The world of fisheries changed forever on February 12, 1974. On that day, federal judge George Hugo Boldt issued his decision that Native Americans in the Pacific Northwest owned half the salmon in the rivers. But that was only half the story.

Native Americans have fished for salmon species in the Pacific Northwest throughout their existence. The runs of salmon from the ocean up the streams and rivers provided the sustenance that kept Native Americans well fed year round and later provided a crop that could be sold. Sites and methods for fishing and traditions surrounding the fishing were handed down from generation to generation.

When the United States began to colonize the region, the government decided that treaties were needed that made the theft of Indian lands legal. On Christmas Day, 1853, the new governor of the Washington Territory, Isaac Stevens, signed his first treaty with three Indian groups. The Indians ceded most of their land, but they retained one very important right: “The right of taking fish, at all usual and accustomed grounds and stations….”

For the next century, that treaty right was not a problem. Indians fished where, when and how they wished; the rest of the community, both commercial and recreational fishermen, did the same. But after WW2, salmon stocks began to suffer. With large dams that blocked spawning grounds, heavy logging that warmed the water and clogged streams with sediment, and greatly expanded recreational and commercial fishing, the entire fishery was in trouble. Someone needed to be blamed—and Native American fishing became the target.

The State of Washington began harassing Indian fishermen, under the premise that they had to follow the state’s fishing regulations, just like everyone else. Native American fishermen began to protest, including Billy Frank Jr. He became a central figure in the fight to assert the Indian treaty rights. He was arrested first when he was 14 and then more than 50 times for doing what he claimed was his legal right.

Clashes between conservation officers and Indians grew, increasingly attracting outside attention in the civil disobedience era of the late 1960s. At one encounter in September, 1970, violence erupted, shots were fired, and a bridge was burned. A federal attorney witnessed the event and decided he had seen enough. He sued the state of Washington for abridging the rights of the Native Americans.

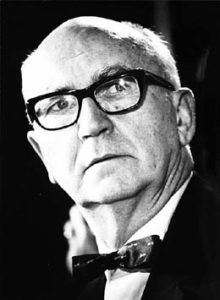

Judge George Hugo Boldt was assigned the case. The deliberations lasted until February 12, 1974, when Boldt issued his ruling. Yes, he said, the Native Americans had a right to fish where, when and how they wished. No, they didn’t own the 5% of the total catch that they were taking at the time; they owned 50% of the catch. And—most importantly for the future of fisheries management—they shared co-equal responsibility and authority for managing the anadromous fish populations of the Pacific Northwest.

The State of Washington and its supporters went ballistic. They burned Judge Boldt in effigy. They refused to back off their enforcement. They counter-sued, raising the issue to the U.S. Supreme Court. The Supreme Court affirmed Boldt’s decision in its entirety, and the state finally accepted that this was their new reality.

The affirmation of fishing rights and the assignment of half the catch to Native Americans are both important, but the other part of the decision—that Native Americans and the states had co-management responsibility—is what changed fisheries management. Now, the two groups needed to decide together, transparently, how to manage the fish populations. To do that, they needed to know a lot more about the fish—how many were present, how abundance varied annually, how many could be harvested sustainably. The age of intensive study of population dynamics began. Today, because of the Boldt Decision, the Pacific Northwest salmon fisheries are the most studied and monitored in the world. What they have learned is the basis for most fisheries management theory and practice since.

As a consequence, salmon stocks are recovering and the fisheries continue to serve the needs of Native American fishermen and communities, commercial fisheries and recreational angler. They even leave a few for the bears!

References:

Crowley, Wald and David Wilma. 2003. Federal Judge George Boldt issues historic ruling affirming Native American treaty fishing rights on February 12, 1974. HistoryLink.org Essay 5282. Available at: http://www.historylink.org/File/5282. Accessed February 7, 2018.

Nielsen, Larry A. 2017. Nature’s Allies—8 Conservationists Who Changed Our World. Island Press, Washington, DC. 252 pages.

Tizon, Alex. 1999. The Boldt Decision at 25 – The Fish Tale That Changed History. The Seattle Times, February 7, 1999. Available at: http://community.seattletimes.nwsource.com/archive/?date=19990207&slug=2943039.