She was an African-American opera singer who thrilled European audiences in the 1950s. But to most in her adopted home on Amelia Island, Florida, she was just the “Beach Lady.” The lives of music lovers and environmentalists all benefitted from her untiring passion and persistence.

MaVynee Oshun Betsch was born in Jacksonville, Florida, on January 13, 1935. Her family was part of the African-American elite of Jacksonville. Her great-grandfather was Abraham Lincoln Lewis, owner of the Afro American Insurance Company, which he founded in 1901. Lewis was one of the successful businessmen who built the African-American community of Jacksonville, a parallel universe required by the Jim Crow laws that mandated segregation in many southern states.

Coming from a wealthy and cultured family, Betsch had the opportunity to study music at Oberlin Conservatory of Music in Ohio. After graduating in 1955 with majors in voice and piano, she moved to Europe and studied voice in Paris and London. She toured Europe as an opera singer for seven years, singing mostly for German audiences.

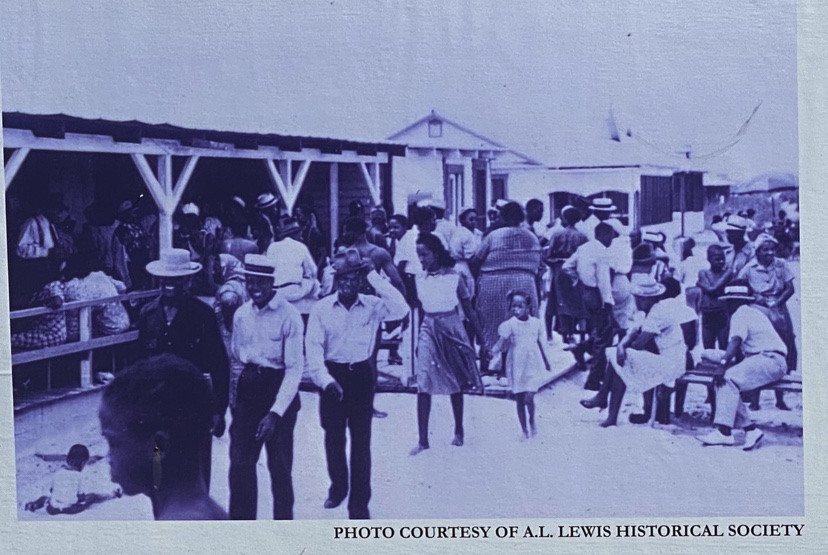

In the year she was born, her great grandfather made a daring business and social investment. Using the Pension Bureau of his insurance company, Lewis bought 33 acres of Amelia Island waterfront and established the community of American Beach. Later he bought more acreage, expanding American Beach to 216 acres. His idea was to make a place where African-Americans could enjoy the beach—a place for “recreation and relaxation without humiliation.”

American Beach became a destination for African-American vacationers from across the country. There they could enjoy an outdoor experience without worry of the harassment and violence of the Jim Crow era. American Beach became the place to go. The waterfront pavilion welcomed the nation’s most prominent African-American entertainers, including Cab Calloway, Ray Charles and Duke Ellington.

In the mid-1960s, the prominence of American Beach began to decline. With the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, segregation was outlawed. African-Americans began vacationing at other beach locations, from Miami to Atlantic City. Also in 1964, Hurricane Dora tore through the community, destroying homes and businesses, many of which never recovered.

About this time, Betsch tired of the diva’s life and returned home. She loved American Beach and, from 1975 onwards, made its preservation her life’s work. She also understood that places like American Beach, a natural haven in an industrializing world, were necessary everywhere. She became a dedicated environmentalist, donating her entire fortune, estimated at $750,000, to environmental causes.

She was not only dedicated, but also somewhat eccentric. She gave up her home and began living on the beach, spending her days sitting in a lawn chair and telling her story to passers-by. She grew her hair long—seven feet long and gathered in a huge bun atop her head and draped over her arm—to demonstrate that nature didn’t need help to grow beautiful things. She grew the fingernails on her left hand to prove the same point, the nails making an 18-inch spiral at one point. Her clothes were covered in political buttons that espoused her commitment to the environment and social justice. She especially appealed to children: “They come to see my hair, and I give ‘em a little history.”

Her efforts for conservation have paid off. A portion of American Beach is the NaNa sand dune, the tallest in Florida. Because of her persistent efforts, the development company that owned the dune transferred it to the National Park Service and it is now preserved as part of the Timucuan Ecological & Historical Preserve. Another of her dreams was to create a center to tell the natural and human history of American Beach—so future generations would understand the Jim Crow era and what it meant to the lives of African-Americans. That dream became reality in 2014, when the American Beach Museum opened.

MaVynee Betsch died from cancer in 2005. She was a unique person, without question, who made significant contributions to conservation. But she is not widely known, illustrating our need to more fully develop and chronicle the diversity of the environmental movement and the contributions of African-Americans to that movement. Had it not been for my conversations with noted African-American environmentalist Carolyn Finney (author of Black Faces, White Spaces), I would not have known to include her in this chronology. But at least one person took note: The Dalai Lama named her an “Unsung Hero of Compassion” just after her death in 2005.

Betsch once left this message on her voicemail: “Hello. This is the Beach Lady. If you’re getting this message, it may be because I have turned into a butterfly and floated out over the sand dune.” And that sand dune remains because the Beach Lady made us keep it!

References:

BlackPast.org. American Beach, Jacksonville, Florida (1936- ). Available at: http://www.blackpast.org/aah/american-beach-jacksonville-florida-1936. Accessed January 12, 2018.

Florida Times-Union. 2005. MaVynee Betsch. Available at: http://www.legacy.com/obituaries/timesunion/obituary.aspx?pid=15022945. Accessed January 12, 2018.

Gullan/Geechee Nation. 2015. The Beach Lady MaVynee Betsch: Gullah/Geechee Sacred Ancestor. Available at: https://gullahgeecheenation.com/2015/01/13/the-beach-lady-mavynee-betsch-gullahgeechee-sacred-ancestor/. Accessed January 12, 2018.

HistoryMakers. MaVynee “Beach Lady” Betsch. Available at: http://www.thehistorymakers.org/biography/mavynee-beach-lady-betsch-39. Accessed January 12, 2018.

National Park Service. Timucuan Ecological & Historic Preserve. Available at: https://www.nps.gov/timu/learn/historyculture/ambch.htm. Accessed January 12, 2018.

Rymer, Russ. 2003. Beach Lady. Smithsonain Magazine, June 2003. Available at: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/beach-lady-84237022/. Accessed January 12, 2018.