In the mid-1800s, London’s Thames River was a sewer. A huge, foul, disease-causing cesspool fed by the wastes of London’s exploding human population. Something had to be done, and Joseph Bazalgette did it.

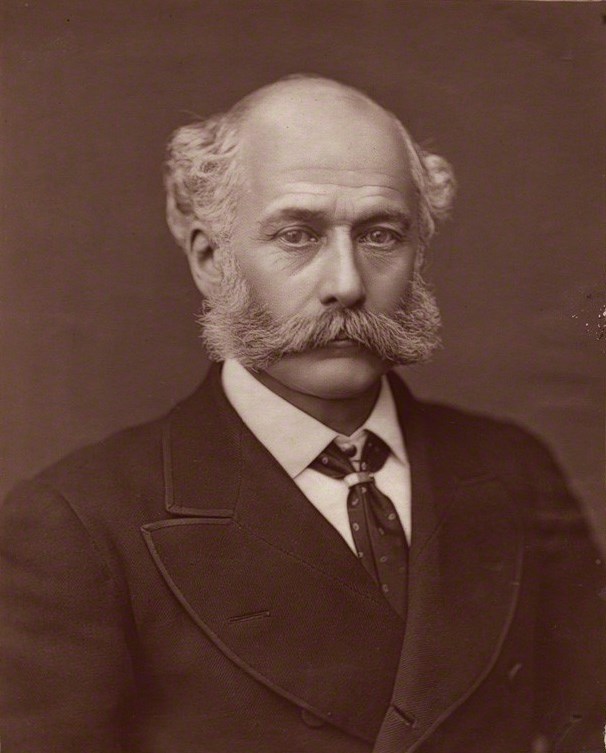

Joseph Bazalgette was born on March 28, 1819, the son of a naval engineer (died 1891). Like his father, he also became an engineer. He designed and built railroads as part of the enormous expansion of the railway system of Great Britain during the early 19th Century. Exhausted by the scale and pressure of the work, he eventually returned to London and took up work as an engineer for the newly formed Metropolitan Board of Works.

And sewers became his major task. London’s sanitary system was a mess. Mostly, human waste was just washed into small streams that flowed to the Thames River. The streams were noxious slurries that sloshed back and forth with the tides and mixed with drinking water supplies, including the Thames River itself. Because of this contamination, cholera became an epidemic in London, killing more than 30,000 people at mid-century. A particularly hot and dry summer in 1858 caused the “Great Stink”—the overwhelming putrid smell of the Thames River. In the riverside Parliament, curtains were doused in chlorine to freshen the air and prevent disease. It didn’t help, and Parliament passed legislation ordering the city’s engineers to fix it.

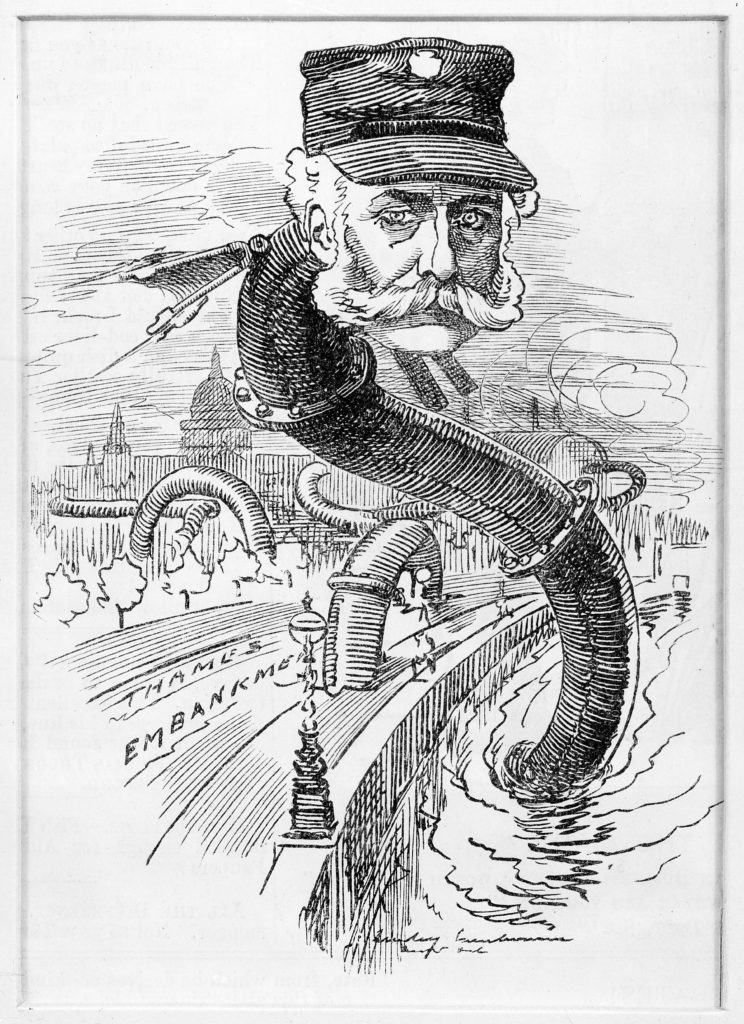

Joseph Bazalgette gladly accepted the task. He designed a series of sewers that captured the wastewater coming from homes and businesses. These sewers connected to a massive sewer that paralleled the shore of the Thames River and carried the foul water many miles downstream. To avoid digging up miles of central London, Bazalgette proposed narrowing the river and building massive “embankments” to hold the sewers and other needed facilities—including electrical and telegraph lines and underground trains. At the time, his plan was the largest civil engineering project in the world. So much for avoiding big scale and high pressure projects!

The work began in 1859 and continued for 16 years. Under Bazalgette’s leadership, the city built 1100 miles of street sewers and 82 miles of main sewers. The main sewers lie beneath the Thames, Chelsea and Albert Embankments that make up the sides of the Thames River in central London. The main sewers are three feet in diameter, in an inverted tear-drop shape. This shape allows the sewers to take massive amounts of water at high flows and still operate effectively at low flows, removing waste along the narrower bottom of the pipe.

Bazalagette’s approach was pure genius. He calculated the size of a sewer to handle all of London’s waste—and then doubled the size. To this day, his sewers continue to be the primary sanitary system for London (but a major expansion of the system is now underway). His work stopped epidemics of cholera and other water-borne diseases in London, allowing the Thames to recover as both a source of drinking water and habitat for fish and other aquatic organisms. And his riverside embankments, with sewers and train lines below and roads, paths and gardens above, are a major element of London’s vibrant urban environment.

Bazalgette was knighted by Queen Victoria and honored in other ways during his life. The only permanent memorial to him, however, is a modest bust on the wall of the Thames Embankment. The inscription reads, “Flumini vincula posvit”—“He put the river in chains.” More appropriate, I think, would be that he set the river free, free of the pollution that was killing it and us.

References:

BBC History. Joseph Bazalgette (1819-1891). Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/bazalgette_joseph.shtml. Accessed March 25, 2019.

Hansen, Chad. Sir Joseph Bazalgette. Cholera and the Thames. Available at: https://www.choleraandthethames.co.uk/cholera-in-london/the-big-thames-clean-up/sir-joseph-bagalgette/. Accessed March 25, 2019.

Londontopia. Great Londoners: Joseph Bazalgette—The man who ended the Great Stink. Available at: https://londontopia.net/columns/great-londoners/great-londoners-joseph-bazalgette-man-ended-great-stink/. Accessed March 25, 2019.