We know it by heart: “I am the Lorax. I speak for the trees. I speak for the trees, for the trees have no tongues.” The trees got their voice on this day, August 12, in 1971, when Dr. Seuss published The Lorax.

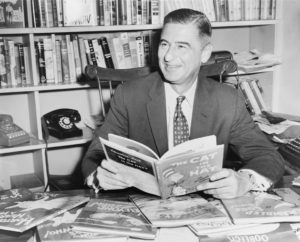

Dr. Seuss is one of the most beloved authors in 20th Century American literature. Kid’s literature, true, but I’d guess that every adult still thrills to read his anapestic tetrameter, see his phantasmagoric drawings and escape to his whimsical worlds.

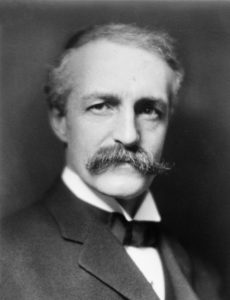

Dr. Seuss was born as Theordor Geisel in 1904 in Springfield, Massachusetts (died 1991). He was an industry cartoonist, and Standard Oil was his biggest client. But he wanted to accomplish more significant work, writing serious books. The only problem was that his Standard Oil contract forbade almost every kind of moonlighting. There was one loophole—he could write for children. And so he did, writing and drawing more than 60 books, many of which can be found in every child’s room in America. He wasn’t immediately successful—his first book (And To Think I Saw It On Mulberry Street) was turned down by 26 publishers before hitting bookshelves in 1937.

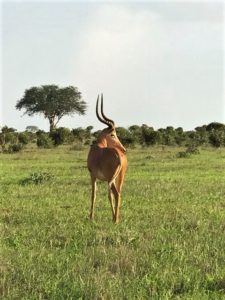

Fast-forward to the start of the 1970s. Seuss, now a publishing whirlwind, was living in La Jolla, California, and was increasingly disturbed by the commercialization of the town and its environment. He decided to write a book about taking care of the world rather than just exploiting it. But he was blocked, unable to grasp how to present his ideas. A friend took him to Kenya for inspiration, and while watching a herd of elephants, inspiration struck. Back at camp, he sat down and wrote the text for The Lorax on the back of a laundry slip—in 90 minutes!

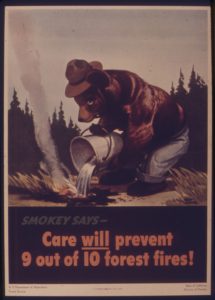

When the book hit stores in 1971, it wasn’t very popular. Readers and critics were disappointed that this story was serious, a downer compared to the zany tales they had come to expect. Some politicians and forestry leaders objected to what they saw as an indictment of the logging industry. After all, the Once-ler did cut down every last Truffula Tree to turn them into Thneeds.

But Dr. Seuss didn’t intend it that way. The book was about conservation, not preservation. Seuss didn’t object to logging, just to logging that was excessive and thoughtless. He said, “The Lorax doesn’t say lumbering is immoral. I live in a house made of wood and write books printed on paper. It’s a book about going easy on what we’ve got. It’s anti-pollution and anti-greed.” He wanted to support the idea of sustainability—to live today so that others can live as they wish later.

As the environmental movement gained traction, so did The Lorax. When Lady Bird Johnson, the U.S. First Lady, began her environmental work, she positioned The Lorax at the center of her campaign. Anti-logging sentiment in the West also drove sales of the book, perhaps spurred by a rebuttal book by the logging industry called Truax. Since then, The Lorax has sold more than one million copies and been adapted into a feature film and TV special. It sits at 33 on the list of the 100 best picture books of all time as judged by school librarians (in 12th place is another Seuss book, Green Eggs and Ham).

The Lorax is far from Dr. Seuss’ most popular book, however. Green Eggs and Ham takes that honor, also, with about 8 million copies sold. In all, Dr. Seuss’ books have sold about 70 million copies, making him the most popular children’s author of all time.

So three cheers for Dr. Seuss, whether he’s just making us smile or also making us think. And let’s get out there and plant some real-life equivalent of Truffula Trees!

References:

Ayers, Kyle. 2012. The Environmental Message Behind ‘The Lorax.’ CBS New York, April 9, 2012. Available at: http://newyork.cbslocal.com/2012/04/09/the-environmental-message-behind-the-lorax/. Accessed June 14, 2018.

Barber, Bonnie. 2012. Professor Donal Pease Shares the ‘Story Behind The Story’ of The Lorax. Dartmouth News, February 29, 2012. Available at: https://news.dartmouth.edu/news/2012/02/professor-donald-pease-shares-story-behind-story-lorax. Accessed June 14, 2018.

Bird, Elizabeth. 2012. Top 100 Picture Books Poll Results. School Library Journal. Available at: http://blogs.slj.com/afuse8production/2012/07/06/top-100-picture-books-poll-results/#_. Accessed June 14, 2018.

Priceonomics. 2001. The Statistical Dominance of Dr. Seuss. Available at: https://priceonomics.com/the-statistical-dominance-of-dr-seuss/. Accessed June 14, 2018.