Stewart Udall, Secretary of the Interior under Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, was born on January 31, 1920 (died 2010). Udall is considered one of the most effective leaders of the nation’s primary land management agency during the environmentally active years of the 1960s and 1970s.

Udall came from a family with long roots in Arizona politics and public service. His grandfather served in the Arizona Territorial legislature before statehood in 1912; his father was an Arizona Supreme Court Justice; his younger brother, Morris (popularly known as “Mo”) was a congressional representative and ran for president in 1976.

Udall kept up the family traditions. He served two years as a Mormon missionary before enlisting in the U.S. Army Air Force during World War II, where he served as a gunner on a B-24 bomber. He and brother Mo formed a law firm after the war, through which they worked for desegregation in schools and other public facilities in Arizona. He served three terms in the U.S. Congress.

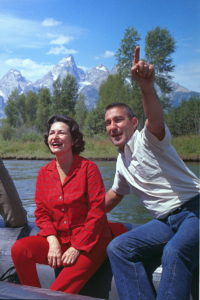

His national impact began when President Kennedy appointed him as Secretary of the Interior in early 1961, a position he held for nine years, serving also under President Johnson. Although he and President Johnson supposedly had a rocky relationship, he was a close colleague of the First Lady, Lady Bird Johnson, working with her on her platform to beautify America (learn more about her here) . He was an outspoken advocate for strong federal land conservation policies, including the acquisition of lands for parks and other conservation purposes. During his term as Secretary, he led the acquisition and reservation of nearly 4 million acres of federal lands, including 4 national parks, 9 national recreation areas, 20 historic sites, 8 national seashores and lakeshores, and more than 50 national wildlife refuges.

He also led the enactment of several new laws that facilitated the further development of federal conservation lands. He helped win passage of the Wilderness Act of 1964, the law that provided formal definition of wilderness and initially designated more than 9 million acres as federally protected wilderness (learn more about the Wilderness Act here). He similarly aided the National Wild and Scenic River Acts of 1968 that extended environmental protection to river systems, now including nearly 13,000 miles of 208 rivers in 40 states. Perhaps most important, however, was the creation of the Land and Water Conservation Fund Act, established by Congress in 1964. The law provided funds for the acquisition of conservation lands, using revenue from sale of excess federal property, federal gas taxes on motor boat fuels and federal taxes on offshore oil leases, along with general appropriations. The act funded federal actions, but also included grants to states for similar actions. Funds available have varied substantially over time, but reached nearly $1 billion in the late 1990s-early 2000s.

Udall believed that outdoor recreation was both healthy and therapeutic. His physical prowess was notable. He was an all-conference guard on the University of Arizona’s basketball team. He climbed both Mount Kilimanjaro and Mount Fuji, and he often led extended hikes, up to 50 miles, while serving as Secretary of Interior. At age 84, he hiked from the bottom to the rim of the Grand Canyon.

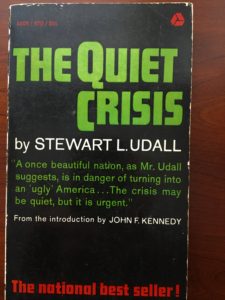

He brought the issue of conservation to the nation’s conscience in 1963 with his book, The Quiet Crisis. The book extolled the essential connection between the land and the American people, and it encouraged Americans to look past short-sighted economic exploitation of the land toward a longer-term approach that we today call sustainability.

References:

American National Biography Online. Stewart Lee Udall. Available at: http://www.anb.org/articles/07/07-00863.html. Accessed January 30, 2017.

National Park Service. Land and Water Conservation Fund. Available at: https://www.nps.gov/subjects/lwcf/index.htm. Accessed January 30, 2017.

Schneider, Keith and Cornelia Dean. 2010. Stewart L. Udall, Conservationist in Kennedy and Johnson Cabinets, dies at 90. New York Times, March 20, 2010. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/21/nyregion/21udall.html. Accessed January 30, 2017.

University of Arizona Library, Special Collections. Stewart Lee Udall: Advocate for the Planet Earth. Available at: http://www.library.arizona.edu/exhibits/sludall/index.html. Accessed January 30, 2017.