For much of history, insects were considered “beasts of the devil” and therefore were not studied. This began to change in the 1600s, when a few conscientious observers of nature decided to turn their attention to insects. One of the first—and foremost—was a German woman, Maria Sibylla Merian.

Merian was born on April 2, 1647, in Frankfurt, Germany (died 1717). Her father was a famous engraver who died when she was three. Her mother remarried, this time to the equally famous painter Jacob Marrel. Marrel painted still-lifes, and the young Merian collected specimens, both plants and insects, as subjects for his work. She fell in love with nature, particularly insects. She wrote that she “spent my time investigating insects. At the beginning, I started with silk worms in my home town of Frankfurt. I realized that other caterpillars produced beautiful butterflies or moths, and that silkworms did the same. This led me to collect all the caterpillars I could find in order to see how they changed.”

Under her step-father’s tutelage, she learned to draw and paint as both a scientist and artist. Her preferred medium was watercolor, standard for women at the time. She painted plants at first, publishing her first “Book of Flowers “in 1675, at the age of 28; two more volumes followed in rapid succession. She included insects in many of her botanical paintings, as addition decoration.

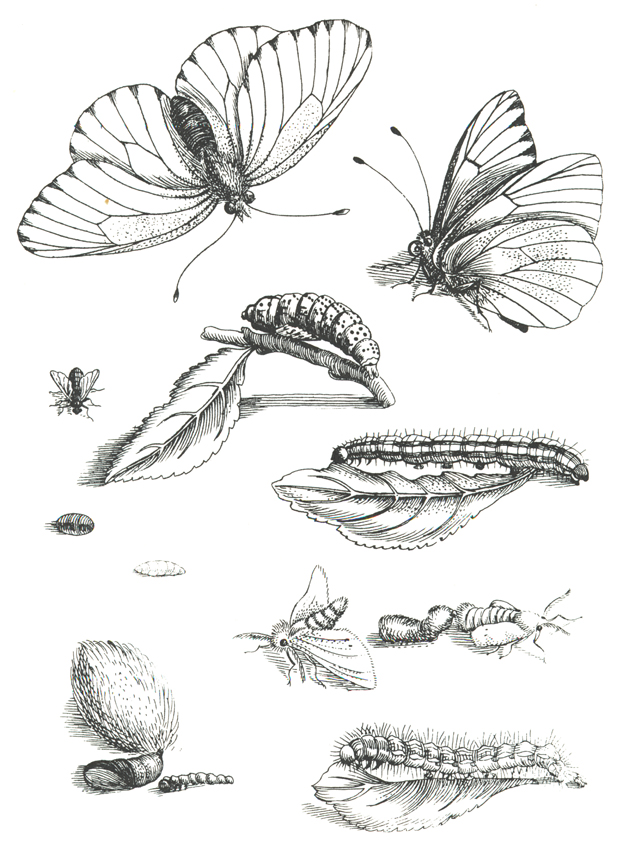

But soon she switched the nature of her compositions to emphasize insects. Through her careful field observations, she had learned that caterpillars went through various stages—from egg to pupae to butterflies or moths. She drew all the life stages of a species in one painting, adding in the plants upon which each life stage depended. The results were not only artistically compelling, but they presented a new scientific perspective on the lives of insects. Before Merian’s works were published, insects were thought to arise from spontaneous creation, out of the soil. Her books on caterpillars, which were first published in 1678, dispelled that notion.

Merian had moved to Amsterdam with her husband and two daughters, and she become intrigued with the news of expeditions returning from the Dutch colony of Suriname in South America. She viewed many collections, noting that “in these collections I had found innumerable other insects, but finally if here their origin and their reproduction is unknown, it begs the question as to how they transform, starting from caterpillars and chrysalises and so on. All this has, at the same time, led me to undertake a long dreamed of journey to Suriname.”

With the sponsorship of the Amsterdam city government, she and her younger daughter, also an artist, embarked in 1699 on a planned five-year expedition to Suriname. They collected, observed and drew plants and insects across the region. She eventually painted 60 species of insects, following their life histories from stage to stage. She also took up the cause of treatment of natives and slaves, complaining that they were abused by Dutch plantation owners. Merian contracted malaria in 1701 and had to return to Amsterdam after just two years.

In 1705, she published a book entitled “The Metamorphosis of the Insects of Suriname.” This work was the most important of her career. As one of the first illustrated accounts of the natural history of Suriname, it greatly advanced the knowledge of New World insects and plants. She became famous among both artists and scientists for the beauty and technical accuracy of her work. After her death in 1717, the Tsar of Russia, Peter I, purchased all her drawings, plates and printed works. They remain today as part of the Hermitage’s art inventory.

Merian holds a place among the most important naturalists of the 18th Century. Throughout her life, she described and painted the life cycles of 186 insects and published many scientific books. The value of her work has been re-emphasized in recent years, in connection with public recognition of the 300th anniversary of her publications and here 1717 death. She has been featured on German currency and stamps, and a oceanographic research ship is named after her.

References:

History of Scientific Women. Anna Maria Sibylla Merian. Available at: https://scientificwomen.net/women/merian-anna_maria_sibylla-67. Accessed April 2, 2019.

National Library of The Netherlands. Maria Sibylla Merian. Available at: http://www.sibyllamerian.com/biography.html. Accessed April 2, 2019

Rogers, Kara. 2019. Maria Sibylla Merian. Encyclopedia Britannica, Mar 29, 2019. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Maria-Sibylla-Merian. Accessed April 2, 2019.