The National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty was incorporated on January 12, 1895. It has become the largest and most influential preservation organization in England, in a sense the British equivalent of the U.S. National Park Service. According to the Trust’s 2020-21 annual report, the trust protects 780 miles of coastline, 250,000 hectares of land (1.5% of the entire land surface of England), more than 500 properties (structures and nature preserves), and nearly 1 million catalogued historical artifacts. The Trust’s properties hosted more than 20 million visits during the year.

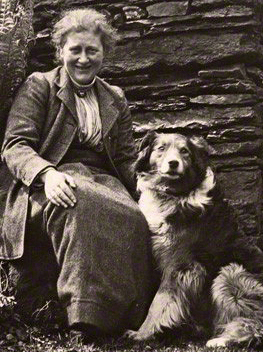

The National Trust owes its existence to the efforts of Octavia Hill, a pioneering social reformer of the late Nineteenth Century. Hill came from a family of advocates for the poor, and she followed in their footsteps. On behalf of fellow reformer John Ruskin, she managed a set of broken-down tenements in what is now the Marylebone section of London, where she rented to poor women and also provided them with job training, actual jobs and cultural exposure. By the 1870s, she housed and watched over the social development of 3,000 tenants.

But she also realized that the poor needed parks and open spaces. Actually, she understood that everyone needed such spaces, and that they were fast disappearing as London developed. She reasoned that “a few acres where the hill top enables the Londoner to rise above the smoke, to feel a refreshing air for a little time and to see the sun setting in coloured glory which abounds so in the Earth God made” was a tonic for the harried life of the salesperson as well as the foundry or textile worker. And she particularly abhorred the reality that city parks were becoming increasingly gated, available only to those who could afford to live around their perimeters. One of her first projects was to stop a portion of Hampstead Heath, the renowned London park, from being developed.

So, together with colleagues Sir Robert Hunter and Hardwicke Rawnsley, she organized the National Trust as a public charity. The trust’s purpose was to “promote the permanent preservation for the benefit of the Nation of lands and tenements (including buildings) of beauty or historic interest.” Anyone who has visited a park or country estate in England owes much to the passion and persistence of Olivia Hill.

References:

National Trust. 2021. National Trust annual report 2020/2021. Available at: http://www.nationaltrustannualreport.org.uk/. Accessed January 9, 2023.

YMCA George Williams College. Octavia Hill, housing and social reform. Available at: http://infed.org/mobi/octavia-hill-housing-and-social-reform/. Accessed January 11, 2017.