On September 15, 1835, H.M.S. Beagle sighted land and dropped anchor at the Galapagos Islands. The naturalist on board, Charles Darwin, started collecting specimens and taking notes—and the science of evolution and ecology began its own evolution in his brain. Neither the islands nor the world would ever be the same again.

Captain Robert FitzRoy was in command of the Beagle, leading it on a five-year voyage to chart the coast of South America. He had invited on board a young gentleman to be his companion and to serve as the voyage’s naturalist. Charles Darwin was 22 when the journey began, a mere 26 when he landed at the Galapagos.

Darwin explored the islands for 35 days as Captain FitzRoy cruised the archipelago making charts of its shorelines, natural harbors and navigational dangers. When he arrived, Darwin was most intrigued by the volcanoes of the islands, but he collected and studied the flora and fauna as well. “I dutifully collected all the animals, plants, insects, & reptiles from this Island,” he wrote about his visit to the island Floreana.

As he explored the living species of the islands, two groups gave him cause to wonder about the immutability of life. One was the mockingbirds. Darwin noted that mockingbirds from different islands looked different, assigning them to three different species. The second was the giant tortoises. The tortoises from different islands looked different as well, a fact related to him by the vice-governor of the islands, who claimed that by the peculiar and distinctive shapes of their shells, “he could at once tell from which island any one was brought.” (Although the tortoises were impressive, the major impact they made was on the explorers’ diets—tortoises were more valuable as roasted meat and soup than as biological specimens!)

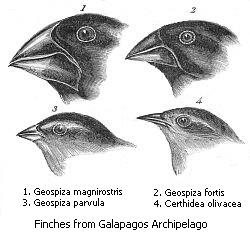

It took a long time for the impact of the Galapagos biodiversity to make its full impact on Darwin—the visit included no “ah ha!” moment. The Beagle left the islands on October 17, and Darwin spent the long homeward voyage preparing specimens and completing his notebooks. When he returned to London, he turned over his bird collection to the accomplished ornithologist and artist John Gould. Gould discovered that Darwin had misclassified a large array of specimens as minor variants of known species, when in fact they were new species of finches that had radiated to fill ecological niches available on the islands. The now-famous “Darwin’s finches” took on special meaning to Darwin when examined in this way, influencing his continuing development of the ideas of variation and natural selection.

When he finally got around to publishing his masterpiece, On the Origin of Species, in 1859, the role of his observations on the Galapagos was apparent:

“The relations just discussed … [including] the very close relation of the distinct species which inhabit the islets of the same archipelago, and especially the striking relation of the inhabitants of each whole archipelago or island to those of the nearest mainland, are, I think, utterly inexplicable on the ordinary view of the independent creation of each species, but are explicable on the view of colonisation from the nearest and readiest source, together with the subsequent modification and better adaptation of the colonists to their new homes.”

References:

Darwin Online. Darwin’s field notes on the Galapagos: ‘A little word within itself.’ Available at: http://darwin-online.org.uk/EditorialIntroductions/Chancellor_Keynes_Galapagos.html. Accessed September 14, 2017.

Galapagos Conservancy. Charles Darwin. Available at: https://www.galapagos.org/about_galapagos/about-galapagos/history/human-discovery/charles-darwin/. Accessed September 14, 2017.

Sulloway, Frank J. 2005. The Evolution of Charles Darwin. Smithsonian Magazine, December 2005. Available at: http://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/the-evolution-of-charles-darwin-110234034/. Accessed September 14, 2017.