Let’s get one thing straight right now: Native Americans knew well before 1832 where the Mississippi River started. So, what July 13, 1832, represents is the day when someone told the world about it.

That someone was Henry Rowe Schoolcraft. Schoolcraft worked for the U.S. government, responsible for relations with Native Americans of the Upper Great Lakes Region. He married a Native-American woman, Jane Johnston, and conducted his work with sincerity and respect. He was also an explorer and writer, and he sought to investigate a doubtful claim of where the Mississippi River actually began. An Ojibwe leader named Ozawindib showed Schoolcraft to the place where the Mississippi formed a small channel draining out of a small Minnesota lake—and the rest was history.

The lake is now named Lake Itasca, and it lies within Itasca State Park in northern Minnesota. The small channel has become quite a tourist site, and it has been stabilized with a small dam covered with a row of rocks that lets visitors walk across the 20-foot-wide Mississippi (I’ve done it—it’s fun). And here begins one of the greatest rivers in the world.

The Mississippi leaves the lake at 1475 feet above sea level and falls gently—very gently—to the sea below New Orleans. A drop of water leaving Lake Itasca takes about three months to hit the ocean. And it is a long journey, somewhere above 2,350 miles—different sources report different lengths, with Itasca State Park claiming the longest, at 2,552 miles. The Missouri River, which is a tributary of the Mississippi, is actually about 100 miles longer. When the entire length of the Missouri-Mississippi is combined, the river’s 3,710-mile length makes it the fourth longest in the world, behind the Nile, Amazon and Yangtze Rivers.

The watershed of the Mississippi is just as impressive, covering all or part of 32 states and a sliver of 2 Canadian provinces. The total area, 1.2 million square miles, includes about 40% of the continental United States. The river’s two main tributaries are the Missouri, flowing from the West, and the Ohio, flowing from the East. The Ohio River stretches the definition of a tributary, as it actually carries more water than the Mississippi where the two meet in Cairo, Illinois.

The Mississippi has always held a central role in American culture (e.g., the writings of Mark Twain) and commerce. The US Army Corps of Engineers has built and maintains 29 locks and dams in the upper Mississippi that allows boat and barge traffic from Minneapolis to the ocean. The Midwestern farmlands of the Mississippi watershed are the nation’s “bread-basket,” and most of the nation’s agricultural exports start there, travel on barges down the river and leave through the Port of New Orleans. Adds to that exports of petroleum products and other bulk commodities, and the several ports in the New Orleans area together comprise the largest port district in the world.

The river is subject to frequent floods, as snow-melt from the West and spring rainfall from the East and Midwest swell its discharge. The largest occurred in 1927, when the river was 80 miles wide in some places. That flood led to massive interventions by the US Army Corps of Engineers, building levees and other control structures. Massive flooding followed in 1937, 1973, and as recently as 2019.

The river and its watershed are equally important for conservation. The Mississippi Flyway is the route for 40% of the nation’s migratory waterfowl moving semi-annually between breeding grounds in Canada and wintering grounds in the southern U.S. and Latin America. One quarter of all freshwater fish species in North America live in the watershed and 560% of all bird species.

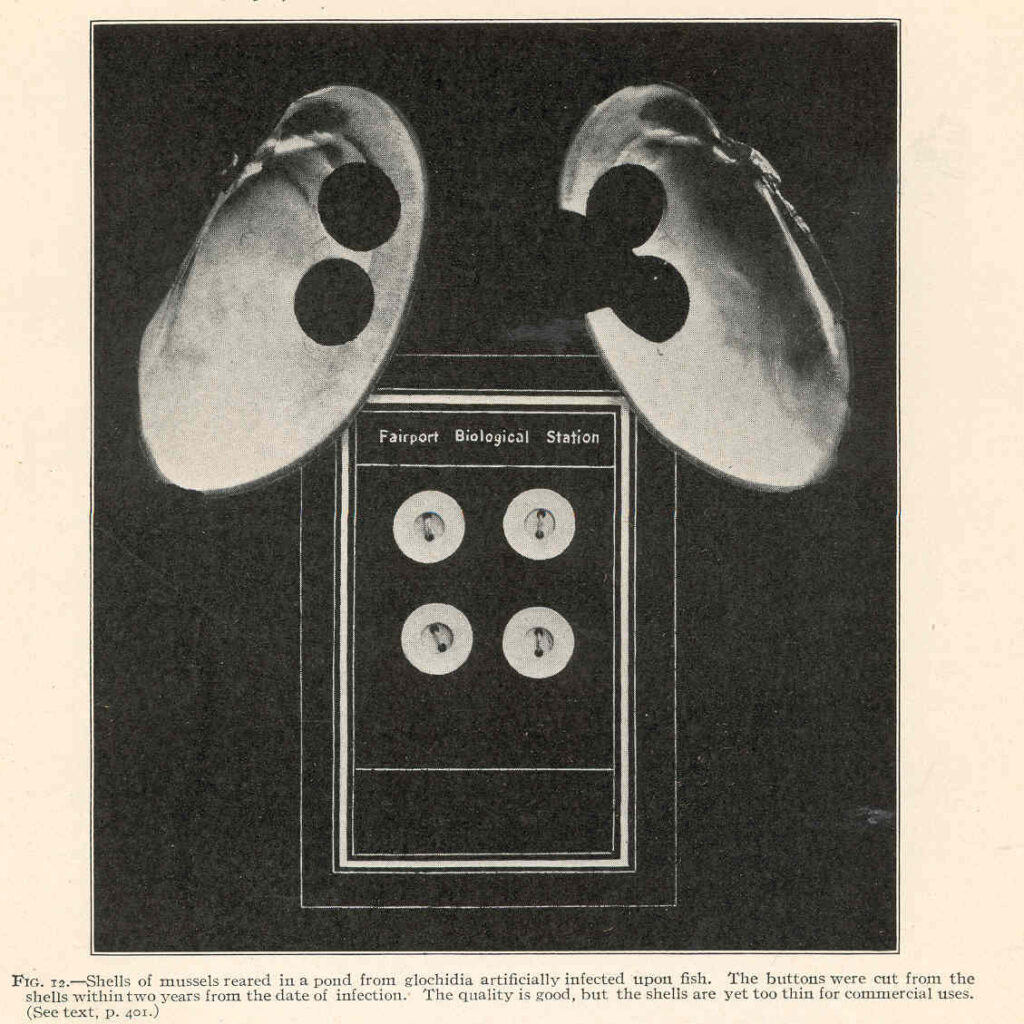

Of particular importance is the diversity of freshwater mussels. Most of the 39 species live in the clear upper waters of the Mississippi. For about 40 years bracketing the start of the 20th Century, the shells of these mussels were heavily exploited to make buttons, an industry ended when plastic buttons took over. Today, commercial mussel harvest is prohibited to protect the dwindling populations of the animals, which have also been impacted by dams, sedimentation and pollution. Several species are endangered, listed either by the federal or state governments.

Altogether, the Mississippi River shows us how important and how fickle are the rivers of nature. As Mark Twain said:

“One who knows the Mississippi will promptly aver—not aloud, but to himself—that ten thousand River Commissions, with the mines of the world at their back, cannot tame that lawless stream, cannot curb it or confine it, cannot say to it, Go here, or Go there, and make it obey; cannot save a shore which it has sentenced; cannot bar its path with an obstruction which it will not tear down, dance over, and laugh at.”

References:

Garth, Gary. 2016. American beginnings: The source of the Mississippi River. USA Today, Nov. 4, 2016. Available at: https://www.usatoday.com/story/travel/destinations/2016/11/04/mississippi-river-source-headwaters/93241254/. Accessed March 23, 2020.

National Park Service. Mississippi River Facts. Available at: https://www.nps.gov/miss/riverfacts.htm. Accessed March 23, 2020.

National Weather Service. Mississippi River Flood History 1543-Present. Available at: https://www.weather.gov/lix/ms_flood_history. Accessed March 23, 2020.

State Historical Society of Missouri. Henry Row Schoolcraft. Available at: https://historicmissourians.shsmo.org/historicmissourians/name/s/schoolcraft/. Accessed March 23, 2020.

Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. Freshwater mussels of the Mississippi River. Available at: https://dnr.wi.gov/topic/watersheds/basins/mississippi/mussels.html. Accessed March 23, 2020.