London in the 1850s was a stinking mess. Air pollution was terrible, but water pollution had reached the breaking point. An engineer named Joseph Bazalgette changed much of that by building the Thames Embankments. The final section, called the Chelsea Embankment, was opened on May 9, 1874, by Prince Alfred, completing one of the great engineering projects of the Victorian Era.

London was a huge city by the 1850s, with millions of residents. But it had nothing close to an organized sanitation system. Where sewers did exist, they emptied into scores of small rivers that ran open and putrid to the Thames—which also ran putrid. Things got really bad in the summer of 1858, known as the year of the Great Stink. Abnormally low flows in the Thames coupled with abnormally high temperatures made the Thames a swamp of stinking human wastes. So bad was the stench that Parliament had to suspend operations and Queen Victoria, out for a cruise down the river, was turned back after a few minutes.

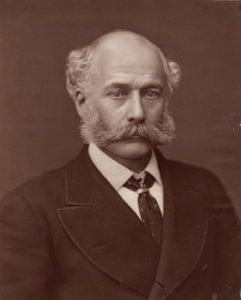

Something had to be done, and the engineer Joseph Bazalgette had the answer. He proposed to build a series of giant sewers that ran along the two banks of the Thames, collecting the outfall of smaller sewers and carrying them miles downstream, beyond the sight—and smell—of Londoners. The project was approved, and Bazalgette set to work.

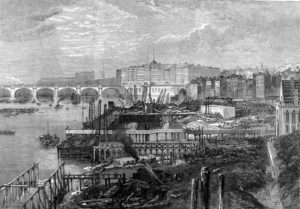

His project wasn’t just a set of sewer pipes. It involved the entire transformation of the Thames River in central London. Up to then, the Thames had broad, sloping banks that formed wide mud flats at low tide. Bazalgette’s project narrowed the river within high straight stone walls. Behind the walls and below the ground surface, he built sewers, of course, but also tunnels for trains (the famous London Underground) and channels for other needs, like electric cables and telephone lines. On top, he built a road, with walkways along the river and on the land side of the road. Gardens planted with trees at 20-foot intervals filled the intervening spaces.

The project was immense, and expensive. Begun in 1859, it continued through 1874. The total project includes the Albert, Thames and Chelsea Embankments, covering both sides of the river for a distance of more than five miles. Bazalgette not only solved the current issues, but anticipated the future. He estimated the population of London, generously estimated how much each person would produce in sewage, and then doubled that amount to accommodate future growth. The capacity of his sewers served the city for 80 years, until new capacity had to be designed.

The results produced marked improvements in public health. Cholera, which is spread through contaminated water and had occurred in regular outbreaks in London, basically disappeared in the area covered by the new structures. Public pride also soared. A river that Londoners were “converting…into a sewer” became “a magnificent promenade.”

Bazalgette’s achievement is one example of the growing concern that Americans and Europeans had for their diminished environments during the last half of the 19th Century. As the nastiest leavings of the industrial movement made shambles of urban areas around the civilized world, a growing movement began—and we all benefit from it today.

References:

Broich, John. 2013. London—Water and the Making of the Modern City. University of Pittsburgh Press, 214 pages (p. 47-48).

Grace’s guide to British Industrial History. Joseph Bazalgette. Available at: https://www.gracesguide.co.uk/Joseph_Bazalgette. Accessed May 4, 2018.