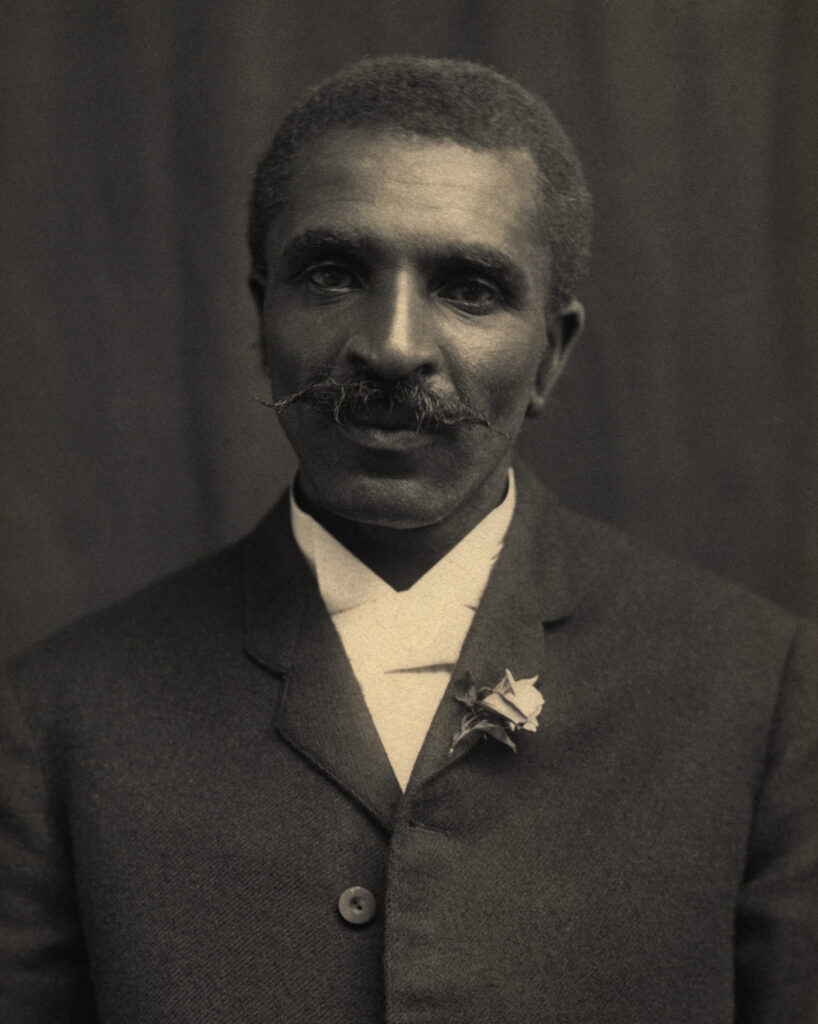

The founding of this national monument provides an opportunity to discuss the life and accomplishments of George Washington Carver, pioneering African-American plant scientist and conservationist.

Carver was born during the Civil War, but the date is unknown—because he was a slave. He and his family lived and worked on the farm of Moses Carver (hence, his last name), a Missouri farm that grew mostly cotton. After slavery was abolished, Carver continued to live on the farm for several years. The Moses family cared for the sickly boy, never expecting him to live past his teen years. Carver later wrote, “…my body was very feble and it was a constant warfare between life and death to see who would gain the mastery.”

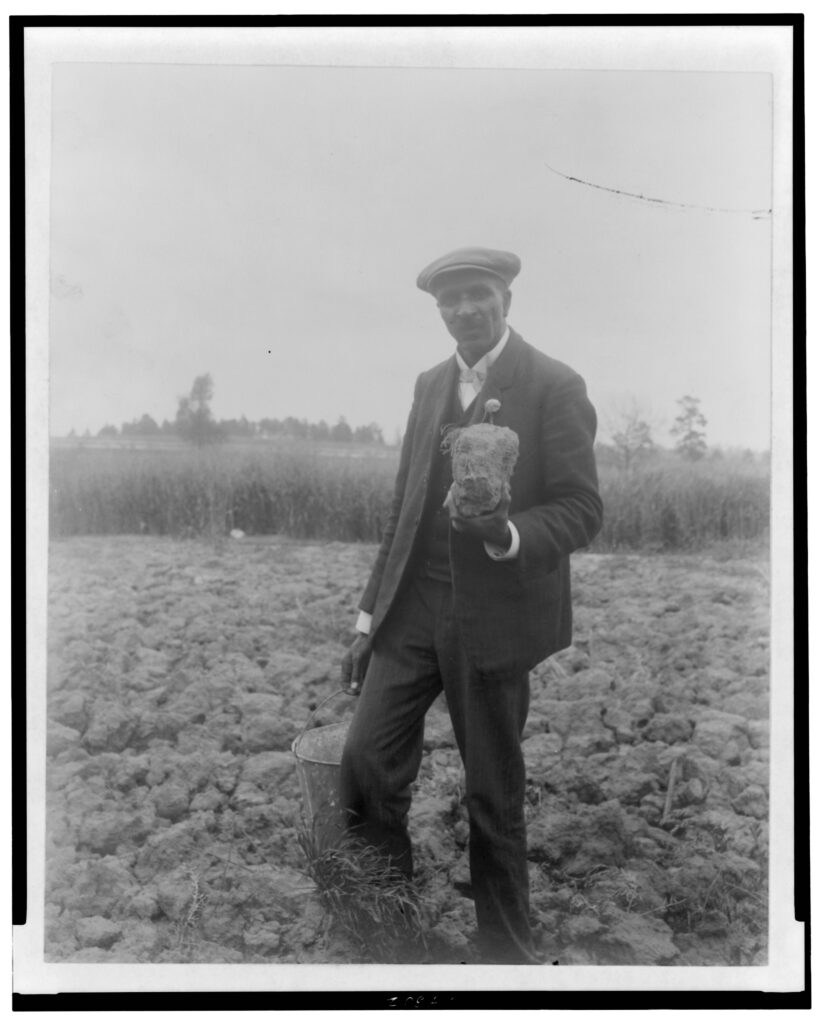

The young Carver reveled in nature. “Day after day,” he said, “I spent in the woods alone in order to callect my floral beauties…” He had the proverbial green thumb, musing that “strange to say all sorts of vegetation seemed to thrive under my touch until I was styled the plant doctor…. At this time I had never heard of botany and could scerly read.”

He did learn to read. For two decades, he roamed around Missouri, Kansas and Iowa, earning a living however he could and attending whatever school was nearby. He eventually landed at what is now Iowa State University, graduating with both B.S. and M.S. degrees in agricultural sciences in his 30s. He served as an agricultural teacher there before heading to the Tuskegee Institute in 1896.

At Tuskegee, he led the new agriculture program and developed the innovations for which he is famous. Realizing that more than a century of cotton farming had depleted the Alabama soils, Carver taught farmers to plant soil-nourishing crops of peanuts and soybeans. He performed research on the university’s experimental farm, developing more than 300 products from peanuts and 100 from sweet potatoes, basically establishing both plants as the major crops they are today. He designed and built the “Jessup Wagon,” a mobile classroom that he took around Alabama to demonstrate new techniques and crops to farmers. To accompany his tours, he wrote simple booklets for farmers, the precursor of today’s “extension bulletins.” He taught methods to reduce soil erosion and improve soil productivity, rejuvenating southern agriculture.

Carter was a humble and spiritual man. His critics saw him as capitulating to white dominance in the South, but Carter cared nothing for politics and strife. As Tuskegee describes him, “Always modest about his success, he saw himself as a vehicle through which nature, God and the natural bounty of the land could be better understood and appreciated for the good of all people.” He is considered one of America’s greatest agricultural leaders, and when he died in 1943, it took only months for the U.S. to create a national monument of his birthplace.

The monument itself is noteworthy. It encompasses the entire 240-acre Moses farm in the far southwestern corner of Missouri. It was the first birthplace memorial in the National Park Service not honoring a U.S. president. And it was the first national park unit to celebrate the life of an African-American. The congressional hearings to establish the monument included this homage to Carver:

“Occasionally there moves across the stage of time a historic figure, a creative teacher, a profound thinker, a humble servant, or an inspiring teacher. George Washington Carver was all of these. The memorial we create only indicates to the world that once there was a man named George Washington Carver, whose life was a source of inspiration to all men, a pillar of hope to his race, a fountain of service to his fellows, a tower of devotion to his God; and that this man achieved a worthy and enduring stature in the memories of men.”

Amen to that.

References:

Encyclopedia Britannica. George Washington Carver. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/biography/George-Washington-Carver. Accessed March 25, 2020.

National Park Service. George Washington Carver National Monument. Available at: https://www.nps.gov/places/george-washington-carver-national-monument.htm. Accessed March 25, 2020.

National Park Service. George Washington Carver National Monument, History & Culture. Available at: https://www.nps.gov/gwca/learn/historyculture/index.htm. Accessed March 25, 2020.

Tuskegee Institute. The Legacy of Dr. George Washington Carver. Available at: https://www.tuskegee.edu/support-tu/george-washington-carver. Accessed March 25, 2020.

Williams, Wendi. 2020. The Jessup Wagon: Rooted in History, Still Used Today. Alabama Cooperative Extension Service, February 6, 2020. Available at: https://www.aces.edu/blog/topics/news/the-jesup-wagon-rooted-in-history-still-used-today/. Accessed March 25, 2020.