November 30 sports a number of events that relate to conservation. The Welland Canal first opened in 1829, allowing all sorts of environmental chaos to travel past the natural barrier of Niagara Falls. Australia experienced its hottest November ever in 2014, a tribute to climate change. The Paris Climate talks began on this date in 2015 (see the results on December 12, the day it ended).

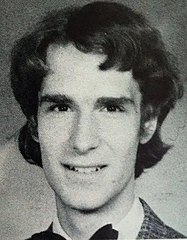

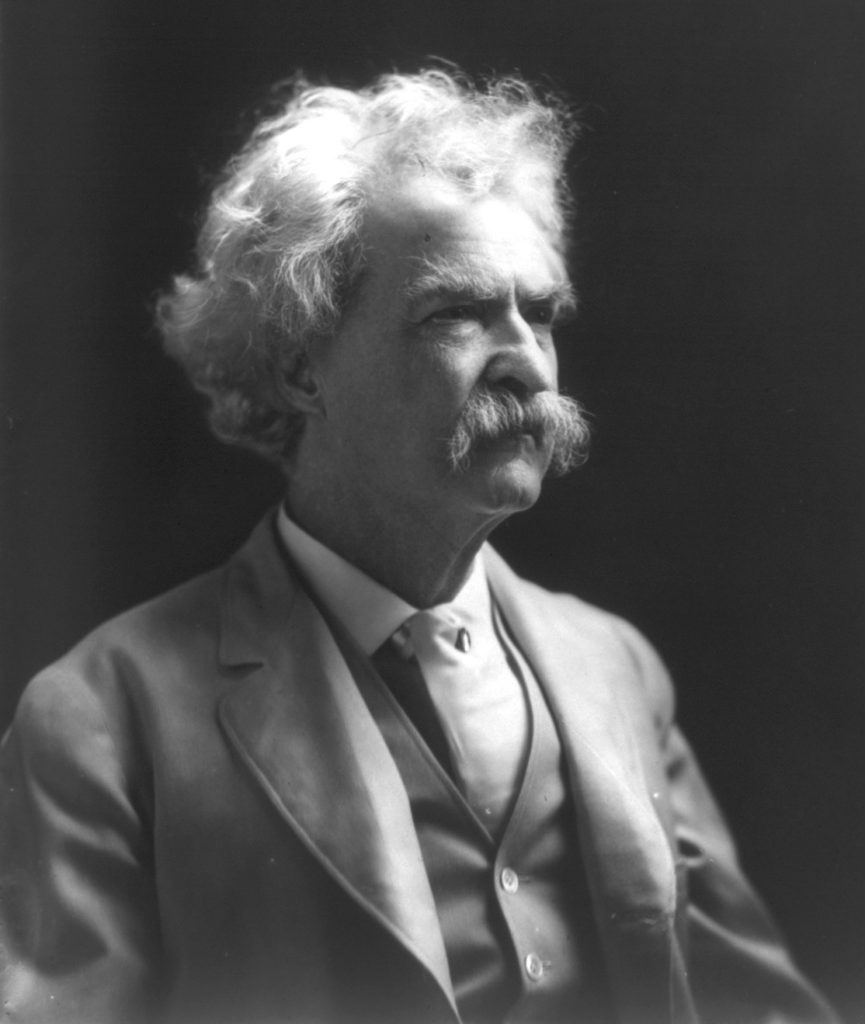

But I’ve chosen to highlight Mark Twain’s birthday on November 30, 1835 (died 1910). Mark Twain needs no introduction. He was born in Missouri, lived most of his youth in the Mississippi riverbank town of Hannibal, and is most notably associated with the river and its immediate surroundings. The world loves Twain for his humorous homespun stories, from The Adventures ofTom Sawyer to Huckleberry Finn to The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County. Beyond humor, however, his writing was often satirical and sometimes cynical, about life and human nature.

Twain was an adventurer as well as a writer. He spent many years tramping, as he would say, around the U.S. and the world. He travelled to Hawaii and across the American West, working as a travelling correspondent for various newspapers and magazines. He wrote a collelction of stories of his western adventures in Roughing It. He spent years as a riverboat pilot on the Mississippi River, and recounted his experiences in his book, Life on the Mississippi. He also travelled around Europe and the Middle East. His time in England was the basis for his magical tale of A Yankee in King Arthur’s Court.

Let’s enjoy a few of the ideas that Mark Twain left us regarding nature and our relationship to it.

“This is the fairest picture on our planet, the most enchanting to look upon, the most satisfying to the eye and spirit. To see the sun sink down, drowned in his pink and purple and golden floods, …is a sight to stir the coldest nature, and make a sympathetic one drunk with ecstasy.”

“Architects cannot teach nature anything.”

“The laws of Nature take precedence of all human laws. The purpose of all human laws is one — to defeat the laws of Nature. This is the case among all the nations, both civilized and savage. It is a grotesquerie, but when the human race is not grotesque it is because it is asleep and losing its opportunity.”

“Nature knows no indecencies; man invents them.”

“Each season brings a world of enjoyment and interest in the watching of its unfolding, its gradual harmonious development, its culminating graces-and just as one begins to tire of it, it passes away and a radical change comes, with new witcheries and new glories in its train.”

“To one in sympathy with nature, each season, in its turn, seems the loveliest.”

“Change is the handmaiden Nature requires to do her miracles with.”

References:

AZ Quotes. Mark Twain Quotes About Nature. Available at: https://www.azquotes.com/author/14883-Mark_Twain/tag/nature. Accessed December 3, 2019.

Mark Twain Quotes. Nature. Available at: http://www.twainquotes.com/Nature.html. Accessed December 3, 2019.

Quirk, Thomas V. 2019. Mark Twain, American Writer. Encyclopedia Britannica, Nov 11, 2019. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Mark-Twain. Accessed December 3, 2019.