The Rio Grande is one of North America’s great rivers, travelling 1885 miles from headwaters in Colorado, through New Mexico and forming the border between the U.S. and Mexico for more than 1200 miles in Texas. Yet, because of extensive water withdrawals, in many years, the Rio Grande dries up before it reaches the sea.

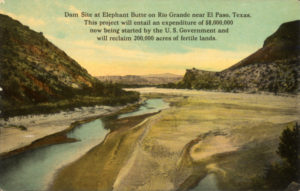

To bring order to water withdrawals between Mexico and the U.S., the two countries have entered into water-sharing agreements. The first was signed on May 21, 1906. It requires the U.S. to provide Mexico with 60,000 acre-feet of water annually from the upper region of the watershed. That water generally comes from Elephant Butte Reservoir, in central New Mexico, which is a major water-storage impoundment providing water for irrigation and municipal use in New Mexico and the El Paso-Juarez region. The river often stops flowing south of Elephant Butte because the water is all allocated and withdrawn, leaving none for the channel itself.

The second agreement was signed in 1944. It allocates water from the lower region of the river, downstream of El Paso. This treaty requires Mexico to provide 350,000 acre-feet of water to the U.S. from its tributaries annually; the U.S. does not have to provide any water from its tributaries to Mexico. The river often also dries up in this region because of water withdrawals, and often is empty when it reaches the ocean. Because of the use of water, the Rio Grande is often considered two rivers, upstream and downstream, rather than one.

The Rio Grande is a good example of a reality that is common around the world. Rivers often form the borders between nations, and, therefore, their watersheds and water flows are shared among nations. According to the UN, nearly half of the earth’s surface is in watersheds shared by two or more countries, through a total of 263 rivers and lakes that serve as national borders. Transboundary waters, as they are called, involved 145 nations.

Often, rivers connect many more than two nations. Nineteen water basins are shared by more than five countries, including the Congo, Nile, Rhine and Zambezi. The Danube, which runs through central Europe, flows through 18 countries!

As Mark Twain famously said, “Whiskey is for drinking, water is for fighting.” To avoid fighting, more than 3600 treaties, conventions and other agreements have been negotiated to allocate the water in shared watersheds. Today, most countries deal peacefully with their neighbors about water, even when they may engage in violent and long-running contests over other issues, such as religion, immigration or borders. The UN cites that the last half-century has seen only 37 aggressive disputes over water, while 150 treaties have been signed. Consequently, an entire discipline has developed in international affairs to address water-sharing concerns—water diplomacy.

Water, as we know, is the most valuable resource. And nations, even warring nations, understand that their short-term and long-term existence depends on the orderly and rational allocation of the water that nature makes them share.

References:

Carter, Nicole T. et al. 2017. U.S.-Mexican Water Sharing : Background and Recent Deveopoments. Congressional Research Service. Available at: https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R43312.pdf. Accessed May 21, 2018.

International Boundary & Water Commission. Treaties Between the U.S. and Mexico, Convention of May 21, 1906. Available at: https://www.ibwc.gov/Treaties_Minutes/treaties.html. Accessed May 21, 2018.

Rister, M. Edward et al. 2001. Challenge and Opportunities for Water of the Rio Grande. Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics 43(3):367-378. Available at: https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/113529/2/jaae433ip6.pdf. Accessed May 21, 2018.

United Nations. International Decade for Act ‘Water For Life’ 2005-2015. Available at: http://www.un.org/waterforlifedecade/transboundary_waters.shtml. Accessed May 21, 2018.