The world’s first national park, Yellowstone, was established on March 1, 1872, when President Ulysses Grant added his signature to the Yellowstone National Park Protection Act. The creation of Yellowstone was a revolutionary event. During a time of western colonization, the practice of the federal government was to give land away, or sell it, so that it could be used for productive processes—mining, farming, lumbering, cattle grazing and the like. To set aside a piece of land this size required the location to be extraordinarily special.

And it was—and remains so today. The park covers a huge land area, totaling nearly 3500 square miles, bigger than both Rhode Island and Delaware—combined. The vast majority lies in Wyoming, with slivers running into Montana and Idaho. Because of its immense size and long period of protection, Yellowstone is considered the northern hemisphere’s best preserved natural ecosystem. Management today recognizes that value, and natural processes—including fire and wildlife population fluctuations—are allowed to occur without restraint as fully as possible.

But what makes Yellowstone unique are its thermal features. The park contains the world’s largest active volcanic caldera, measuring 30 by 45 miles. It has more than 10,000 geothermal surface features, about half of all found in the world. Geysers—of which Old Faithful is the most famous, and not particularly faithful—number more than 500, again more than half of the world’s total. The park experiences as many as 3,000 earthquakes every year, obviously most not large enough to be felt by visitors.

The wildlife of Yellowstone is also spectacular. The mammal diversity is high, with 67 native species, and 285 bird species live in the wide range of environments in the park. The park contains the only continuously free-ranging American bison population still in existence, attracting visitors to the Hayden Valley where the largest herds graze.

Two species are symbolic for the park, as well as controversial. Grizzly bears are a favorite species. Before 1975, the bears were treated much like pets, as visitors fed them from their cars and campgrounds and used the bears as photographic props. Since 1975, when grizzly bears were added to the Endangered Species list, they have been managed as natural residents of the park. Feeding and other casual contact have been outlawed, and people have been removed from prime bear habitat. As a consequence, grizzly bears have increased in abundance. Although the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service believes the bears should be removed from the Endangered Species list, a federal judge has ruled that they remain imperiled and will remain on the list, as of September, 2018.

Similar trends have occurred for Yellowstone’s other symbol—the gray wolf. Wolves had been eliminated from the park in the early 1900s, but after being added to the Endangered Species list in the 1970s, a restoration process began. The first strategy was stocking wolves from Canadian packs. The successful restoration efforts have led to the total recovery of wolf populations, with more than a dozen packs now occupying the park. They are no longer on the Endangered Species list. Some people object to the restoration of wolves, citing their predation on cattle and elk outside the park.

Most people, however, love what has happened to restore and preserve Yellowstone. Annual visitation now tops 4 million people, making Yellowstone one of the top five destinations for national park enthusiasts. Expect big crowds in July, though, as more than 30,000 people each day descend onto the park’s roads and picnic grounds.

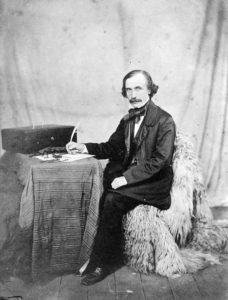

We take for granted today the level of care and management that Yellowstone receives, but the park didn’t start that way. The park’s first superintendent, Nathaniel Langford, was unpaid and had neither a budget nor staff to help him. Eventually Congress balked at the government’s inability to manage the park, and they turned it over to the U.S. Army in 1886. Army troops patrolled the park on horseback, guarding the major attractions and expelling poachers. Not until the National Park Service was created in 1916 did the job of managing the park revert to a civilian workforce(learn more about the NPS here) . Today that workforce includes more than 300 permanent and 400 seasonal employees, dedicated to preserving one of the world’s great natural treasures.

References:

National Park Service, Yellowstone National Park. Birth of a National Park. Available at: https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/historyculture/yellowstoneestablishment.htm.

National Park Service, Yellowstone National Park. Park Facts. Available at: https://www.nps.gov/yell/planyourvisit/parkfacts.htm.

UNESCO. World Heritage list: Yellowstone National Park. Available at: http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/28.

Yellowstone National Park. Grizzly Bears & the Endangered Species Act. Available at: https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/nature/bearesa.htm.