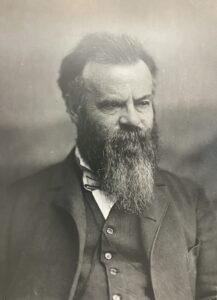

His tombstone in Arlington National Cemetery says simply that John Wesley Powell was a “Soldier, Explorer, Scientist.” Those three words summarize a life that makes Powell one of America’s greatest students of the vast western region of North America.

John Wesley Powell was born on March 24, 1934, in New York State (died 1902). But along with his family, he moved early to farms in Ohio, Wisconsin and Illinois. He was always interested in nature, taking every opportunity to informally study the science he loved. He took expeditions throughout the Midwest, collecting specimens for the Illinois Natural History Survey. At age 22, he rowed the entire length of the Mississippi River, collecting mollusk specimens and other biological and geological artifacts. He followed that expedition by rowing the entire Ohio and Illinois Rivers. Without a college degree, he nonetheless became widely known as an expert naturalist, so much so that in 1859, he was named Secretary of the Illinois Natural History Society, housed at Illinois State Normal University. He was an accomplished explorer and scientist before he turned 30.

But the start of the Civil War put a temporary end to those pursuits—it was time to become a soldier. As a devoted opponent of slavery, he enlisted in the army as a private, was rapidly promoted to lieutenant and served in many battles as an artillery officer. At the Battle of Shiloh, he was shot, resulting in the amputation of his right arm. As soon as possible, he returned to active service, fighting later at Vicksburg. He required another surgery, but returned to fight again, earning the rank of major.

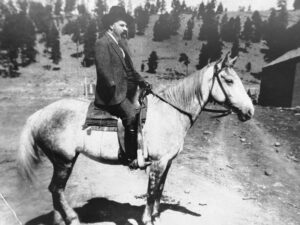

After the war ended, he became a professor of geology at Illinois Wesleyan University, allowing him to visit the western U.S. on field trips. He was mesmerized by the landscape and determined to explore the great unknown regions of the arid southwest.

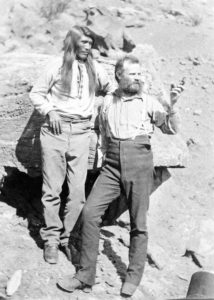

The crowning achievement of his life as an explorer occurred during the summer of 1869. With a crew of ten and four boats, he launched off to explore the entire length of the Colorado River, a feat never before accomplished. For three months, the team ran rapids, portaging around the worst and barely surviving the rest. They ran an estimated 500 significant rapids during the 1000-mile trip. Undaunted by the absence of an arm, Powell climbed mountains without hesitation, recording the geology and topography of the landscape. Reduced to two boats and just six men, the team emerged at the southern end of the Grand Canyon, emaciated but triumphant.

News of the expedition made Powell a national hero, and his chronicle of the journey, in books and lectures, furthered that reputation. He repeated the expedition two years later, this time producing the surveying data that filled in the gaping hole in the U.S. map. Fully understanding the need to document the condition of the West before it could be effectively settled, Powell lobbied successfully for a geological agency in the federal government—the U.S. Geological Survey was established in 1879 and Wesley became its second, but clearly most influential, director from 1881 to 1894. At the same time, he directed a new Bureau of Ethnology at the Smithsonian Institution, devoted largely to Powell’s goal to document the cultures of Native Americans.

Powell had a particular view of the use of the arid West. He believed that it could not be settled like the water-rich eastern states and territories, but rather required a detailed survey of the land and a specific settlement strategy matching the realities of the environment. He also believed that Native Americans were badly misrepresented and their cultures needed documentation and explanation to the rest of the country. Unfortunately, neither of these views could overcome the nation’s drive to colonize the West at the expense of Native American peoples.

Powell died in 1902, and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery, along with his wife, Emma. At the time of his death, he was nearly penniless. But his legacy endures. A news report at that time noted that he was among “the foremost rank of geologists and anthropologists of the world.” And a noted historian wrote that, “No part of Powell’s life is more spectacular than his heroic efforts to preserve the public domain from pillage for private gain.”

References:

Arlington National Cemetery. John Wesley Powell, Major, United States Army. Available at: http://www.arlingtoncemetery.net/jwpowell.htm. Accessed March 20, 2018.

BBC News. 2014. John Wesley Powell: The one-armed explorer. 4 January 2014. Available at: http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-25491932. Accessed March 20, 2018.

Jenkins, Mark Collins. 2018. John Wesley Powell: Soldier, Explorer, Scientist and National Geographic Founder. National Geographic Blog. Available at: https://blog.nationalgeographic.org/2018/01/02/john-wesley-powell-soldier-explorer-scientist-and-national-geographic-founder/. Accessed March 20, 2018.

Powell Museum. The Life of John Wesley Powell. Available at: http://www.powellmuseum.org/museum_powell.php. Accessed March 20, 2018.