Remember the adage that “if we see farther, it is because of the giants on whose shoulders we stand?” Today’s entry is about a man for whom that saying could have been written, at least for the broad fields of agriculture, conservation and natural resources.

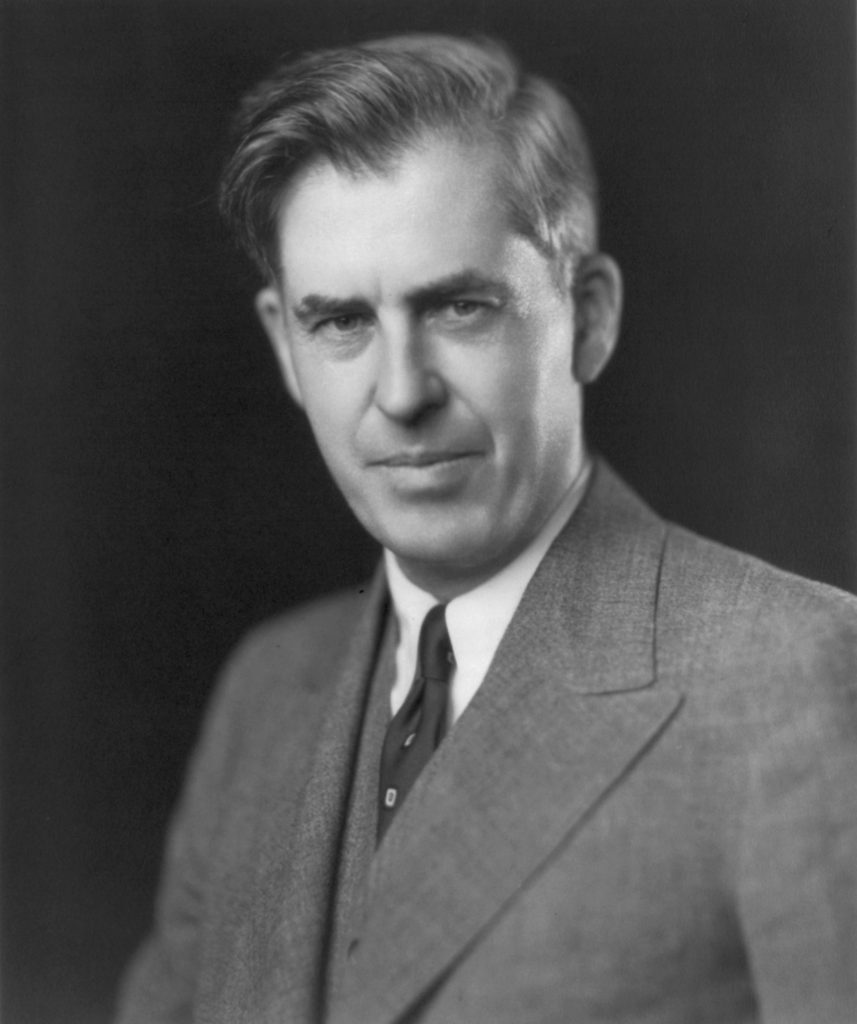

Henry Agard Wallace was born on October 7, 1888 (died 1965) on a farm in Orient, Iowa. Iowa is the birthplace of several great conservationists, but more about that later. The Wallace family was an agricultural dynasty. Both his father and grandfather played large roles in the development of modern agriculture, through crop breeding, publishing, and public service. The young Wallace did the same. He learned about crop breeding from George Washington Carver, the African-American innovator of peanut crops and products, who lived with the Wallace family. Wallace went to Iowa State, where his father taught agriculture, and both father and son helped establish several new agricultural science programs over the years. When his father went to Washington as President Coolidge’s Secretary of Agriculture, the younger Wallace took over editing the family’s farm journal, Wallace’s Farmer.

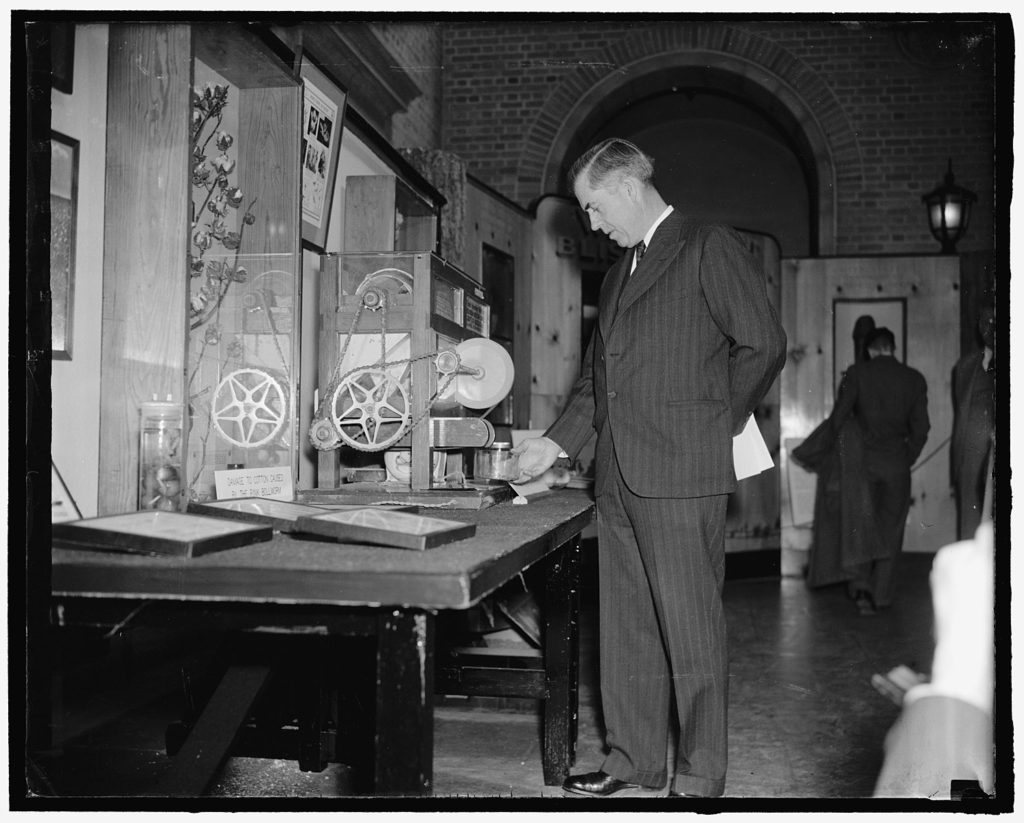

Wallace was an even better crop breeder than his father. He developed the first commercial hybrid corn variety to be marketed widely in the U.S., a product that laid the foundation for his company, Pioneer Hi-Bred, once the largest seed-corn producer in the world Later, he had similar success with hybrid egg-laying chickens (you might have eaten an egg from one of his company’s chickens this morning at breakfast).

Wallace grew up a Republican, but he became disillusioned with Republican farm policies during the Great Depression. He became a Democrat and served as an agricultural advisor to presidential candidate Franklin Roosevelt. When Roosevelt was first elected in 1933, he brought Wallace to Washington as his Secretary of Agriculture. Wallace kept that job for eight years, before becoming Roosevelt’s vice-president in 1941.

Most biographies focus on Wallace’s years as vice-president (a checkered outcome), but his role as Secretary of Agriculture is our interest. Wallace believed that the world of commerce, agricultural and beyond, needed to be regulated by government so that it did not destroy the very basis on which it depended—that is, natural resources. He expressed his viewpoint in 1936: “Probably the most damaging indictment that can be made of the capitalistic system is the way in which its emphasis on unfettered individualism results in exploitation of natural resources in a manner to destroy the physical foundations of national longevity.”

That philosophy made him a friend of two of Iowa’s most prominent conservationists, Ding Darling and Aldo Leopold. When it became clear to Wallace that the Bureau of the Biological Survey (now the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) was in desperate need of reorganization, he convinced President Roosevelt to bring in Darling and Leopold (and one other person) to do the work. A short time later, he talked the president into giving Ding Darling the task of implementing the recommendations as Chief of the Survey. In less than two years, Darling reformed the agency, expanding its infant National Wildlife Refuge System into the essential habitat protection agency that we know today.

Aldo Leopold never went to Washington, but returned to his job as the first professor of wildlife science in the U.S., at the University of Wisconsin. Leopold is known widely as the father of wildlife management and even more widely as author of modern conservation’s ethos in his book, Sand County Almanac.

Wallace also believed that the future of the world depended not just on U.S. success, but on improving the condition of all people throughout the globe. He spoke about the “common man,” meaning not just the average American, but also the poor and needy around the world (so moving were Wallace’s exhortations to work for all that he inspired Aaron Copeland to compose his famous piece, Fanfare for the Common Man).

Part of Wallace’s vision included breeding crops that could relieve famine across throughout the tropics. His message inspired another crop breeder (and, I would argue, great environmentalist) from Iowa, Norman Borlaug. Borlaug went to Mexico where he bred hybrid wheat and other crops, leading what has become known as the Green Revolution. As the techniques of the Green Revolution spread from one country and region to others, Borlaug was credited with saving 1 billion human lives.

Henry Wallace came in for much criticism during his public service career. He was idealistic, often given to causes (for example, communism and spiritual mysticism) that he later regretted. Equipped with integrity and a strong moral compass, he made a poor politician and deal-maker. He spoke strongly in favor of re-distributing wealth and power, even as an exploding economy seemed to be “lifting all boats.”

But what he lacked in charisma and popularity he made up for in other ways. Most importantly for conservation, he understood that money wasn’t everything. The human condition and the condition of our natural resources were more important. And let some great people stand on his shoulders.

References:

Nielsen, Larry A. 2017. Nature’s Allies: 8 Conservationists Who Changed Our World. Island Press, 255 pages.

Ross, Alex. 2013. Uncommon Man; The strange life of Henry Wallace, the New Deal visionary. The New Yorker, October 7, 2013. Available at: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2013/10/14/uncommon-man. Accessed August 21, 2019.

United States Senate. Henry Agard Wallace, 33rd Vice President (1941-1945). Available at: https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/generic/VP_Henry_Wallace.htm. Accessed August 21, 2019.

Wallace Global Fund. Henry A. Wallace. Available at: http://wgf.org/henry-wallace/. Accessed August 21, 2019.