In 1989, the United Nations created a day to recognize the damage done to humanity by natural disasters and to exhort nations to reduce the risk associated with those disasters. The day also recognizes that natural disasters, “many of which are exacerbated by climate change, have a negative impact on investment in sustainable development and the desired outcomes.” In 2009, the UN chose October 13 as its permanent annual recognition of the need for disaster risk reduction.

A twenty-year review of natural disasters by the UN demonstrated the rising costs, both economic and human, of disasters. Compared to the early two decades, the period from 1998 to 2017 experienced a 151% increase in the economic losses from disasters, rising from $1.3 billion to $2.9 billion, Climate-related disasters accounted for 77% of the total loss (earthquakes and the resultant tsunamis were most of the rest). The vast majority of climate-related events were floods (43.4%) and storms (28.2%).

While the human costs of these disasters get the most attention, of course, the costs to biodiversity are similarly terrible. A 2019 report by the National Wildlife Federation described the consequences of several recent events to wildlife. Record July temperatures in Alaska caused die-offs of pink, sockeye and chum salmon. Hurricane Irma in 2017 devastated southern Florida, including killing up to 22% of the remaining population of the endangered key deer. Massive fires in the western U.S., including the 2016 Soberanes Fire, choked streams with sediment and other debris, affecting fish and amphibian species with nowhere else to go. Floods associated with Hurricane Harvey in 2017 killed almost all of the remaining wild population of the endangered Attwater’s Prairie Chicken (only 12 birds remained alive after the floods).

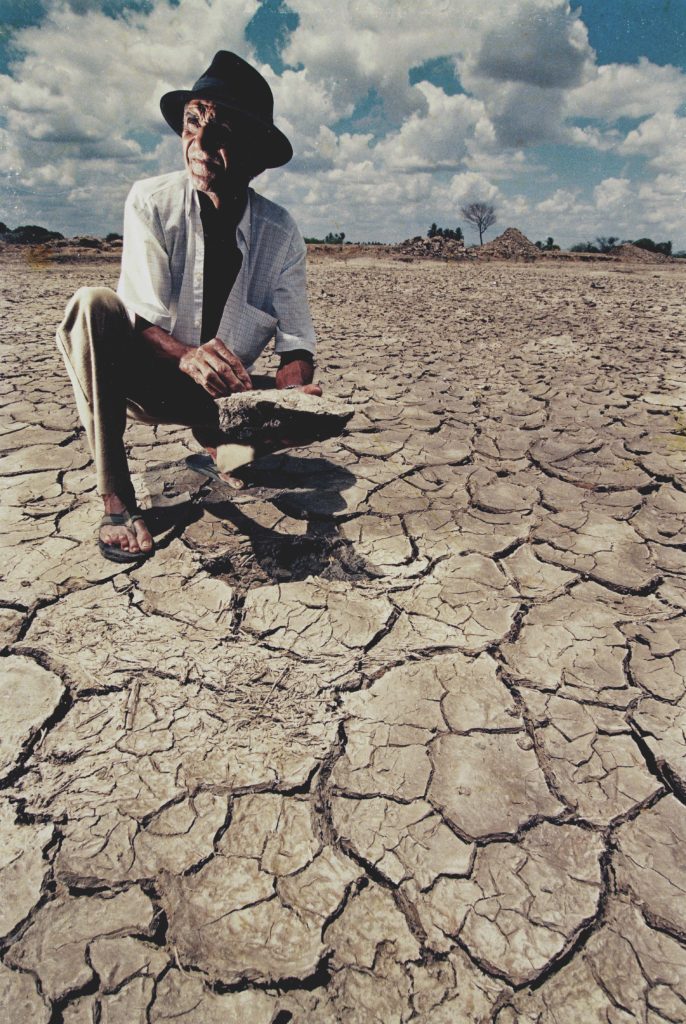

Natural disasters always cause losses, of course, but climate change is making these disasters worse. More water in the atmosphere and warmer temperatures in both the air and water make storms larger, more frequent and more violent. Weather events are getting more episodic, with higher rainfalls during storms causing bigger floods and longer droughts between storms causing habitat degradation and extreme wildfires.

Which brings us back to the United Nations resolve to manage the risks of natural disasters better. Communities and nations need to make their infrastructure and neighborhoods more resilient in the face of these increasingly violent episodes—that’s what is called climate adaptation. But, more fundamental to our overall sustainability, is the other needed response: mitigating climate change. Mitigation means reducing the amount of greenhouse gases building up in the atmosphere by reducing fossil fuel burning. Let’s just do it!

References:

NASA Earth Observatory. 2005. The Impact of Climate Change on Natural Disasters. Available at: https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/features/RisingCost/rising_cost5.php. Accessed February 6, 2020.

National Wildlife Federation. 2019. Climate Change, Natural Disasters, and Wildlife. Available at: https://www.nwf.org/-/media/Documents/PDFs/Environmental-Threats/Climate-Change-Natural-Disasters-fact-sheet.ashx. Accessed February 6, 2020.

UN Office of Disaster Risk Reduction. 2018. UN 20-year review: earthquakes and tsunamis kill more people while climate change is driving up economic losses. Available at: https://www.undrr.org/news/un-20-year-review-earthquakes-and-tsunamis-kill-more-people-while-climate-change-driving. Accessed February 6, 2020.