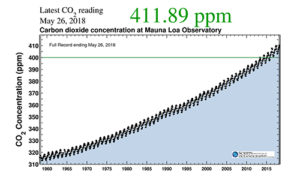

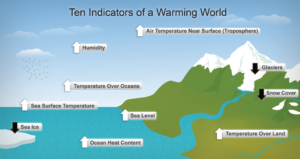

The vast majority of the world’s governments and people now understand that the world’s climate is changing and that the changes are largely caused by human-based emissions of carbon dioxide and other gases into the environment. Getting to this point of understanding, however, has required a major global—and national—commitment to scientific research and education. That research was assured when the United States passed the Global Climate Change Research Act in 1990.

Rancor about the extent and causes of climate change was bitter in the late 1980s. The U.S. Congress and the agencies of the executive branch debated the state of change as well as who should be developing both knowledge and policy. During 1989, President George H. W. Bush advanced progress by asking for a report on the status of climate change in the U.S. Congress chose to go farther, passing a law that made a climate change research program permanent and mandating a regular report on climate change to be produced at least every four years. The Senate passed the bill 100-0 and the House of Representatives passed it by voice vote (meaning no record of the actual votes took place, recognizing overwhelming support for the bill). President Bush signed the bill into law on November 16, 1990. The law has not been amended since it first passed.

The bill requires that the relevant government agencies work together, along with universities, states, industry and other groups, under the direction of a Committee on Earth and Environmental Sciences. The Committee is required to develop a national plan for climate change research, assess the state of the climate, represent the United States in international forums and collaborations on climate change, and report regularly to Congress and the American people.

The most recently available report is from 2014 (which means a new report is required in 2018, some of which is available now and some not). As the report notes, it is “the result of a three-year analytical effort by a team of over 300 experts, overseen by a broadly constituted Federal Advisory Committee of 60 members.” The report highlights 12 findings, which I have paraphrased here:

- Global climate change is real and caused by humans, predominantly by burning fossil fuels.

- Extreme weather events have become more common and are linked to climate change.

- More climate change will occur, especially if we keep burning fossil fuels at today’s rates.

- Impacts of climate change are occurring now and will get more disruptive.

- Climate change threatens human health and well-being in many ways.

- Infrastructure is being damaged now by climate change and the damage will get worse.

- Water quality and quantity are especially affected by climate change.

- Agriculture is suffering from climate change and the damage will get worse.

- Climate change disproportionately impacts Indigenous Peoples.

- Ecosystem services are damaged by climate change.

- Ocean waters are changing in a variety of ways due to climate change.

- We’re starting to adapt to climate change, but our efforts are broadly insufficient.

One of the benefits of passing a law is that it cannot be changed by a member of the executive branch, be it the president or cabinet secretary. Consequently, the government’s work to assess climate change, provide scientific information to the public, and advise the government on policy will continue, regardless of what the climate might be like in Washington!

References:

GlobalChange.gov. Legal Mandate. U.S. Global Change Research Program. Available at: https://www.globalchange.gov/about/legal-mandate#Short%20Title%20Main. Accessed October 27, 2018.

Govtrack. S. 169(101st): Global Change Research Act of 1990. Available at: https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/101/s169. Accessed October 27, 2018.

Melillo, Jerry M., Terese (T.C.) Richmond, and Gary W. Yohe, Eds., 2014: Highlights of Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program. Available at: http://s3.amazonaws.com/nca2014/low/NCA3_Highlights_LowRes.pdf?download=1. Accessed October 27, 2018.

Pielke, Roger A. Jr. 2000. Policy history of the US Global Change Research Program: Part II. Legislative process. Global Environmental Change 10 (2000):133-144. Available at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.529.8677&rep=rep1&type=pdf. Accessed October 27, 2018.