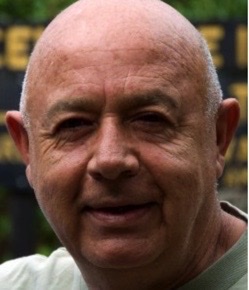

Costa Rica is famous for its commitment to conservation and sustainability. The country has more of its land and waters in protected parks and other reserves (about 27%) than any other nation in the world. And much of that success can be traced to Alvaro Ugalde, known as the father of Costa Rica’s national parks.

Ugalde was born in Heredia, Costa Rica, a mountain village, on February 16, 1946 (died 2015). He had an early love of nature and pursued that love to get his first college degree in biology from the University of Costa Rica in 1970. Later, he studied at the University of Michigan, earning an M.S. in Natural Resource Management (1973).

Costa Rica’s first national park, Santa Rosa had been established in 1970, through the urging of Mario Boza, who would work with Ugalde for decades in their campaign for conservation (Mario Boza is rightfully credited as the co-father of the country’s national parks). “Even before I finished my BS in Costa Rica,” Ugalde said, “I was already a volunteer in the first national park, which existed but had no staff, no management. So I decided to start volunteering there…”. He volunteered patiently, until he was finally put on the payroll as the park’s first director.

In 1974, Ugalde became director of the country’s national parks when Boza, who had held the position, resigned to move to an academic position. That began Ugalde’s 17 years at the helm, building the system into the success we know it as today. He worked closely with a succession of presidents, effectively convincing one after the other that conservation and ecotourism would be good for the country. Part of his success was “because some of the parks that we started with—actually most of the park system, were ecosystems that were still pretty much left out by the agricultural development, either because they were very steep mountains like all our mountains, especially the top part of them, or because they were swamps, beautiful wetlands of course but swamps nonetheless for agriculture and just by luck maybe, lack of action, something like that.” Park after park was added to the system, which now includes 29 national parks and many more other forms of protected areas.

Ugalde left the government in 1991 and spent a decade working with the United Nations and other conservation organizations. In 1999, he co-founded the Nectandra Institute, which works to conserve the cloud forests of Costa Rica; he served as president until his death in 2015. He was also active in the Osa Foundation, an organization committed to the preservation of the Osa peninsula on the south coast of Costa Rica. Over his life, Ugalde earned many awards for conservation, within Costa Rica, throughout the Americas, and, indeed, throughout the world.

Ugalde was particularly interested in the Osa Peninsula, which contains Corcovado National Park. The park is the largest in Costa Rica, occupying a large portion of this region rich in biodiversity (purported to contain 2.5% of the world’s biodiversity). “Osa is as one of the most magnificent places on the planet,” he said, “a place that later, through my actions, would become Corcovado National Park, a place for which I am still fighting for almost 40 years later.”

Ugalde well understood that environment and development must co-exist for sustainability, recognizing the importance of natural capital as the basis for human society. He wrote the following:

“Costa Rica’s national parks and other protected areas, not only help protect more than 4% of earth’s biodiversity, in a tiny country that is largely invisible on a world map, but also played a pivotal role in restoring forest cover back to near half of Costa Rica’s land area, after falling to a low of approximately 1/5 in the 80s. These parks also set the stage for what is today perhaps our top money maker: the tourism industry. It turned out to be an excellent investment in our natural capital.

Furthermore, the national parks system, together with other lands that are under the ownership and protection of local communities, non-profit organizations and private individuals, have helped maintain vital services the Planet provides us, services we notoriously take for granted, such as the provision of drinking water and the “hidden water” contained in virtually all our goods and services, soil erosion control, flood mitigation, carbon sinking and climate moderation. “

References:

Boza, Mario. 2015. M.Sc.Álvaro F. Ugalde Viquez. Bi ocenosis 30(1-2):2-4.

Cahn, Robert and Patricia. 1979. Treasure of parks for a little country that really tries. Smithsonian 10(6):64-73. Available at: https://www.cartermuseum.org/collection/treasure-parks-little-country-really-tries-robert-and-patricia-cahn-nd. Accessed February 23, 2021.

Camerson, Blair. 2015. Interview of Alvaro Ugalde for Innovations for Successful Societies, Princeton University. Available at: https://successfulsocieties.princeton.edu/sites/successfulsocieties/files/interviews/transcripts/3917/D2%20FT%20BC%20Alvaro%20Ugalde_Final.pdf. Accessed February 23, 2021.

Osa Conservation. Available at: https://osaconservation.org. Accessed February 23, 2021f

Ugalde, Alvaro. In Alvaro’s Words. Nectandra Institute. Available at: https://www.nectandra.org/retro/article.php?name=NaturalCapital. Accessed February 23, 2012.