The 2006 movie, “A Night at the Museum” introduced people around the world to the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. But the real museum is even more spectacular than the special effects of the movie—and has been for nearly 150 years.

The governor of New York signed the museum into existence on April 6, 1869. The mission, then and now, is straightforward: “To discover, interpret, and disseminate—through scientific research and education—knowledge about human cultures, the natural world, and the universe.”

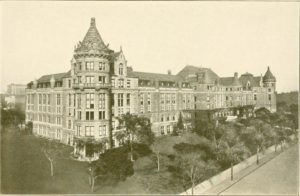

The founders wasted little time acting on their mission. Within two years, specimens from the museum went on exhibit at an existing building, inside Central Park. Almost immediately, that building provided insufficient, and a new site across the street from the park spanning four city blocks was purchased. The cornerstone for the first museum building was laid in 1974 by President Grant, and the building opened in 1877. Since then, it has been expanded repeatedly, with now 25 inter-connected buildings offering 570,000 square feet of exhibit space.

To fulfill its mission, the museum began sponsoring expeditions throughout the world, a “golden age of exploration that last[ed] from 1880-1930.” Explorers sponsored by the museum discovered the North Pole, trekked across Siberia, Mongolia and the Gobi Desert, and reached the unknown interior of African jungles. And that drive to explore continues today—during 2016, the museum sponsored 93 expeditions covering all seven continents.

The fruits of those expeditions have yielded a treasure of knowledge about our world and artifacts. The museum has the largest collection of natural history objects in the world, now well over 34 million in total. Included is the world’s most comprehensive and scientifically important collection of fossils, especially dinosaurs (one of which is exhibited in a soaring space that is the highest free-standing dinosaur skeleton in the world).

The museum was an early pioneer of anthropological research and collections. Today “natural history” might mean wild animals and plants, but when the museum began the term also meant learning about the world’s human cultures. The museum hired Franz Boas and sent him on an expedition of unparalleled scope to chronicle the culture of the native peoples of the Pacific Northwest. He was followed by Margaret Mead, who worked for the museum for most of her career while studying the people of the South Pacific and Southeast Asia—and originating the modern science of cultural anthropology.

The museum also pioneered the display of animal specimens in their natural environments—the dioramas so common today in museums. The pioneer of this display method was Carl Ackeley, who began building displays for the museum in 1913. Those displays were—and are—renowned for their ecological accuracy and their artistic mastery.

The American Museum of Natural History has remained at the forefront of science education. It continues to renovate its displays to incorporate new knowledge, technologies and interactivity. Nearly 5 million visitors pass through the exhibits annually, along with others that view traveling exhibits and participate on-line (not to mention the viewers of those night-at-the-museum movies!).

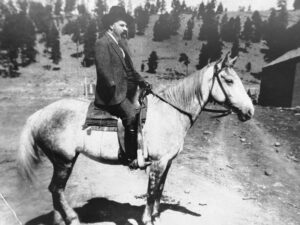

A major change to the museum is currently underway (in spring of 2022). For nearly a century, the main entrance to the museum has featured a statue showing three human figures. One is Theodore Roosevelt, riding a horse as though on a hunting expedition. The other two are standing on either side of the horse; one represents a Native American and one represents an African man. In recent years, the statue has become controversial, interpreted as showing Roosevelt dominating the other two figures, an intentional representation of racial inequality. After several years of debate and studies, the museum began removing the statue on January 18, 2022.

References:

American Museum of Natural History. 2022. Addressing the Statue. Available at: https://www.amnh.org/exhibitions/addressing-the-statue. Accessed April 6, 2022.

American Museum of Natural History. 2016 Annual Report. Available at: https://www.scribd.com/document/367739575/AMNH-Annual-Report-2016#download&from_embed. Accessed April 6, 2018.

American Museum of Natural History. History. Available at: https://www.amnh.org/about-the-museum/history. Accessed April 6, 2018.

NYC-Arts. American Museum of Natural History. Available at: https://www.nyc-arts.org/organizations/54/american-museum-of-natural-history. Accessed April 6, 2018