Tigers are in trouble. The numbers of this charismatic species have declined by more than 95% in a century. Whether or not the species can survive remains in doubt. So, the participants at a tiger conservation summit in St. Petersburg, Russia, in 2010 decided that the tiger needed its own day to raise awareness of the animal’s plight. Since then, International Tiger Day has been held each July 29.

The tiger (Panthera tigris) is the world’s largest cat, with males weighing up to 700 pounds. Tigers are classified in a single species, but with six genetically distinct subspecies across its large range (taxonomists seem to be squabbling about this). They are primarily solitary, maintaining large home ranges to provide sufficient prey for an appetite that can consume 80 pounds in one meal. Tigers live up to 20 years in the wild, becoming reproductively mature in 4-5 years. Females have 2-4 cubs every other year.

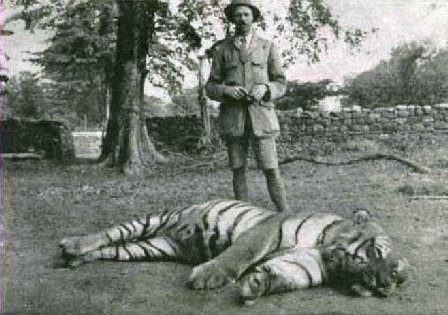

Before humans started changing things, tigers lived throughout a huge range—in far eastern Russia, throughout southeastern Asia and in Malaysia. Today, wild tigers inhabit only 7% of that former range, almost all in protected preserves. About 70% of all wild tigers live in India; the other 30% are scattered among 12 other nations. A century ago, as many as 100,000 tigers roamed freely, but today the population is about 4,000. Multiple factors have impacted tigers—trophy harvest, habitat conversion, human-animal conflict, harvest for traditional medicines, and illegal poaching. Ground tiger bone sells for as much as $115 per pound. The combination of all these forces has led IUCN to classify the tiger as an “endangered species,” and CITES to place it on its Appendix I (no international trade).

Conservation efforts have expanded since the 2010 tiger summit. A goal was set then to double the world population of wild tigers—to 6,000 individuals—by 2022, the next Chinese Year of the Tiger. The chosen strategy is an integrated habitat conservation program working across nations, organizations and local communities. The biggest success has come from India, where the government has created 50 tiger reserves and whose tiger population has grown to 3,000. Because populations in those reserves are growing, which forces some individuals into non-protected lands, the government is also working to create habitat corridors between reserves. With a total worldwide population of about 4,000 wild tigers in 2020, however, reaching the goal of 6,000 by 2022 seems unlikely.

Conservationists are quick to point out that saving tigers accomplishes so much more than just keeping one species—albeit a beautiful and meaningful one—alive. Tigers are umbrella species, meaning that protecting their habitat protects a wide range of plants and animals that share their same ecosystem. Tigers are also top predators, playing an important role in structuring the trophic levels below them.

But perhaps it is enough to want to save tigers because they are, well, just tigers.

References:

BBC News. 2019. India tiger census shows rapid population growth. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-49148174. Accessed April 3, 2020.

IUCN. 2019. International Tiger Day: Celebrating an integrated approach for tiger conservation. Available at: https://www.iucn.org/news/species/201907/international-tiger-day-celebrating-integrated-approach-tiger-conservation. Accessed April 3, 2020.

IUCN. Red List – Tiger Panthera tigris. Available at: https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/15955/50659951#taxonomy. Accessed April 3, 2020.

US Fish and Wildlife Service. Tigers. Available at: https://www.fws.gov/international/animals/tigers.html. Accessed April 3, 2020.

World Wildlife Fund. Species—Tiger, Facts. Available at: https://www.worldwildlife.org/species/tiger. Accessed April 3, 2020.