For the drought-stricken residents of the Great Plains, Palm Sunday of 1935 seemed like a fresh start. The winds had stopped, the temperature had warmed and the sun was out. It was spring, and perhaps the start of a year when rains would return and life could be normal again.

But by late afternoon, everything had changed. The temperature started falling, 30 degrees in some places. The sun was covered in thick clouds. The wind began blowing, growing in fury by the minute, steady at 60 miles per hour in some locales. And the dust began to blow. A huge dust cloud, hundreds of feet high, hundreds of miles long and black as night descended from the Dakotas to the panhandles of Oklahoma and Texas.

Residents thought the world was ending. Literally. They thought the biblical prediction of Armageddon was upon them. In minutes, the daylight turned to darkness as though it were midnight. You couldn’t see your hand in front of your face. People went blind from the blown dirt. In time, the day—April 14, 1935—became known as Black Sunday, the day of the worst dust storm in the history of the country, perhaps the world. The next day, a reporter wrote an article in which he referred to the area as the “dust bowl,” the name we now associate with a decade-long natural resource disaster.

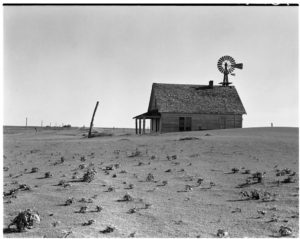

Black Sunday was the result of a particular set of weather conditions that made it extraordinarily bad, but the general situation had become commonplace. Similar storms, but never as bad, had occurred often—14 in 1932, and 38 in 1933. The cause? The Great Plains had been suffering since 1930 in the longest extended drought in its history. Poor farming practices, spurred on by needs to grow more wheat to support the war effort during WW1 and later by land speculation, had reduced the formerly lush prairie to dry, dusty, barren fields.

The result was soil erosion on an unprecedented scale. On Black Sunday alone, 300,000 tons of soil were picked up and blown across the continent. By the end of the decade, 35 million acres of farmland had been totally destroyed and another 125 million acres had been severely impaired. The landscape and its economy were in shreds. More than 2.5 million residents of the Great Plains states abandoned their homes, farms and businesses.

Less than two weeks after Black Sunday, on April 27, 1935, Congress acted to counteract the damage. Congress established the Soil Conservation Service, noting that “the wastage of soil and moisture resources on farm, grazing, and forest lands … is a menace to the national welfare.” Since then, the agency, now called the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), has implemented programs designed to protect soil and retain moisture through restoration programs, watershed management projects and technical assistance and cost-sharing to landowners (see the entry for April 27 for more on the NRCS).

The Dust Bowl had a profound effect on the character of the United States. One of the nation’s greatest novels, The Grapes of Wrath, by John Steinbeck, chronicled the story of farmers displaced by the disaster and the Great Depression. His novel was published on April 14, 1939, exactly four years after Black Sunday. Steinbeck felt his book would not be widely popular, saying, “I’ve done by damndest to rip a reader’s nerves to rags.”

Dorothea Lange was hired as a photographer to chronicle the devastation of the region, a now famous portfolio of documentary photographic art. The great folk song writer and singer, Woody Gutherie, was 22 when the Black Sunday storm rolled through his home in Pampa, Texas. He wrote the song, “So Long, It’s Been Good To Know Yuh,’” about the storm. His lyrics include the following:

“A dust storm hit, an’ it hit like thunder;

It dusted us over, an’ it covered us under;

Blocked out the traffic an’ blocked out the sun,

Straight for home all the people did run,

Singin’:

So long, it’s been good to know yuh;

So long, it’s been good to know yuh;

So long, it’s been good to know yuh.

This dusty old dust is a-getting’ my home,

And I got to be driftin’ along.”

References:

Blakemore, Erin. 2017. Black Sunday: The Storm That Gave Us the Dust Bowl. Mental Floss, January 18, 2017. Available at: http://mentalfloss.com/article/63098/black-sunday-storm-gave-us-dust-bowl. Accessed April 11, 2018.

DeMott, Robert. 2009. Grapes of Wrath, a classic for today? BBC News, 14 April 2009. Available at: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/7992942.stm. Accessed April 11, 2018.

Greenspan, Jesse. 2015. Remembering Black Sunday, 80 Years Later. History.com, April 14, 2009. Available at: https://www.history.com/news/remembering-black-sunday-80-years-later.

National Weather Service. The Black Sunday Dust Storm of April 14, 1935. Available at: https://www.weather.gov/oun/events-19350414. Accessed April 11, 2018.

Natural Resources Conservation Service. More Than 80 Years Helping People Help the Land: A Brief History of NRCS. Available at: https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detail/national/about/history/?cid=nrcs143_021392. Accessed April 11, 2018.