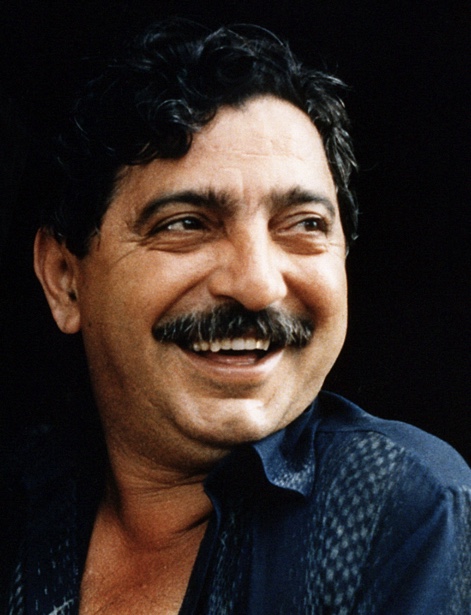

Chico Mendes, Brazilian rainforest advocate, was born December 15, 1944. Mendes was murdered three days before Christmas in 1988, the victim of animosity over his work to protect Brazilian rainforests from deforestation.

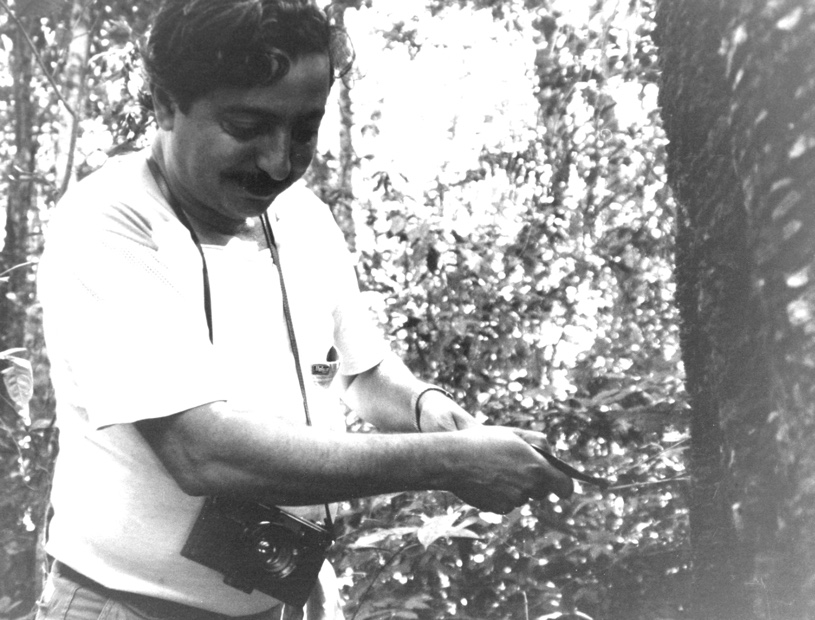

Francisco Alves Mendes Filho—always known as Chico—was born into a rubber-tapping family in the western border region of Brazil, in the state of Acre. Rubber-tapping is the process of cutting shallow groves in a rubber tree and collecting the sap that oozes out of the wound. Rubber-tapping began in the Amazon in the late 1880s, as uses of the sap as an industrial product became commonplace. The sap was melted into round balls about the size of a basketball over an open fire by the rubber tappers and sold to local wholesalers to export to Europe and America. The congealed sap—known as latex and later rubber—found worldwide use as the coating for waterproof clothing, insulation for electrical wires and the raw material of automobile tires.

The Brazilian state of Acre was the center of rubber tapping for many decades. Acre’s unusually fertile soils grew rubber trees to larger size and at higher densities than elsewhere in the rainforest. Mendes became a rubber tapper as a young boy, helping his family sustain a lifestyle based on tapping rubber, gathering Brazil nuts and subsistence hunting and farming. Like others in the area, Mendes and his family were dependent on having access to large tracts of virgin forestland, guaranteed to them by Brazilian law.

But desires by the government to make the rainforest more productive led to misguided policies to give large acreages to ranchers who began cutting down the forest in favor of cattle-grazing pastures. Mendes objected to this approach, and he organized labor unions of rubber tappers to fight what he considered illegal land grabs and logging.

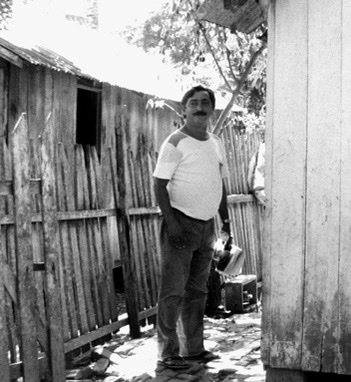

As Mendes’ advocacy succeeded and grew, he organized peaceful protests—called “empates”—staged to prevent logging from occurring on local lands. Along the way, he organized schools, medical clinics and other social improvement programs for rural communities, in concert with the progressive and liberal Catholic Church. These activities gradually gained the attention of the U.S. conservation community, which was looking for charismatic leaders who could put a human face on the rainforest conservation message. Chico Mendes fit the bill. Under sponsorship of the Environmental Defense Fund, Mendes traveled to the U.S. and England to promote rainforest protection.

Within Brazil, he developed the idea of “extractive reserves.” Rather than preserving the rainforest, Mendes opted for sustainable utilization, allowing rubber tappers and other rural residents to stay on the land and use it for traditional purposes. He convinced the World Bank and other development agencies to include extractive reserves as an element of their programs.

However popular this idea was to conservationists, it was equally hated by land developers in Brazil. On December 22, 1988, gunmen for an infamous Brazilian rancher and criminal shot and killed Mendes as he walked out of his back door to take a shower.

If the murder of Mendes was meant to stop efforts to preserve rainforests, it had exactly the opposite effect. Mendes’ death made global news and thousands attended his funeral on Christmas day. Extracted reserves are now a standard tool of conservation, and the nation of Brazil has adopted re-forestation, not de-forestation, as its official forest policy.

References:

Nielsen, Larry A. 2017. Nature’s Allies—8 Conservationists Who Changed Our World. Island Press, 255 pages.