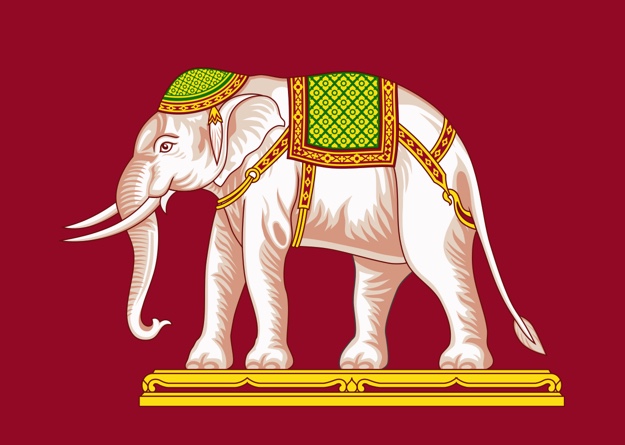

The national symbol of Thailand is the elephant, specifically the “white elephant.” The elephant was declared Thailand’s national animal on March 13, 1963. Later, in 1998, when the country decided that elephant protection required greater attention, it designated the same date—March 13—as National Elephant Day.

Thailand’s elephants are members of the Asian elephant species (Elephas maximus), the smaller of the earth’s two elephant species. Asian elephants can be domesticated and have been used by humans for thousands of years to perform work. The major role in Thailand has been in logging, where elephants were used to pull downed logs from the forest to places where they were further processed.

Beyond their use as work animals, elephants play an important cultural role in Thailand. As Buddhists, Thai citizens consider many animals sacred, including the elephant. The Buddhist god Ganesh, the symbol of wisdom, success and good luck, has a human body with an elephant head. White elephants, which are not albino but simply a lighter shade than the typical elephant, have been kept by Thai kings for centuries to symbolize their authority to reign. The white elephants was placed on the Thai flag in the early 1800s and remained there for a century.

Elephants were once abundant in the lush Thai forests, estimated to have numbered about 100,000 in 1900. Today fewer than 2,000 remain in the wild, affected mostly by the loss of habitat, along with overhunting for ivory. The species is classified as endangered by IUCN and is now protected throughout Thailand. Most wild elephants live in national parks or other preserves of natural forest.

About 3,000 elephants are held privately. Since logging of natural forests was outlawed in Thailand, however, the primary use of elephants in the forest industry has disappeared, leaving tourism as the predominant way in which elephants are used. Conditions for elephants in the tourist trade vary widely, from cruel and abusive handlers (especially in large cities) to centers that focus on ethical and humane interactions between people and elephants. Because of the long association between people and elephants, tourism is a major industry both for Thai citizens and for foreign visitors.

The principal elephant conservation program is operated through the Thai Elephant Conservation Center, a government-owned facility created in 1993 by the king. The center has about 50 elephants and offers opportunities for people to interact with and learn about elephants.

National Elephant Day was first celebrated in 1999. According to the organization Thailand Elephants, “[t]he day was made to celebrate and show how significant elephants are to Thailand, how the Thai culture depends on elephants and also to promote awareness about protecting and conserving the Thai elephants and their natural habitat.”

References:

Chiangrai Times. 2014. National Elephant Day Celebrated in Thailand. March 13, 2014. Available at: http://www.chiangraitimes.com/national-elephant-day-celebrated-in-thailand.html. Accessed march 12, 2018.

Elephant Conservation Center. The Elephant Conservation Center. Available at: http://www.thailandelephant.org/en/index.html. Accessed March 12, 2018.

Elephant Nature Park. Facts about Elephants. Available at: https://www.elephantnaturepark.org/about/facts-about-elephants/. Accessed March 12, 2018.

McCrea, Kerri. 2017. The National Elephant Day 2017! Available at: https://www.thailandelephants.org/single-post/2017/03/13/Thai-National-Elephant-DayChang-Thai- -2017. Accessed March 12, 2018.

Siwalai. Elephants in Thailand: Past and Present. Thaiways Magazine. Available at: https://www.thaiwaysmagazine.com/thai_article/2711_elephant_royal/elephant_royal.html. Accessed March 12, 2018.