It is leap-day, and what better time to celebrate the incredible feats of leaping that some of our natural friends perform.

Let’s start with the obvious, lemmings leaping off cliffs. Bad news: That’s an unfortunate myth. Lemmings are rodents with enormous powers of reproduction. Consequently, every few years their populations grow too large for their current habitat. In response, large groups migrate together in search of a new home. They are good swimmers, and they don’t let obstacles get in the way. But, they don’t launch themselves off cliffs in apparent mass suicides. That myth comes from an old nature film in which the film crew actually pushed lemmings off a cliff for the dramatic effect. Bad behavior by humans, but not by lemmings.

Humans have also engaged in similar behavior to outwit the game animals they used for food, clothing and tools, specifically the American bison. Native peoples living on the plains would herd bison to the edge of a cliff and then drive them over the edge, collecting the dead animals from the base of the cliff. Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump in southwestern Alberta is an UNESCO World Heritage Site devoted to the aboriginal practice conducted there. The site was used for over 600 years, demonstrating the sustainability of traditional, communal hunting techniques.

But let’s talk about leapers that don’t rely on an assist from humans. Mark Twain wrote a famous story about one such leapers—The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County. A competition by the same name goes on to this day. The world champion is Rosie the Ribeter, an American bullfrog, that jumped a total of 21 feet, 5.75 inches in a combined three-leap event in 1986. But the true world record, we’re told, is a South African frog of unknown heritage that jumped more than 33 feet in one leap.

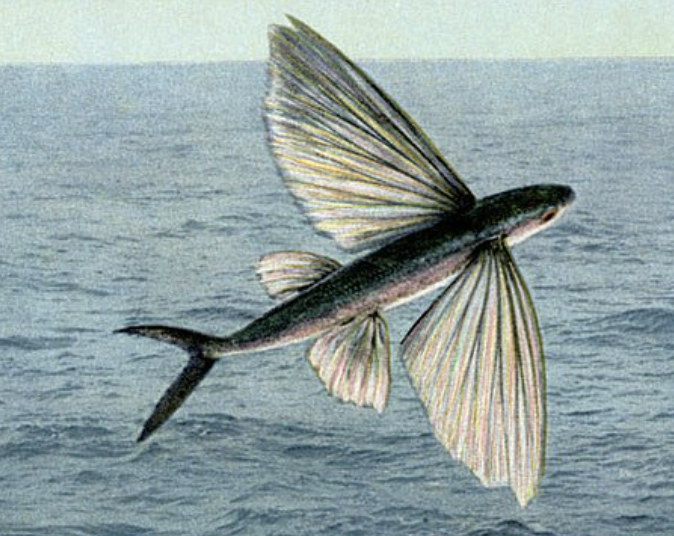

Then there are the flying fishes. Flying fish are a family of more than 40 species that can grow to about 18 inches long. The fish doesn’t actually fly, it leaps. Its streamlined shape allows it to swim fast, explode from the surface and glide along, supported on wing-like pectoral fins. A single leap can go farther than 600 feet, but the fish can extend the flight by falling to the surface, flexing its tail and returning to the air. Extended leaps like this can go farther than 1300 feet.

Among mammals, the champion seems to be the red kangaroo. These 200-pound leapers of Australia move in a series of leaps, with a consistent hop that goes 6 feet high and 25 feet long. But on occasion they can leap much farther, up to 45 feet in a single bound.

The champion of all leapers is, of course, the flea. This tiny insect routinely jumps 5 inches up and 8 inches out. But record flights of fleas are as far as 19 inches, about 300 times its body length. Comparing that to a 6-foot-tall human, that would be a leap of 1800 feet, or about one-third of a mile! Eat your heart out, Spiderman.

References:

Encyclopedia Britannica. Do Lemmings Really Commit Mass Suicide? Available at: https://www.britannica.com/story/do-lemmings-really-commit-mass-suicide. Accessed February 23, 2018.

FleaScience. How far and high can fleas jump? Available at: http://fleascience.com/flea-encyclopedia/life-cycle-of-fleas/adult-fleas/how-do-fleas-move/how-far-and-high-can-fleas-jump/. Accessed February 23, 2018.

Lindsay. 2012. Let the games begin! Amphibian Rescue & Conservation Project. Available at: http://amphibianrescue.org/tag/american-bullfrog/. Accessed February 23, 2018.

National Georgaphic. Flying Fish. Available at: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/fish/group/flying-fish/. Accessed February 23, 2018.

National Geographic. Red Kangaroo. Available at: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/mammals/r/red-kangaroo/. Accessed February 23, 2018.

UNESCO. Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump. Available at: http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/158. Accessed February 23, 2018.