They are called “Lazarus species” because, like the biblical Lazarus, they appear to return from the dead. On January 28, 1951, the Bermuda Petrel joined the very short list of species that have been re-discovered.

The Bermuda Petrel (Pterodroma cahow) is a rare bird today, but once was amazingly abundant in its Bermuda home. It is known locally as the “cahow,” after its distinctive and terrifying cry. A Spanish sea captain in 1603 wrote about the sound as many birds flocked around his ship: “At dusk, such a shrieking and din fill the air that fear seized us….These are the devils reported to be about Bermuda. The sign of the cross at them! We are Christians!”

The cahow nested on Bermuda and outlying islands, digging deep cavities in the ground where they laid and cared for eggs and chicks. When chicks fledged, they flew out across the ocean, to grow and feed on the wing for up to five years before returning to the islands to breed. They are about the size of pigeons, but with an out-sized wingspan supporting their oceanic flights. Black or gray above, their undersides are bright white.

The species was a god-send to settlers on Bermuda and the sailors who landed there. Rather than fearing humans, the birds were attracted to the lights of their fires and to loud sounds made to draw them in. They would land on an outstretched arm, becoming easy prey for a club. Tasting delicious, both the birds themselves and their eggs were heavily exploited. Just a few years after that captain’s 1603 description of their fearful cries, the birds were almost gone. So worried were the locals that a law was passed in 1616—considered the first conservation law in the New World—that prohibited their capture.

But enforcement was lax, and harvest continued. Introduced mammals—pigs and rats especially—destroyed their nests and ate their eggs. And then they were gone. For three centuries, no person saw or heard a cahow, and there were no specimens in museums or private collections. The species was extinct and unknown to science.

But in the early 1900s, reports of possible sightings of cahows began to dribble in. In 1906, a specimen was killed on Bermuda that might have been a cahow, renewing interest in finding living birds. In 1935, the famous biologist William Beebe was given a dead bird by a boy in Bermuda; he identified it as an immature cahow. During World War II, an American soldier stationed on Bermuda found some dead birds on a small uninhabited island that he thought might be cahows.

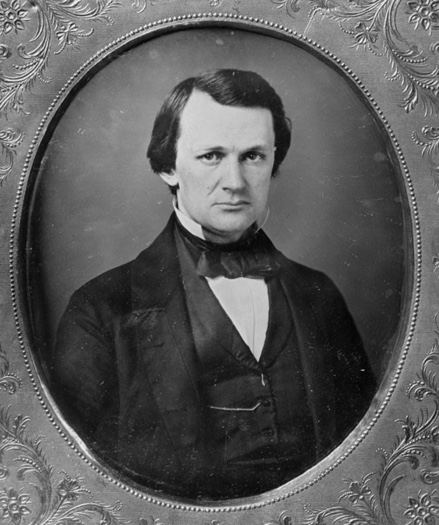

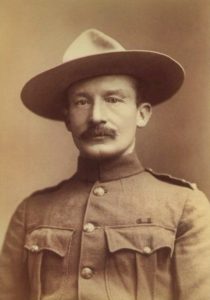

The breakthrough came in early 1951. The occasional reports of cahows encouraged the NY Museum of Natural History to go looking. Robert Murphy, an ornithologist at the museum and Louis Mowbray, the son of the man who found the 1906 bird, set out to explore several small rocky islands, places where nesting was possible and probably unobserved. Accompanying them was a 16-year-old local boy, David Wingate. Wingate recounted the event:

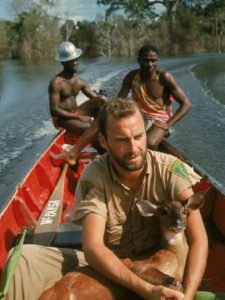

“For days, gales prevented any visit to the offshore islands. The weather finally moderated on Jan. 28, 1951, and with a heavy sea still running, one last‐ditch attempt was made…. After several difficult landings, we finally found an islet which offered some faint but hopeful evidence of occupancy: a patch of greenish‐white excreta and a half‐obliterated footprint at the entrance of an extremely deep and curved tunnel in the cliff…. After much digging a bird was finally revealed sitting on an egg.”

They found a bird in a nesting tunnel, lassoed it and yanked it to the light. It was a living cahow! The long extinct Bermuda petrel had risen from the dead! In all, they found 18 nesting pairs of cahows on the island.

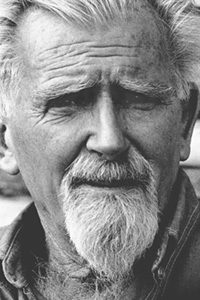

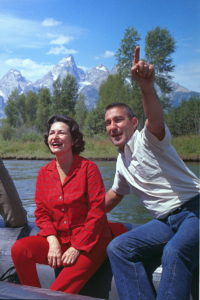

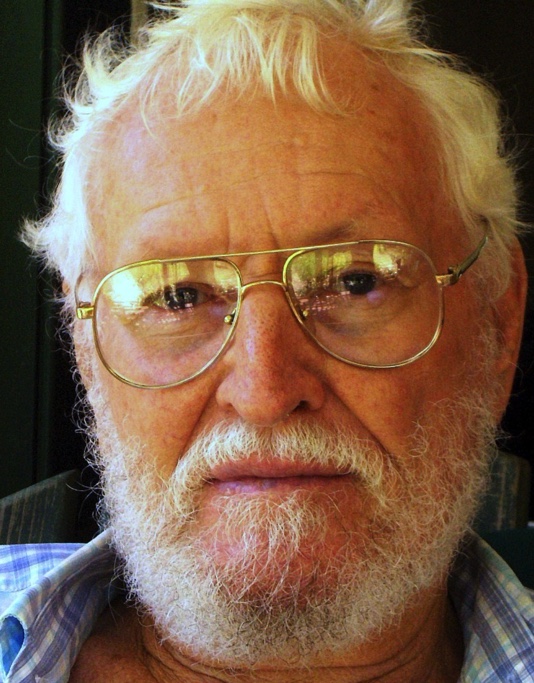

That expedition changed life for David Wingate. He dedicated his future career to saving this rare bird and the natural heritage of Bermuda. He attended Cornell to study ornithology, but soon returned to become Bermuda’s first professional wildlife officer. He personally directed the restoration of native vegetation on Nonsuch Island, which has regrown into a tropical forest. The island, one of the world’s earliest examples of ecological restoration, is now part of Castle Harbor Islands Nature Reserve.

And the cahow continues to do well. From the original 18 nesting pairs in 1951, the population had grown to 98 nesting pairs and 250 individuals by 2011, and the positive trend continues. IUCN lists the species as endangered—a far cry from 300 years considered as extinct.

References:

IUCN Red List. Pterodroma cahow. Available at: http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/full/22698088/0. Accessed January 30, 2018.

Mowbray, Louis. 1951. The Cahow Rediscovered. The Bermudian, April, 1951. Available at: http://www.thebermudian.com/heritage/life-in-old-bda/617-april-1951. Accessed January 30, 2018.

Zimmerman, David R. 1973. The cahow: saved from hog, rat and man. The New York Times, December 2, 1973. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/1973/12/02/archives/no-longer-extinct-the-cahow-saved-from-hog-rat-and-man-cahow-david.html. Accessed January 30, 2018.