Taxonomy as we know it began on May 1, 1753. Before then, the naming and description of species was a free-for-all. Species were described by long, cumbersome Latin names that were given randomly by different observers. A single species might have several names that the originator changed at will. The common wild briar rose, for example, was called Rosa sylvestris inodora seu canina by one botanist and Rosa sylvestris alba cum rubore, folio glabro by another. From now on, that would be different.

Linnaeus is a name familiar to anyone who has taken a biology course. Carl von Linne, or as we know him, Carolus Linnaeus, was born in 1707 in Sweden, studied medicine and became a prominent Swedish doctor, eventually serving as the physician to the Swedish royal family. His family name was taken from the linden tree, a favorite of his father, a minister.

Like his father, Linnaeus loved plants. At the time, studying plants was part of studying medicine, because doctors needed to know which plants to prescribe as drugs for their patients’ ailments. But Linnaeus’ interest went much farther. He explored the agricultural and economic uses of plants, including creating gardens and indoor growing environments in which he hoped to produce varieties of tropical plants that could grow in Sweden. He wasn’t particularly successful in that work.

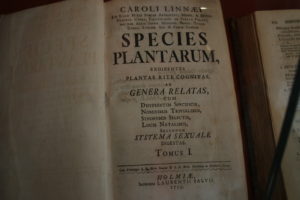

He was successful, however, in figuring out a way to organize plant identification that was simple and standard. He created the binomial system we use today, designating a plant’s identification by a genus name and a species name, both in Latin so that common names wouldn’t confuse botanists and the public. He worked on this gradually over years, eventually publishing Species Plantarum on May 1, 1753. He named the wild briar rose Rosa canina.

Species Plantarum inventoried and classified every known plant at the time, 6,000 species in all. The book immediately became the standard way to classify organisms, marking its publication as the historical beginning of modern taxonomy. His innovation allowed much better communication among scientists and also allowed the public to participate in botanical exploration and discovery.

Linnaeus followed up his botanical treatise with a complete binomial taxonomy of known plants and animals in 1758, the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae. The biological basis of his classification was challenged because he used only sexual characteristics in his ordering of plants—some considered it too restrictive, and others thought it was obscene. But his system of classification—genus and species—has become standard.

Some also consider Linnaeus a pioneer in ecology. He understood that the relationship between a plant and its environment was crucial to its success. That is why he was so convinced that he could breed plants with traits that were more adapted to the cold environment of Sweden.

So, next time you complain about having to learn the two-name scientific identification of a plant or animal, stop and thank Linnaeus that you can describe a species in two words–instead of a paragraph of nonsense!

References:

Encyclopedia Britannica. Species Plantarum. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Species-Plantarum. Accessed April 30, 2018.

University of Aberdeen. Carolus Linnaeus, Species Plantarum. Available at: https://www.abdn.ac.uk/special-collections/carolus-linnus-species-plantarum-458.php. Accessed April 30, 2018.

University of California Museum of Paleontology. Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778). Available at: http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/history/linnaeus.html. Accessed April 30, 2018