A favorite trivia question is, what does “scuba” stand for? The answer, of course, is self-contained underwater breathing apparatus. A much better question would be who was the famous co-inventor of scuba? The answer is the same as the answer to the question who’s the most famous ocean explorer? Right, Jacques Cousteau.

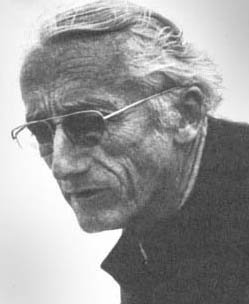

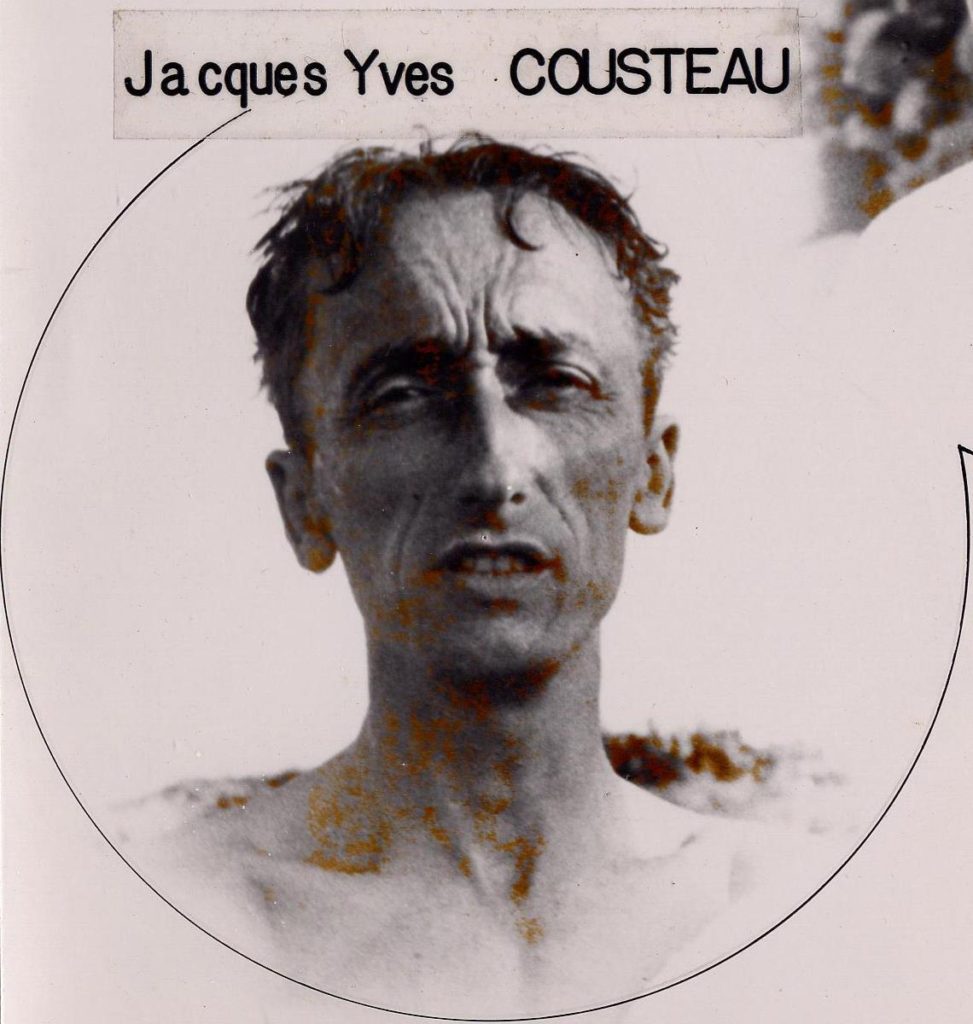

Jacques-Yves Cousteau was born on June 11, 1910, in a small town near Bordeaux, France (died 1997). Although he was anemic and sickly as a child, he learned to swim at an early age. He said, “I loved touching water. Physically. Sensually. Water fascinated me.” Not surprisingly, he enlisted in the French navy. His attraction was to the air, however, not the water—he trained to be a navy pilot. But a traffic accident near the end of his training broke both his arms, ending his dreams to fly. He swam daily in the Mediterranean as physical therapy for his arms, and when, in 1936, a friend loaned him a pair of goggles for his swim, he saw his future clearly: ”Rocks covered with green, brown and silver forests of algae and fishes unknown to me, swimming in crystalline water. Sometimes we are lucky enough to know that our lives have been changed, to discard the old, embrace the new, and run headlong down an immutable course. It happened to me on that summer’s day, when my eyes were opened on the sea.”

World War II delayed his sea adventures for a time. He was a gunnery officer for the Navy and later served as a spy in Italy for the French Resistance (his heroics earned him the Legion of Honour Award from the French people). As the war ended, he convinced the navy to let him lead an Undersea Research Group that swept harbors and shipping lanes for mine.

In 1943, he began working with an engineer, Emile Gagnan, to free divers from heavy, constraining, and surfaced-tethered diving gear. Compressed air-tanks had been perfected for wartime use, with one-way valves to control air flow. Cousteau and Gagnan adapted the tanks for underwater use, patenting the “Aqua-lung,” that we now call scuba, in 1946. They also invented a waterproof case for cameras that could descend hundreds of feet.

Armed with an Aqua-lung and movie camera, Cousteau began the work for which he became famous. Although not trained as an oceanographer, he explored the world’s oceans with the eyes of both a scientist and an artist. He became, as eulogized at his death, “the Rachel Carson of the oceans.” His first book, The Silent World, published in 1953, sold more than 5 million copies and has been translated into 22 languages. A movie of the same name expanded his fame—and public appreciation of the oceans—even more. He renovated a World War 2 minesweeper into an oceanographic research vessel that he named Calypso and sailed to all corners of the world’s oceans. He made 120 documentaries about the ocean (including 9 seasons of the U.S. based “The Undersea World of Jacque Cousteau”), wrote more than 50 books, received several Oscars and the Palm d’Or. He was a “popularizer of genius.”

During his long career, Cousteau’s accomplishments went well beyond producing movies and publishing books. He headed Monaco’s Oceanographic Institute for more than 30 years. His early work with scuba demonstrated its utility for salvaging ancient artifacts, establishing the field of underwater archeology. He invented the aqua-disk, a one-person submarine. He experimented with long-term underwater habitation, in both shallow and deep water.

He used his mastery of mass media to spread the need for conservation of the oceans and the earth as a whole. In 1974, he founded the Cousteau Society, a U.S.-based non-profit group dedicated to “the protection and improvement of the quality of life for present and future generations.” He considered himself not an “ecologist for the animals,” but “an ecologist for people.” He was outspoken about what he felt were the fundamental problems facing our future. “You see a beer can and you pick it up. You think you’ve done a great thing for the environment….But these are just symptoms of our sickness….It is the economic system that confuses price and value. This confusion causes us to hurt and deplete our natural resources and damage the environment we are living in.”

Cousteau lived by a principle that drove him for all his 87 years on earth. In English it reads, “We must go and see for ourselves.” He went everywhere to see for himself, especially to the depths of the oceans. As John Denver sang in his elegy to Cousteau, Calypso, “Aye Calypso the places you’ve been to; The things that you’ve shown us; The stories you tell; Aye Calypso, I sing to your spirit….” (learn more about John Denver here). May I suggest that we follow Cousteau’s example—and go see a bit of the outdoors, today!

References:

Cousteau Society. About the Cousteau Society. Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20090122055053/http://cousteau.org/about.html. Accessed February 24, 2020.

Encyclopedia Britannica. Jacques Cousteau, French Ocean Explorer and Engineer. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/technology/transportation-technology. Accessed February 24, 2020.

Kraft, Scott. 1995. Lose Angeles Times Interview: Jacques Cousteau: A Lifetime Spent Fighting for the Environment. Los Angeles Times, Oct. 1, 1995. Available at: https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1995-10-01-op-52539-story.html.

Accessed February 24, 2020.

Jonas, Gerald. 1997. Jacques Cousteau, Oceans’ Impressario, Dies. The New York times, June 26, 1997. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/1997/06/26/world/jacques-cousteau-oceans-impresario-dies.html. Accessed February 24, 2020.

Sea and Sky. Meet the Ocean Explorers – Jacques Cousteau. Available at: http://www.seasky.org/ocean-exploration/ocean-explorers-jacques-cousteau.html. Accessed February 24, 2020.