowed current holders of grazing permits to continue grazing for the length of their permits plus one renewal. All mining claims were also valid, but the promise of finding valuable resources—oil, minerals, uranium—has never been fulfilled. Today, neither grazing or mining interferes with the protection afforded a national park.

So, here is a national park that was created because the U.S. government said to its knowledgeable staff members, “Hey, go find us a great place to put a park.” Secretary Udall worked tirelessly for the park. Senator Moss later acknowledged that being known as “father of Canyonlands” was the highlight of his career.

And they did a fine job. Canyonlands protects about 337,000 acres of majestic scenery, which many people consider the equal of the Grand Canyon. Visitation has grown from about 20,000 in 1965 to about 750,000 today. And a trip to Canyonlands and its neighboring Utah national Parks is on many bucket lists. It is on mine, and I hope it is on yours.

References:

National Park Service. 2018. A Conversation with Bates Wilson. Available at: https://www.nps.gov/cany/learn/historyculture/bateswilson.htm. Accessed July 20, 2018.

National Park Service. Public Law 88-590. Available at: https://www.nps.gov/cany/learn/management/pl88-590.htm. Accessed July 20, 2018.

Smith, Thomas G. The Canyonlands National Park Controversy. Utah History to Go. Available at: https://historytogo.utah.gov/utah_chapters/utah_today/thecanyonlandsnationalparkcontroversy.html. Accessed July 20, 2018.