In the United States, wildlife belongs to the state in which it lives. And the individual states have the authority to regulate the management of that wildlife. Before 1900, unscrupulous hunters took advantage of a legal loophole by poaching animals in one state and then moving them to another state where the harvest and sale of the animals was legal. States were helpless to control the change in jurisdiction because they could not regulate interstate commerce.

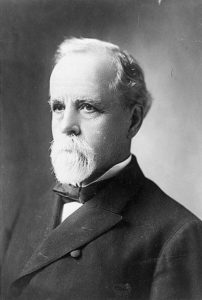

Until 1900, that is, when the Lacey Act became federal law. John Lacey, an Iowa congressional representative, was concerned about the effect of dwindling wildlife and the importation of exotic species that became agricultural nuisances. He introduced a bill to control both. The bill, known as the Lacey Act of 1900, passed congress in late April and President William McKinley signed it into law on May 25, 1900. The Lacey Act became the first federal wildlife regulation.

And it has remained one of the most effective conservation laws in history. The law made illegal the interstate commerce of wild animals or their parts if killed in violation of a state law. No longer could poachers kill protected animals in one state and sneak them into another state where their possession and sale were legal. Coupled with state laws that made market hunting illegal within an individual state (which most states enacted soon after this), the Lacey Act effectively stopped market hunting in the United States.

The Lacey Act has been amended many times over its century of implementation. It now covers not only wild birds and mammals, but also fish and other aquatic organisms, plants and any wildlife taken in violation of international laws. The most pertinent section of the law reads in part as follows:

“It is unlawful for any person – (1) to import, export, transport, sell, receive, acquire, or purchase any fish or wildlife or plant taken, possessed, transported, or sold in violation of any law, treaty, or regulation of the United States or in violation of any Indian tribal law; (2) to import, export, transport, sell, receive, acquire, or purchase in interstate or foreign commerce – (A) any fish or wildlife taken, possessed, transported, or sold in violation of any law or regulation of any State or in violation of any foreign law; (B) any plant taken, possessed, transported, or sold in violation of any law or regulation of any State; or (C) any prohibited wildlife species (subject to subsection (e) of this section);….”

Other parts of the law regulate the marking of wildlife so that the origin can be confirmed; define that guides are subject to the law; regulate importation of various species considered ecologically dangerous; and outlaw “animal terrorism,” meaning attempts to interfere with businesses that use or trade legally in animals.

As the Lacey Act has been enlarged and amended, it has become more controversial, challenged many times in judicial appeals. While most Americans endorse the protection of wildlife, they are less united on the law’s use for plants, particularly for commercial wood. Recently, raids on the Gibson Guitar Company for their presumed illegal use of endangered wood raised the specter that the Lacey Act was inappropriately used to attack a long-standing American company and their beloved product—the Gibson guitar. Similarly, the flooring company Lumber Liquidators recently paid a $13.15 million fine and received a five-year probationary sentence for use and mislabeling of imported endangered woods, believed to be the largest criminal penalty ever levied through the Lacey Act.

Despite legal challenges and regularly required clarification of how and when the law can be used, the Lacey Act has been the salvation for wildlife within the United States. In his extensive review of the Lacey Act in 1995, legal analyst Robert S. Anderson ended this way:

“Addressing his House colleagues in 1900, Congressman John Lacey said, ‘There is a compensation in the distribution of plants, birds, and animals by the God of nature. Man’s attempt to change and interfere often leads to serious results.’ He acted on these sentiments by introducing a brief statute that created little stir during its initial consideration and remains somewhat obscure, even among environmentalists, almost 100 years later. Though Lacey is rarely ranked with notable conservationists such as John Muir and Aldo Leopold, his legacy remains vibrant and effective today in the form of a law that is arguably our nation’s most effective tool in the fight against an illegal wildlife trade whose size, profitability, and threat to global biodiversity Lacey could probably not have imagined.”

Three cheers for the conservationist of the day, John Lacey!

References:

Anderson, Robert S. 1995. The Lacey Act: America’s Premier Weapon in the Fight against Unlawful Wildlife Trafficking. Public Land and Resources Law Review, 16:29-85. Available at: https://scholarship.law.umt.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1199&context=plrlr. Accessed May 25, 2018.

Larkin, Paul. 2012. The Lacey Act: From Conservation to Criminalization. The Heritage Foundation. Available at: https://www.heritage.org/report/the-lacey-act-conservation-criminalization. Accessed May 25, 2018.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Lacey Act. Available at: https://www.fws.gov/le/pdffiles/Lacey.pdf. Accessed May 25, 2018.

Wisch, Rebecca F. 2003. Overview of the Lacey Act (16 U.S.C. SS3371-3378). Animal Legal & Historical Center, Michigan State University. Available at: https://www.animallaw.info/article/overview-lacey-act-16-usc-ss-3371-3378. Accessed May 25, 2018.