Many children revolt in the shadow of a famous and demanding father. Alexander Agassiz, however, the son of world renowned scientist Louis Agassiz, did quite the opposite. He followed in his father’s large footsteps, complementing his father’s scientific creativity with a dogged determination and organizational ability.

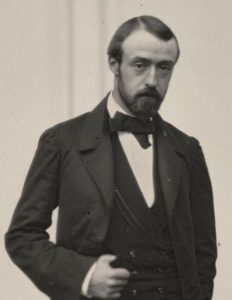

Alexander Agassiz was born in Neuchatel, Switzerland, on December 17, 1835 (died 1910). He lived there with his famous father and artistic mother, enjoying the natural environment and the intellectual stimulation. His father was “bigger than life,” as the saying goes, both in physical stature and presence—he commanded every room he entered. Alexander, in contrast, was slight of build and quiet, more given to the detail of his work than its promotion. For example, he became skilled at dissection, preparing detailed and tidy specimens for scientific observation. Nonetheless, Alexander grew to become a man of strength, courage and determination.

When his mother died at an early age, Alexander began a life of revolving stays with relatives in the Freiburg region of Germany. There he gained the idea that he would become a natural scientist. He often disappeared for days at a time, sleeping in barns or on haystacks, saying, “Almost anybody would give such a tiny traveler a piece of bread or a bit of cheese.”

He moved to the U.S. in 1849 to stay with his father who had taken a job at Harvard. Alexander, who was fluent in French and German, quickly learned English—his grammar was meticulous and his writing clear, but he sometimes spoke haltingly. Regardless, he earned several degrees from Harvard. He worked side-by-side with his father, helping him establish and grow Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology (which also covered botany, geology and anthropology). He learned that his father could raise money well, but could spend it even better, always leaving the museum—and the family—cash-strapped.

Consequently, Alexander accepted a role with a Houghton, Michigan, copper mine with which his family was connected. He quickly learned that the mine itself was a great resource, but was being squandered by the company’s poor management. Within a three-year stay, from 1866 to 1869, he developed the mine into a highly profitable enterprise equipped with the newest technology, along with innovative mine safety and worker and community welfare programs. The mine became the world’s largest copper producer. He remained president of the mining company until his death, but with his family’s money problems solved, he happily returned full-time to Harvard and science.

Soon thereafter, two sorrows tainted his life—both his beloved father and his beloved wife died within a few weeks in 1873. He devoted his life and career to their memories. He never remarried, but remained with Harvard University for the rest of his life, helping to organize, administer and expand the museum.

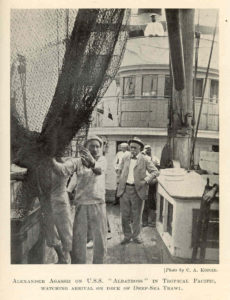

He also devoted himself to his scientific work, especially his interest in oceanography. Until his death in 1910, he conducted numerous large-scale expeditions among all the world’s oceans. Characteristically, his voyages were carefully planned and plotted to survey the largest possible regions efficiently. He invented new equipment (marine dredges), collected thousands of species and mapped huge areas of the ocean floor. He focused his biological studies on echinoderms, producing a major revision of their taxonomy. His bibliography occupies 8 pages. At the time of his death, a colleague said that all current knowledge of “the great ocean basins and their general outlines” owed itself to Agassiz, either directly or through his inspiration of other researchers.

His father was a founder of the National Academy of Sciences, and Alexander revered the institution, serving as president from 1901 to 1907. An extensive tribute to him, published by the academy, begins this way:

“An exhaustive memoir of Alexander Agassiz should consider his achievements in three distinct fields, namely, mining engineering and administration, oceanographic research, and zoological investigation. His power of mental concentration and his economy of time enabled him to accomplish results which might fairly be regarded as full measure of activity for three men.”

References:

Goodale, George Lincoln. 1912. Alexander Agassiz, 1835-1910. National Academy of Sciences, September 1912. Available at: http://www.nasonline.org/publications/biographical-memoirs/memoir-pdfs/agassiz-alexander.pdf. Accessed December 3, 2018.

Smithsonian Institution Archives. Alexander Agassiz (photograph and accompanying text). Available at: https://siarchives.si.edu/collections/siris_sic_11390. Accessed December 3, 2018.

Snow, Richard F. 1983. Alexander Agassiz: A Reluctant Millionaire. American Heritage, Volume 34, Issue 3. Available at: https://www.americanheritage.com/content/alexander-agassiz-reluctant-millionaire. Accessed December 3, 2018.