Education, we are all told, is most effective when it is holistic, when it emphasizes critical thinking and integration of ideas and knowledge. We treat this as a new concept, but Sombath Somphone, a Laotian educator and environmentalist, has worked according to this concept for decades.

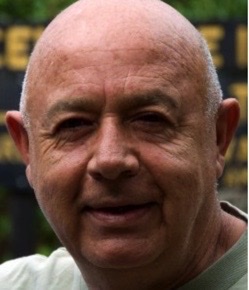

Sombath Somphone was born on February 17, 1952, in a small farming community along the Mekong River in Laos. His father began as a farmer, but soon moved on. “After I was born, my dad realized that the amount of land that grandpa had opened up to divide up among his eight siblings would not be enough to sustain his family, so that’s when he became more of a merchant.” Because his father was often away, buying or selling wares, Sombath was the man of the house.

Sombath balanced schoolwork with overseeing the family, but he was still usually the best student in class. He eventually got sent to boarding schools, where he prospered. He was known as a very serious young man. “I don’t joke around. I guess it’s a complex—being from a poor family from a rural area who went to town.”

As the French withdrew from their former colony, American teachers became more common. One took Somphone under his wing and secured an opportunity for him to go to high school in Wisconsin for the 1969-1970 academic year. That year taught him several lifelong lessons. First, he learned what it meant to be an outsider. “You are different. People look at you because you are different and you know you are different.” Second, he realized that economies and communities were also different. “Even though materially we were poor, somehow the level of our [the Laotian’s] contentment and happiness was very high. Our social security was the family. You cannot put a cash value on this.”

He returned to Laos, but soon was headed back to the U.S. on a college scholarship to the University of Hawaii. He studied agriculture, earning both Bachelors and Masters degrees. He became a leader of Asian students in 1973, but stayed out of the political conflicts that divided communist-leaning and American-leaning friends. “I didn’t want war. I wanted development.”

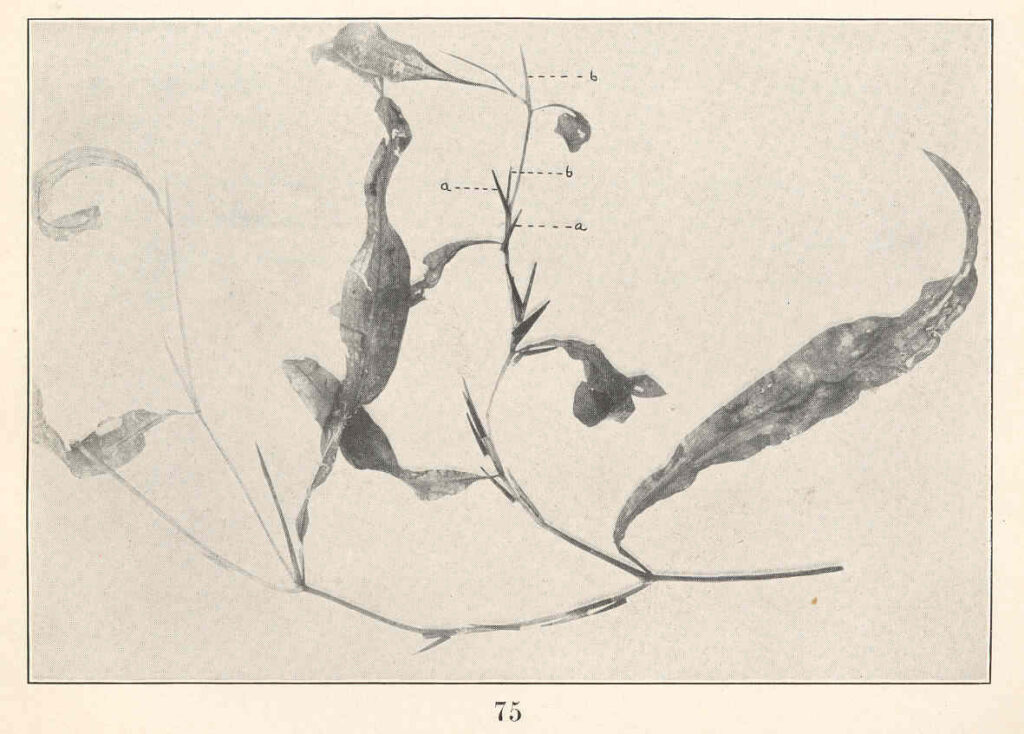

He worked in a variety of agricultural development projects across southeast Asia, scraping together resources and followers to sustain his work. His approach was not well received by conventional leaders and funders. He rejected the popularity of modern technology, instead continuing his views that integration of ideas and systems was most important. “I was going organic and chemical-free. I was again running against the current….” A tour of duty with the United Nations in Cambodia got Somphone noticed as “a competent expert,” opening the eyes of Laotian leaders. He was able to return to Laos in 1989 with funding for a new project.

Somphone created the Rice-Based Integrated Farm Systems program to implement his ideas. He was stymied by a lack of workers to join the program, so, when a new Laotian initiative allowed private schools to open, he created his own school—the Participatory Development Training Center (PADETC)—in 1996. The school developed initiatives for small rural agri-business, including using organic fertilizers, recycling, and energy efficiency. PADETC still operates today using Somphone’s ideas of collaboration and caring, rather than competition. “I’m using the word heart. Our education system doesn’t bring out the goodness of people’s hearts. They teach people to be more competitive but less caring.”

Throughout his career, Somphone raised suspicions that he was working for ulterior motives. Some thought him a CIA spy, others that he was an agent for one or another of anti-government groups. None of that was true. His interest in politics and government was only that a formal system was needed to undertake and support the sustainable development of the Laotian land and people. He received many awards for his work, including the Ramon Magsaysay Award for Community Leadership, often called the Asian Nobel Prize, in 2005. Nevertheless, he was abducted in December, 2012, after being detained by police, and has not been seen or heard from since.

In a final speech, at the Asia-Europe People’s Forum in Vientiane only a few months before his abduction, he summarized his view in words we should all heed:

“We focus too much on economic growth and ignore its negative impacts on the social, environmental, and spiritual dimensions. This unbalanced development model are the chief causes of inequality, injustice, financial meltdown, global warming, climate change, loss of bio-diversity, and even loss of our humanity and and spirituality. . . .More focus needs to be given to the protection and conservation of Laos natural resources and environment through reducing the degradation of forests, safeguarding water resources and preventing the release of toxic chemicals into land, water and air by unregulated urban and industry development.”

References:

Anonymous. Sombath Somphone. 2004. Available at: https://sombathdotorg.files.wordpress.com/2012/12/magsaysay-bio.pdf. Accessed May 7, 2021.

PADETC. Our Founder, Sombath Somphone. Available at: https://www.padetc.org/about-us/our-founder/. Accessed May 7, 2021.

Somphone, Sombath. 2012. Challenges for Poverty Reduction and Sustainable Development—A View from Laos. Asia-Europe People’s Forum, 16-19, 2012, Vientiane, Laos. Available at: https://sombathdotorg.files.wordpress.com/2012/12/keynote_speech-sombath_10_october_2012.pdf. Accessed May 7, 2021.