February 22 has been declared Nile Day by the countries that share the Nile River basin. Nile Day commemorates the signing of the 1999 agreement to cooperatively manage the river basin, called the Nile Basin Initiative.

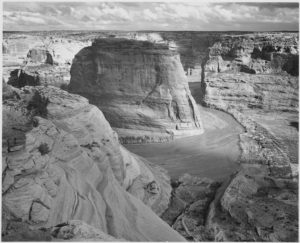

The Nile River is one of the most important waterbodies in the world. By most estimates, it is the longest river in the world, flowing from south to north for 4180 miles. It carries water from the relatively water-rich regions in its upper watershed through the dry regions of The Sudan and then Egypt. Once past Cairo, the river splits into multiple channels, entering the Mediterranean Sea through a broad delta.

The main tributaries are the Blue Nile, which arises in the mountains of Ethiopia, and the White Nile, which flows out of Lake Victoria in Uganda. The Blue and White Niles join to form the Nile River at Khartoum, the capital of The Sudan. About two-thirds of the river’s annual flow comes from the Blue Nile. Adding in the flows from other smaller tributaries, approximately 90% of all the water in the Nile originates in Ethiopia.

The Nile River’s water has been crucial to the development of the civilizations that flanked its banks, from ancient times to the present. The monuments created by past civilizations—the Pyramids at Giza, the Sphinx, and the tombs of Egyptian kings and queens—are considered among the great wonders of the ancient world.

Today, the wonders of the Nile Basin are more closely tied to the engineering technology of the post-World War 2 era. Complementing other smaller dams and irrigation structures, the Aswan High Dam was completed on the river in 1970. The dam created Lake Nasser, which stretches 300 miles south from the dam, crossing the border from Egypt to The Sudan. The dam provides hydro-electricity throughout Egypt. Lake Nasser allows flood water to be stored both for use during the hot, dry parts of every year, but also from one year to the next, counteracting the impacts of both floods and droughts. A second major dam has recently been completed on the Blue Nile by the nation of Ethioplia. The dam, named the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), will provide massive amounts of hydro-electricity and allow similar water-storage capabilities as the Aswan High Dam farther downstream. However, both Egypt and Sudan view the creation of GERD as a threat to their management of the downstream regions of the Nile River, including their ability to generate power and control water storage to prevent floods and droughts. Although the three countries signed a “declaration of principles” in 2015, they remain at odds over the new dam.

Eleven African nations (Burundi, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, South Sudan, The Sudan, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda) share part of the Nile River basin. Because the river is so important to the livelihoods of all, ten of the countries banded together by creating the Nile Basin Initiative in 1999 (Eritrea participates as an observer). The Initiative has the stated vision “to achieve sustainable socio-economic development through the equitable utilization of, and benefit from, the common Nile Basin water resources.” The Initiative is headed by a committee of the water ministers of the member countries; its headquarters is in Entebbe, Uganda.

Nile Day moves among the members countries from year to year. Billed as an event to increase awareness of the Nile River’s importance, events bring together representatives from throughout the basin to develop strategies for enhancing the sustainability of the basin’s environment. The first Nile Day was held in 2007.

References:

Al-Anani, Khalil. 2022. The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam: Limited Options for a Resolution. Arab Center of Washington DC, Sept 16, 2022. Available at: https://arabcenterdc.org/resource/the-grand-ethiopian-renaissance-dam-limited-options-for-a-resolution/. Accessed February 10, 2023.

New World Encyclopedia. Nile River. Available at: http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Nile_River. Accessed February 21, 2017.

Nile Basin Initiative. Nile Day Celebration, 22nd February 2017. Available at: http://www.nilebasin.org/index.php/media-center/documents-publications/48-regional-nile-day-2017-flyer/file. Accessed February 21, 2017.

Nile Basin Initiative. Available at: http://www.nilebasin.org/. Accessed February 21, 2017.