If you were looking for a poster illustration of how species go extinct, you could stop your search right here at the Great Auk. This large, flightless bird of the North Atlantic had no chance of survival as a new and lethal force entered its environment—humans.

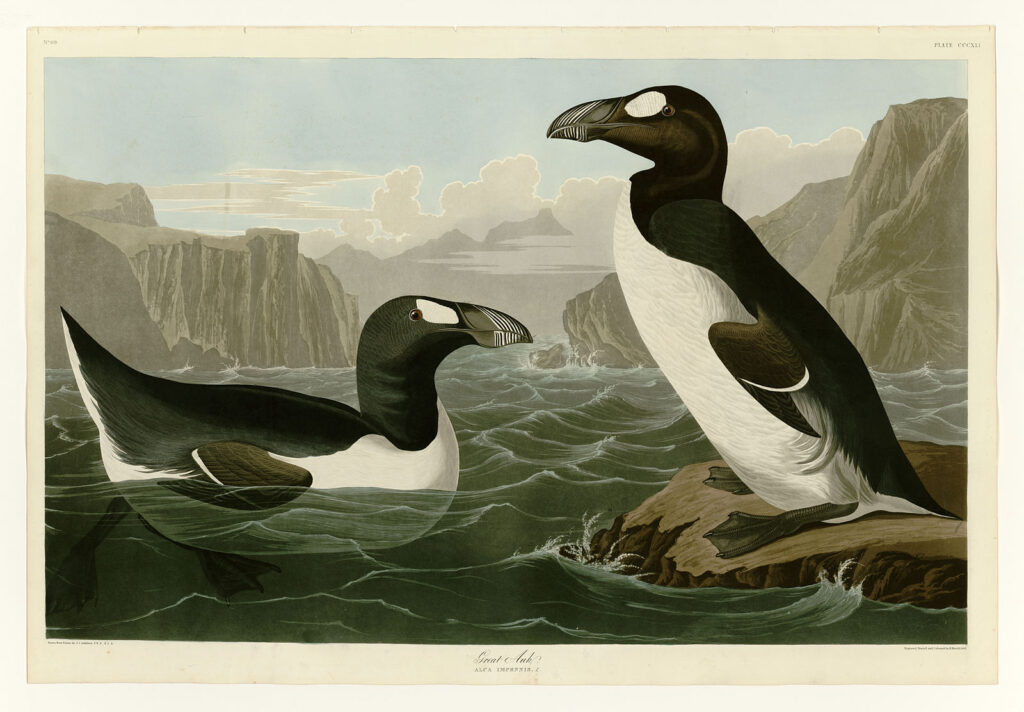

We have few details about the ecology of the Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis) , but what we do know foretells a tragic story. Early sailors called them penguins (although they aren’t), and they share several life-history traits with penguins. Great Auks evolved to be big—about 2 feet tall and weighing about 10 pounds, too big to fly. Like penguins, Great Auks were clumsy on land. But they were excellent swimmers, using their shortened wings as fins to propel them in pursuit of fish. They stayed in the water except for breeding, when they came ashore in large colonies to lay, brood and hatch a single egg per female. The colonies stretched across the North Atlantic, from the waters off Great Britain all the way around to the Canadian maritime provinces.

Great Auks numbered in the millions until the trouble began. In the last “little ice age” (circa 1500-1800), sea ice linked their breeding islands together with larger land areas. That gave polar bears access to Great Auk breeding grounds, increasing natural predation on the birds. But the big change came as fishing and sailing traffic across the North Atlantic increased. Humans quickly learned that the Great Auk was, forgive the ornithologically inaccurate pun, a sitting duck. The dense flocks on breeding islands were exploited easily; one sailor reported that the birds were so thick “that a man could not put his foot between them.” Another sailor noted that harvesting the defenseless birds was as effortless as collecting stones. The birds provided eggs and meat for sailors, bait for fishing, feathers for pillows, and even fuel—the oil-rich carcasses could be burned when other fuels ran low.

By the mid-1800s, hunting had made the birds scarce. Breeding colonies had been destroyed on many smaller islands, leaving only a few larger colonies extant. As numbers dwindled, collectors became the next threat. One specimen of an adult bird or an egg could bring $16, the equivalent then of a year’s wage for a skilled worker. About 80 specimens remain in museums and private collections today.

The last major colony of Great Auks bred on an Icleandic island called Geirfuglasker, which means “Great Auk Rock.” Nature destroyed that colony in 1830 when the island sunk after a volcanic eruption. Five years later, however, a few birds were found on nearby Eldey, a tiny island of about 10 acres. Museums and private collectors quickly targeted the island. A trio of collectors caught and killed the last pair of Great Auks on July 3, 1844. In the process, they also accidentally crushed the last egg.

( The story requires a little caveat. Sources differ on exactly when those last two birds were captured and killed. Modern websites generally agree on July 4, 1844. But older sources state that the probable date of extinction was in June, not July, and anywhere from the 2nd to the 5th. Alfred Newton, an early professor of zoology at Cambridge University and an expert on the Great Auk, interviewed the collectors some years after their return; he likes July 3rd. But, as other observers have said, sailors are not particularly good with dates—so, you pick!)

The story of the Great Auk joins with several others—the Passenger Pigeon, for example—that demonstrate what can happen when extinction’s perfect storm occurs (learn more about the Passenger Pigeon here). When a species has an innately risky life history, has great value to humans, and can’t defend itself, tragedy is the likely outcome.

References:

Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Great Auk. Available at: https://birdsna.org/Species-Account/bna/species/greauk/introduction. Accessed March 12, 2020.

Giaimo, Cara. 2019. Why the Great Auk Is Gone for Good. The New York Times, Dec. 4, 2019. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/04/science/great-auks-extinction.html. Accessed March 12, 2020.

Galasso, Samantha. 2014. When the Last of the Great Auks Died, It Was by the Crush of a Fisherman’s Boot. Smithsonian Magazine, July 10, 2014. Available at: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/with-crush-fisherman-boot-the-last-great-auks-died-180951982/. Accessed March 12, 2020.

John James Audubon Center at Mill Grove. The extinction of The Great Auk. Available at: https://johnjames.audubon.org/extinction-great-auk. Accessed March 12, 2020.

National Geographic. Jul 3, 1844 CE: Great Auks Become Extinct. Available at: https://www.nationalgeographic.org/thisday/jul3/great-auks-become-extinct/. Accessed March 12, 2020.