Commercial fishermen first raised the alarm: The oceans were being overfished. They knew it long before anyone else, because they were experiencing smaller catches from each haul of their nets, needed to travel to deeper and more dangerous waters to fill their holds, and caught smaller fish every year.

It took many years and much debate for science and government to agree with the fishermen. Around 1850, government commissions began to look into the claims of fishermen. Some of the most learned men of the time, including Thomas Huxley, insisted the oceans were inexhaustible, based merely on their great size. Others, using data, concluded the opposite.

The U.S. government decided to do something about it in 1871. Congress passed and President Grant signed, on February 9 of that year, a law which created the U.S. Office of the Commissioner of Fish and Fisheries. Its role was to “prosecute investigations on the subject (of the diminution of valuable fishes) with the view to ascertaining whether any and what diminution in the number of the food-fishes of the coast and the lakes of the United States had taken place.” The Fish Commission, as it became known, was also to make recommendations for repairing the fisheries.

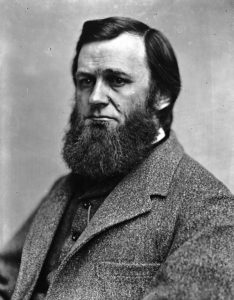

President Grant appointed Spencer Fullerton Baird as Commissioner. At the time, Baird’s full-time job was as the original curator of the Smithsonian Institution, which had been established in 1850 (in 1878, Baird became the second Secretary of the Smithsonian) . A well regarded naturalist, Baird took a broad approach to understanding and improving the country’s fisheries. He established headquarters at Woods Hole, Massachusetts (now one of the world’s leading centers for marine science) . He began studies of major fisheries, including striped bass, cod and bluefish. He invested in aquaculture, which was considered a promising method for growing marine fisheries populations (it later proved not to be particularly useful). Baird directed the agency until his death in 1887, but by then the Fish Commission and its purpose were well established.

Over the past century, the U.S. Fish Commission has seen many re-organizations. It began as an independent agency, then became part of the new Department of Commerce and Labor in 1903, switched to the Department of Interior in 1939 and returned to Commerce in 1970. In that year it was placed inside the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA, where it remains today) and named the National Marine Fisheries Service.

Today, NOAA Fisheries has enormous responsibilities. It oversees regulations governing the catches of all marine fisheries, a $200 billion industry supplying 1.6 million jobs. It implements the Endangered Species Act for 157 marine and anadromous species. It conducts research on fisheries and marine biology through a network of 6 science centers and 20 laboratories. Most importantly, it tracks the status of 474 stocks of fisheries organisms with the goal of assuring the sustainable yield from those stocks.

References:

Guinan, John A. and Ralph E. Curtis. 1971. A Century of Conservation. NOAA(12):40-44. Available at: https://www.nefsc.noaa.gov/history/stories/century.html. Accessed February 6, 2018.

Nielsen, Larry A. 1976. The Evolution of Fisheries Management Philosophy. Marine Fisheries Review December 1976:15-23. Available at: http://spo.nmfs.noaa.gov/mfr3812/mfr38122.pdf. Accessed February 6, 2018.

NOAA Fisheries. About Us. Available at: https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/about-us. Accessed February 6, 2018.

Smithsonian Institution Archives. Spencer Fullerton Baird, 1823-1887. Available at: https://siarchives.si.edu/history/spencer-fullerton-baird.