Today “Earth Day” is celebrated every year around the world on April 22. The day itself sprawls into celebrations of earth week, even earth month. From pre-schools to senior-citizen centers, as many as one billion people spend the day thinking about and acting on behalf of a sustainable environment. It started out much more simply.

Gaylord Nelson, liberal senator from Wisconsin, deserves the credit (learn more about Gaylord Nelson). As governor of Wisconsin and then as one of the state’s senators, Nelson was committed to conservation. Throughout the 1960s, he worried because “the state of our environment was simply a non-issue in the politics of the country.” Making it an issue became Nelson’s passion. He convinced President Kennedy to conduct a five-day “conservation tour” in 1963, to put the environment on reporters’ agendas. The result was modest and fleeting, so Nelson searched for a better strategy.

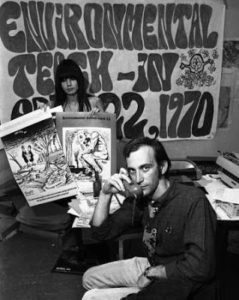

The idea of a massive “teach-in” about the environment occurred to him in 1969. He said, “…anti-Vietnam War demonstrations … had spread to college campuses all across the nation. Why not organize a huge, grass-roots protest about what was happening to our environment?” At a conference in Seattle that September, he announced the plan for an Earth Day the following spring. He chose April 22 because public schools would still be in session and colleges wouldn’t yet be in final exams.

The response, Nelson said “was electric; it took off like gangbusters.” He set up an office and hired a young man from Harvard, Denis Hayes, as national coordinator. Nelson and Hayes built a larger staff, raised money (the whole event cost less than $200,000) and spread materials and publicity. But this was obviously an idea whose time had come. The grassroots were sprouting. As Nelson wrote later, “It organized itself.”

On April 22, 1970, an estimated 20 million people rallied for the environment. Thousands of colleges held teach-ins and marches to protest the state of our environment. Similar events occurred in public schools and local communities. Everyone was on board. Congress suspended work for the day because so many members were participating in their home districts. It accomplished a rare victory—bi-partisanship. As the New York Times reported, “Conservatives were for it. Liberals were for it. Democrats, Republicans and independents were for it. So were the ins, the outs, the Executive and Legislative branches of government.”

The first Earth Day is heralded as the start of the “environmental decade” of the 1970s. Dozens of major laws at federal and state levels were established to protect air, water, soil, endangered species, wildlife habitat, parks and open space. In Nelson’s mind, though, the environment wasn’t just about wilderness and pretty scenery. He wrote, “Environment is all of America and its problems. It is rats in the ghetto. It is a hungry child in a land of affluence. It is housing not worthy of the name; neighborhoods not fit to inhabit.”

On the twentieth anniversary of Earth Day, in 1990, Denis Hayes organized another earth day, global this time. An estimated 200 million people in 141 countries participated. Since then, Earth Day has become an annual affair. The Earth Day Network estimates that now more than a billion people participate every year.

Senator Nelson never imagined it would be more than a one-time event. But he would be pleased. “The goal of Earth Day,” he wrote, “was to inspire a public demonstration so big it would shake the political establishment out of its lethargy and force the environmental issue onto the national political agenda.” It worked.

References:

Earth Day Network. The History of Earth Day. Available at: https://www.earthday.org/about/the-history-of-earth-day/. Accessed April 20, 2018.

Nelson, Gaylord. 2002. Beyond Earth Day; Fulfilling the Promise. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison. 201 pages.

Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies. Gaylord Nelson and Earth Day—the making of the modern environmental movement. University of Wisconsin, Madison. Available at: http://www.nelsonearthday.net/about/index.php. Accessed April 20, 2018.

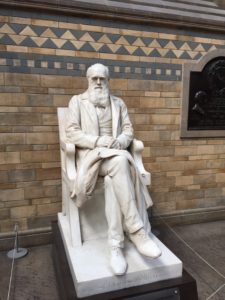

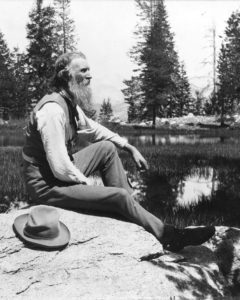

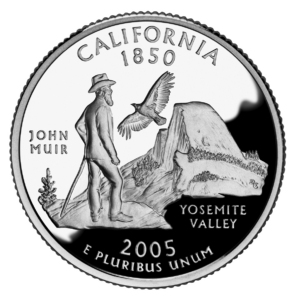

Muir was a complex man. He was deeply spiritual, but hated organized religion. He loved people individually and was the life of the party wherever he went, but he distrusted organizations of all kinds. He never considered himself a citizen of anything but the earth. He loved hiking in the wilderness alone, but craved the company of those he loved.

Muir was a complex man. He was deeply spiritual, but hated organized religion. He loved people individually and was the life of the party wherever he went, but he distrusted organizations of all kinds. He never considered himself a citizen of anything but the earth. He loved hiking in the wilderness alone, but craved the company of those he loved.