Imagine a combination of John Muir and Mark Twain, one an astute observer of nature and the other a journalist of his worldwide travels. Both were enormously popular during their lives—and both are still popular today. Now, imagine them as a British woman doing the same things at about the same time—and you have Isabella Bird.

Isabella Bird was born in Yorkshire, England on October 15, 1831 (died 1904). The daughter of a clergyman and his wife, Bird was a proper young English woman in all ways. She was a sickly child and young adult, however, plagued especially by back troubles. Doctors recommended that she travel for her health, so her father gave her 100 English pounds and told her to go wherever she wished.

And did she ever go! For the rest of her life, she traveled and traveled and traveled. It is said that when she died, her bags were packed for her next planned expedition. Unlike other well-bred Europeans of the time, however, she set her course for the wilderness, wherever she could find it. Her first trip was to the western United States, where she began writing the compelling natural history that made her famous:

“This is no region for tourists and women, only for a few elk and bear hunters at times, and its unprofaned freshness gives me new life. I cannot by any words give you an idea of scenery so different from any that you or I have ever seen. This is an upland valley of grass and flowers, of glades and sloping lawns, and cherry-fringed beds of dry streams, and clumps of pines artistically placed, and mountain sides densely pine-clad, the pines breaking into fringes as they come down upon the ‘park,’ and the mountains breaking into pinnacles of bold grey rock as they pierce the blue of the sky.”

She traveled around the world, making many trips to the U.S. and Canada, but also trips to Australia (it was hot, she said, and full of flies and drunk men), New Zealand, the Middle East, China, Japan, and Korea. But it was a seven-month stop-over in Hawaii, on her way home from Australia in 1873, that changed her life. She loved Hawaii because “there are none of the social constraints of colonial rule or Victorian moral correctness.” She also loved the coral reefs, volcanic landscapes and tropical forests. She became an excellent horsewoman, learning to ride astride her horse, a position that solved her chronic back problems. She wrote intimate and informal letters home to her sister, Henrietta, and later published them as a book. The book was an instant best-seller, earning her fame and financial independence.

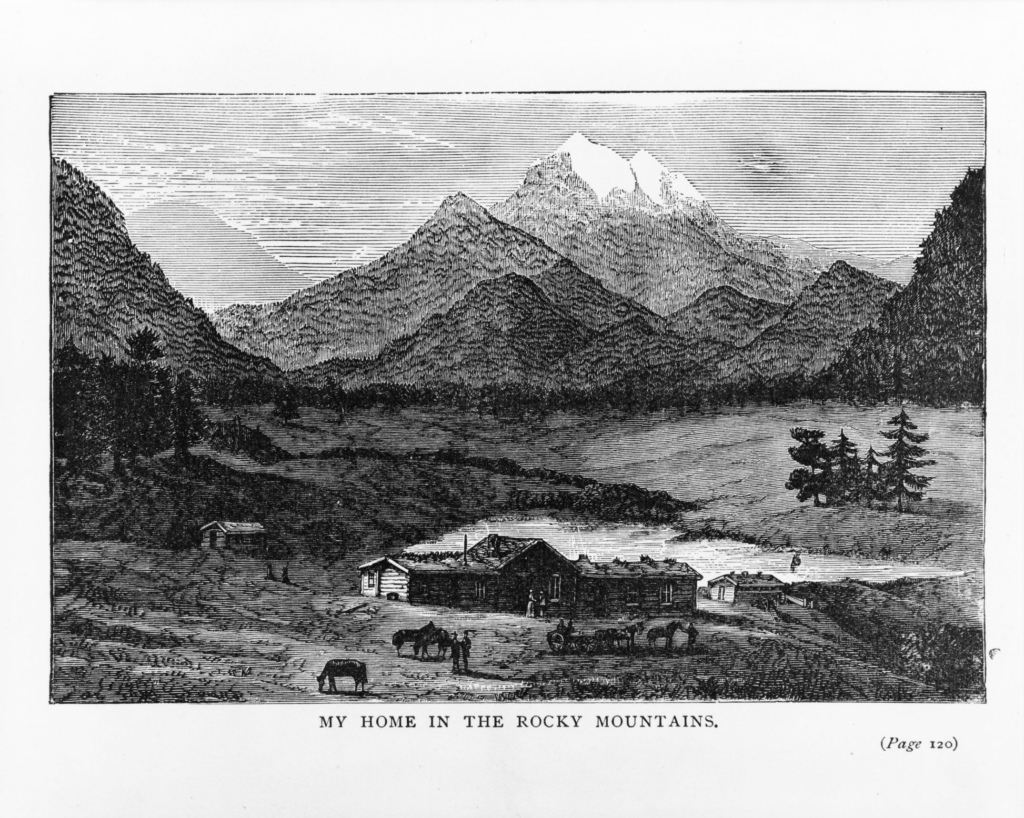

After her Hawaiian visit, she landed in California and headed east on horseback (by herself) into the Rocky Mountains. She settled for a time in Estes Park, Colorado, entranced by the scenery and the wildlife. She teamed up with a local cowboy and outlaw known as “Mountain Jim” (she described him as “a man any woman would fall in love with but who no sane woman would every marry”). Together they climbed Longs Peak, an extraordinarily difficult ascent, just a few years after the first recorded climbs. She was, as one biographer wrote, a true “outdoor bad ass.”

Her second book, published in 1879, A Lady’s Life in the Rocky Mountains, was also a best-seller. Her descriptions of the Estes Park region appealed to the educated men and women of the Eastern U.S. and Europe, eager for tales of wilderness and adventure. She wrote, “I have found a dream of beauty at which one might look all one’s life and sigh.” She was the female counterpart to John Muir, writing much as he did and about similar places. The National Park Service suggests that Bird should be called the “Mother of Rocky Mountain National Park” for bringing the area, and its need for protection, to the loving attention of the American public. Just like John Muir, she enthralled readers with the majesty of these places and the need for their conservation:

“Grandeur and sublimity, not softness, are the features of Estes Park. The glades which begin so softly are soon lost in the dark primaeval forests, with their peaks of rosy granite and their stretches of granite blocks piled and poised by nature in some mood of fury.”

References:

Encyclopedia.com. Isabella Lucy (Bird) Bishop. Available at: https://www.encyclopedia.com/people/history/british-and-irish-history-biographies/isabella-lucy-bird-bishop. Accessed September 27, 2019.

Heaver, Stuart. 2015. Isabella Bird, Victorian pioneer who changed West’s view of China. South China Morning Post, 8 Aug 2015. Available at: https://www.scmp.com/magazines/post-magazine/article/1846990/isabella-bird-victorian-pioneer-who-changed-wests-view-china. Accessed Septpember 27, 2019.

National Park Service. Isabella Bird’s 1873 Vist to Rocky Mountain National Park. Available at: https://www.nps.gov/romo/isabella_bird_visit.htm. Accessed September 27, 2019.

Ross, Tracy. 2019. Seven reasons Isabella Bird should be your new role model. Visit Estes Park, Jan 04, 2019. Available at: https://www.visitestespark.com/blog/post/seven-reasons-isabella-bird-should-be-your-new-role-model/. Accessed September 27, 2019.