President Theodore Roosevelt declared the creation of Muir Woods National Monument on January 9, 1908. The 1906 Antiquities Act provided the legal authority for establishment of national monuments by the president. Muir Woods became just the seventh national monument created in the United States.

Muir Woods lies just north of San Francisco, adjacent to Golden Gate National Recreation Area and surrounded by Mt. Tamalpais State Park. The monument was established by a gift from wealthy California businessman and conservationist, William Kent. In 1905, Kent purchased one of the few remaining stands of coastal redwoods, a 600+ acre tract that wound its way along Redwood Creek, for $45,000. The tract had escaped the logging that had downed most redwoods because the valley of Redwood Creek was nearly inaccessible. When his wife wondered if they had the money to spare, he told her, “If we lost all the money we have and saved these trees, it would be worthwhile, wouldn’t it?”

Muir Woods is famous for its grove of coastal redwood trees (Sequoia sempervirens), the world’s largest living tree. The tallest tree in Muir Woods is 250+ feet, but larger specimens exist farther north in California and southern Oregon. Most trees in Muir Woods are 600-800 years old; the oldest is around 1200 years old. Muir loved the fact that this grove was preserved, as he wrote to William Kent: “Saving these woods from the axe & saw, from money-changers and water-changers & giving them to our country & the world is in many ways the most notable service to God & man I’ve heard of since my forest wanderings began.”

When a downstream developer announced plans to flood Redwood Creek, the grove faced the threat of destruction. Kent acted quickly by donating 295 acres of his land to the federal government in 1907 for the purpose of creating a national monument. This action trumped local laws, effectively protecting the redwoods. President Roosevelt acted quickly to create the Muir Woods National Monument.

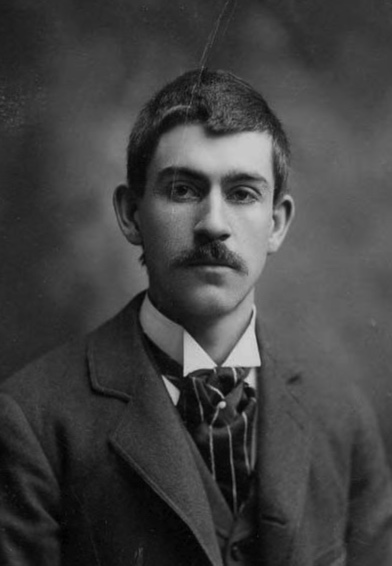

However, Roosevelt thought it would be more fitting to name the grove after the donor, William Kent, and wrote to seek his permission for the naming. Kent objected, writing to Roosevelt, “Your kind suggestion of a change of name is not one that I can accept. So many millions of better people have died forgotten, that to stencil one’s own name on a benefaction, seems to carry with it an implication of mandate immortality, as being something purchasable.”

Kent later became a U.S. congressman. While in congress, he introduced the legislation that created the National Park Service in 1916.

Muir Woods has received more than 1 million visitors annually since 2014, putting it in the top 20% of all national park units by visitation. Because of its popularity, parking is a major headache for visitors and for nearby residents. A reservation system is now in place to both limit access and assure visitors that they will get to see the redwood groves.

References:

National Park Service. Muir Woods. Available at: https://www.nps.gov/muwo/index.htm. Accessed January 8, 2017.