Cruelty to animals is considered a sin in modern society, but in the 1800s, cruelty was commonplace. Henry Bergh, a rich socialite with a profound sense of what it means to be humane, changed all that.

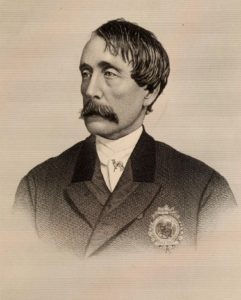

Henry Bergh was born on August 29, 1813 (died 1888). The term “born with a silver spoon in his mouth” could have been coined to describe Bergh. His father was a wealthy shipbuilder in New York City, but considered an honest, fair and responsible man. His mother was equally gentle and considerate. Henry inherited those qualities from his parents, along with a considerable fortune.

Bergh and his brother took over the family business and ran it successfully for several years before selling out and becoming men of leisure. Bergh and his wife were “first night” socialites, generally appearing at the openings of plays, musical events and art exhibits in New York. The Berghs traveled often to Europe, enjoying the best of life. He loved the theater especially, and fashioned himself as a playright. He wrote several plays, and convinced friends to stage them—all were dismal failures.

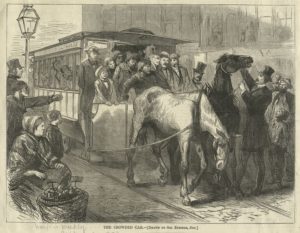

Because of his wealth and political connections, Bergh received a diplomatic posting from President Lincoln, serving in St. Petersburg, Russia. While there, he experienced frightful treatment of animals, particularly work horses. Once he observed a draft horse being whipped, he jumped from his carriage and confronted the horse’s owner. That day, we are told, convinced Bergh that preventing cruelty to animals was his life’s work. He resigned his diplomatic post and sailed back to New York. On the way, he stopped in England to consult with the nation’s leading anti-cruelty advocate.

Back in New York, Bergh promoted his anti-cruelty message with passion and perseverence. Animals should not be treated as property, he asserted, but as fellow creatures with whom we shared the earth. “This is a matter purely of conscience,” he wrote, “it has no perplexing side issues. It is a moral question in all its aspects.” Although he couldn’t write plays, he could write provocative and persuasive letters to newspapers, politicians and rich patrons. He soon convinced the state of New York to issue him authority to form the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA), founded in 1866.

Within two weeks, the New York legislature passed an anti-cruelty law and put the ASPCA in charge of enforcing the new law. Bergh went to work with a staff of officers. He roamed the streets of New York, often in the worst neighborhoods and in the dark of night. With the new law in his pocket, he accosted anyone seen mistreating an animal. If a simple lecture did not deter the offender, Bergh would drag him from his seat to demonstrate his authority and courage. He went after the treatment of work animals first, but also challenged dog-fighting and cock-fighting and the mistreatment of domestic animals. He created the first ambulances, for transporting sick and injured horses to veterinarians—his horse ambulances were the model for their later use for humans!

Bergh received both praise and criticism for his efforts. His supporters called him “An Angel in Top Hat.” His detractors called him “The Great Meddler.” He withstood death threats and physical beatings. He clashed with P. T. Barnum over the treatment of circus animals, carrying out a high-profile public debate. In the end, Bergh won over Barnum, who changed his practices.

And, in the end, of course, he has convinced modern society to treat animals humanely. His founded the first anti-cruelty organization in the U.S., with many thousands of similar groups now working effectively across this country and the world.

And how does this relate to conservation? The expansion of ethical treatment from people to domesticated animals is an essential step on the road to the protection of wild creatures, then wild places and, finally to a sustainable earth. Organizations that protest the inhumane treatment of animals work side-by-side with more direct conservation organizations to help people understand that all of creation needs our help—and we will perish without the rest of creation. “Mercy to animals,” Bergh wrote, “means mercy to mankind.”

References:

ASPCA. History of the ASPCA. Available at: https://www.aspca.org/about-us/history-of-the-aspca. Accessed July 10, 2018.

Ferguson, Mark. 2007. Henry Bergh. Dictionary of Unitarian & Universalist Biography, April 22, 2007. Available at: http://uudb.org/articles/henrybergh.html. Accessed July 10, 2018.

O’Reilly, Edward. 2012. Henry Bergh: Angel in Top Hat or the Great Meddler? New York Historical Society, March 21, 2012. Available at: http://blog.nyhistory.org/henry-bergh-angel-in-top-hat-or-the-great-meddler/. Accessed July 10, 2018.

Zawikowski, Stephen. Bergh, Henry. Learning to Give.org. Available at: https://www.learningtogive.org/resources/bergh-henry. Accessed July 10, 2108.