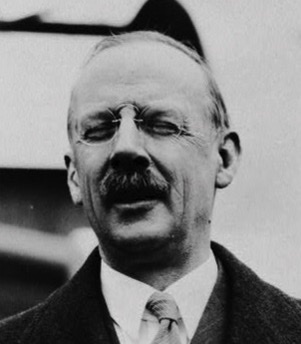

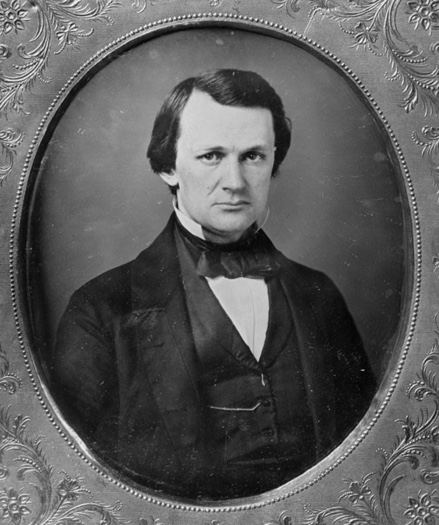

A common question in the conservation community is this: Who was our finest conservation president? Teddy Roosevelt always wins and his nephew, Franklin Roosevelt, usually comes in second. Then there are arguments about Richard Nixon and Jimmy Carter, perhaps Abraham Lincoln. But it is easy to argue that near the top of the list should come Lyndon Baines Johnson, the 36th president of the United States.

Johnson held office from 1963 to 1969, during the height of the growing environmental movement. He understood and believed the message being delivered: Along with prosperity, America wanted a place to live that was safe and beautiful. He was born in a small farming community in Texas and, over his life, he watched the country change from a mostly rural, agricultural economy to a mostly urban, industrialized economy. Along with his wife, Lady Bird, he lamented the ugliness that could accompany that change, and he vowed to help clean up the mess and preserve what was left (learn more about the first lady here).

As president, Johnson approved more than 300 conservation measures. The measures covered virtually all aspects of conservation, including air and water pollution, park and natural area preservation, biodiversity conservation, landscape beautification and urban environmental quality. He created 50 new national park units. He signed laws that established the National Trails and Wild and Scenic Rivers Systems.

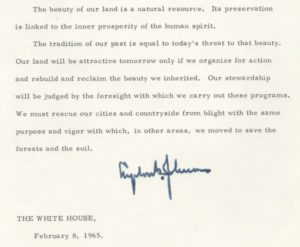

He spoke about the need for conservation many times. One of the most important was his “Special Message to the Congress on Conservation and Restoration of Natural Beauty” on February 8, 1965. Following are a few excerpts from that speech.

“For centuries Americans have drawn strength and inspiration from the beauty of our country. It would be a neglectful generation indeed, indifferent alike to the judgment of history and the command of principle, which failed to preserve and extend such a heritage for its descendants.”

“To deal with these new problems will require a new conservation. We must not only protect the countryside and save it from destruction, we must restore what has been destroyed and salvage the beauty and charm of our cities. Our conservation must be not just the classic conservation of protection and development, but a creative conservation of restoration and innovation. Its concern is not with nature alone, but with the total relation between man and the world around him. Its object is not just man’s welfare but the dignity of man’s spirit.”

“I have already proposed full funding of the Land and Water Conservation Fund, and directed the Secretary of the Interior to give priority attention to serving the needs of our growing urban population.”

“The 28 million acres of land presently held and used by our Armed Services is an important part of our public estate. Many thousands of these acres will soon become surplus to military needs. Much of this land has great potential for outdoor recreation, wildlife, and conservation uses consistent with military requirements. This potential must be realized through the fullest application of multiple-use principles.”

“Air pollution is no longer confined to isolated places. This generation has altered the composition of the atmosphere on a global scale through radioactive materials and a steady increase in carbon dioxide from the burning of fossil fuels. Entire regional airsheds, crop plant environments, and river basins are heavy with noxious materials.”

“The beauty of our land is a natural resource. Its preservation is linked to the inner prosperity of the human spirit. The tradition of our past is equal to today’s threat to that beauty. Our land will be attractive tomorrow only if we organize for action and rebuild and reclaim the beauty we inherited. Our stewardship will be judged by the foresight with which we carry out these programs. We must rescue our cities and countryside from blight with the same purpose and vigor with which, in other areas, we moved to save the forests and the soil.”

References:

Association of Centers for the Study of Congress. President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Natural Beauty Message. Available at: http://acsc.lib.udel.edu/items/show/292. Accessed February 5, 2018.

Johnson, Lyndon B. 1965. Special Message to the Congress on Conservation and Restoration of Natural Beauty. The American Presidency Project. Available at: http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=27285. Accessed February 5, 2018.

National Park Serivce. Lyndon B. Johnson and the Environment. Available at: https://www.nps.gov/lyjo/planyourvisit/upload/EnvironmentCS2.pdf. Accessed February 5, 2018.