The public is fascinated by sharks today—Shark Week, Sharknado, and the rest. The person who did the most to bring sharks to such popularity is the woman known to the world as “The Shark Lady,” Dr. Eugenie Clark.

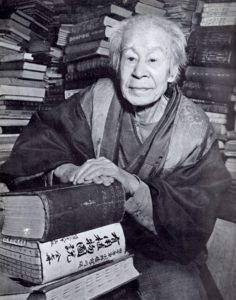

Eugenie Clark was born on May 4, 1922, in New York City, daughter of a Japanese mother and American father (died in 2015). Her father died when she was an infant, and her mother married a Japanese man; consequently, Clark was brought up in the sea-loving Japanese culture, which she later said nurtured her interest in oceans and fish. She made frequent trips to the New York Aquarium as a child, imagining what it would be like to be inside the aquarium swimming with the sharks.

She followed her passion for the living sea, earning an undergraduate degree at Hunter College in zoology and masters and doctoral degrees at New York University in ichthyology. It was an uncomfortable world for women at the time, with restrictions on travel on research vessels and to distant field sites. But it didn’t stop Clark, who said later, “I never let being a woman—even as a young girl—stop me from trying to do something I really wanted to do, especially if it concerned fishes or the underwater world.”

And she went places and did things that others, including men, didn’t. She learned to dive in the 1940s, first using helmets and air hoses, later using scuba equipment. She studied fishes in Micronesia, learning to free dive from the local fishermen. She took more than 70 dives in deep-sea submersibles.

She went to study the fishes of the Red Sea in 1950, an area that had been ignored by scientists. She called it a “virgin sea.” She discovered several fish species while there, and the Red Sea became one of her passions. Her continuing efforts to protect unique reef areas in the Red Sea led to their preservation as Egypt’s first national park in 1983. She published a memoir of her 1950s work in the Red Sea, entitled Lady With a Spear, that became an international best seller.

But through it all, sharks remained Clark’s primary interest. She thought sharks were misunderstood, saying “After some study, I began to realize that these ‘gangsters of the deep’ had gotten a bad rap.” She proved sharks were smart by teaching them to push on different shaped and colored buttons to receive food. She dispelled the idea that sharks had to swim continuously to move water across their gills, discovering the “sleeping sharks” in marine caves along the Yucatan Peninsula. Over time, she became known as The Shark Lady.

In 1954, she attracted the attention of the Vanderbilt family, who invited her to give a seminar at their Florida estate. The whole town turned out, as she remembered, “They were fascinated—the fishermen, families, children—they all just loved hearing about fishes in the Red Sea and the exotic places I had been to.” The Vanderbilt’s had a hidden agenda. After the talk, they suggested she stay and start a marine laboratory with their financing. “How often do you get an offer like that?” Clark recalled. The next year, the new laboratory opened, and it has been going ever since. Now known as the Mote Marine Laboratory, in Sarasota, her one-person start-up has become a world-famous scientific and public education institution.

Like so many leading conservationists, her ability to combine the best of science with the best of public education is a hallmark of Clark’s career. Along with scores of scientific papers, she wrote many articles for National Geographic, especially about sharks. From 1968-1992, she was a professor at the University of Maryland, with an adoring following of undergraduate students. A colleague wrote that “her ability to connect to the general public and talk about the importance of exploration and protection of oceans and conservation of species.”

Eugenie Clark kept at it to the end. On her 92nd birthday, she went for a dive in her beloved Red Sea. Despite her age, said her diving companion, “The minute she was underwater, she was as graceful as a ballerina.”

Perhaps it would be more fitting to say she was as graceful as a shark.

References:

Rutger, Hayley. 2015. Remembering Mote’s “Shark Lady”: The Life and Legacy of Dr. Eugenie Clark. Mote Marine Lab, March 5, 2015. Available at: https://mote.org/news/article/remembering-the-shark-lady-the-life-and-legacy-of-dr.-eugenie-clark. Accessed May 1, 2018.

National Ocean Service. Dr. Eugenie Clark (1922-2015). Available at: https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/news/may15/eugenie-clark.html. Accessed May 1, 2018.

Stone, Andrea. 2015. ‘Shark Lad’ Eugenie Clark, Famed Marine Biologist, Has Died. National Geographic, February 25, 2015. Available at: https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2015/02/150225-eugenie-clark-shark-lady-marine-biologist-obituary-science/. Accessed May 1, 2018.

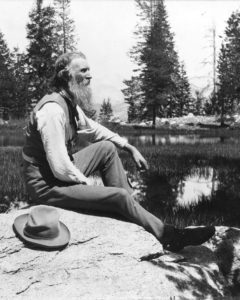

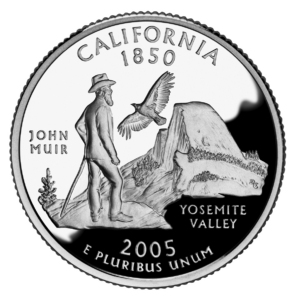

Muir was a complex man. He was deeply spiritual, but hated organized religion. He loved people individually and was the life of the party wherever he went, but he distrusted organizations of all kinds. He never considered himself a citizen of anything but the earth. He loved hiking in the wilderness alone, but craved the company of those he loved.

Muir was a complex man. He was deeply spiritual, but hated organized religion. He loved people individually and was the life of the party wherever he went, but he distrusted organizations of all kinds. He never considered himself a citizen of anything but the earth. He loved hiking in the wilderness alone, but craved the company of those he loved.