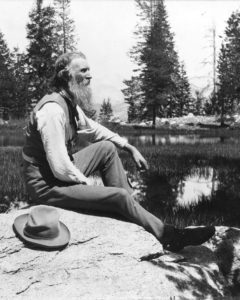

Think about your image of John Muir. Probably a thin old man with a long scraggly beard, walking by himself in the wilderness, as far from polite society as he could get. True, but certainly not the whole truth. John Muir, the Father of American Conservation, was much more than a hermit.

John Muir was born in Dunbar, Scotland, on April 21, 1838 (died 1914). He was raised in a strict home by a fervently religious and strict father. Muir, however, disobeyed as often as possible, sneaking off to the forbidden seaport or out into the fields. He was all boy, and his behavior elicited one response by an observer: “The verra Deevil’s in that boy.”

When he was 11, Muir moved with his family to Wisconsin to start life as pioneer farmers. It was a hard life, but Muir loved it. Hard work and physical discomfort never bothered him, and he loved the near-wilderness of rural Wisconsin. He read books smuggled into the house from neighbors, dreaming to follow the South American adventures of explorer Alexander von Humboldt.

He was a clever young man, figuring out ways to do the farm work more efficiently and inventing machines to help ease the labor. He built a mechanical bed fitted with an alarm clock; when the alarm triggered, the bed tilted up and slid the sleeper onto the floor. When he displayed this and other inventions at the Wisconsin State Fair in Madison, people declared that Muir was not a devil, but a genius.

He tried college for a couple of years, but never completed a degree. A pacifist, he walked to Canada to avoid the draft during the Civil War—starting his practice of walking wherever he needed to go. After the war, he returned to the U.S., working in a wheel factory in Indianapolis. Again, his genius for mechanics and logistics made him a success, and he was on track to marry and become a rich industrialist.

But one day an accident at the factory left him temporarily blinded. He decided then to change his life: “I might have become a millionaire,” he wrote, “but I chose to become a tramp.” And tramp he did, walking a thousand miles from the Midwest to Florida. He boarded a ship to take him to South America, but changed his mind and headed to California.

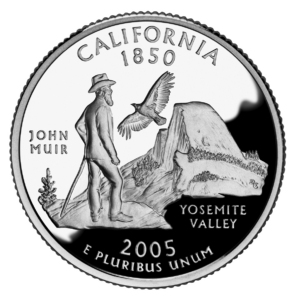

In California, he walked east to the Yosemite Valley, and his fate was sealed. He fell in love with the mountains and valleys of the Sierra Nevada, living in the Yosemite Valley for several years. He began to write, and his style of describing manly wilderness adventures in popular magazines captured America’s imagination. He became famous and wealthy.

Muir was a complex man. He was deeply spiritual, but hated organized religion. He loved people individually and was the life of the party wherever he went, but he distrusted organizations of all kinds. He never considered himself a citizen of anything but the earth. He loved hiking in the wilderness alone, but craved the company of those he loved.

Muir was a complex man. He was deeply spiritual, but hated organized religion. He loved people individually and was the life of the party wherever he went, but he distrusted organizations of all kinds. He never considered himself a citizen of anything but the earth. He loved hiking in the wilderness alone, but craved the company of those he loved.

He married and had two daughters, a happy man in a happy family. For a decade, Muir ran his father-in-law’s farm and vineyards, never writing and seldom hiking. But his wife knew that he still needed the chance to roam the wilderness, and she encouraged him to re-balance his life. He again picked up his walking stick and his pen.

Along the way he grew increasingly concerned about what was happening to his beloved mountains. Excessive logging, over-grazing and shabby tourism were destroying the beauty and productivity of nature. In cahoots with his publishing colleague, Robert Underwood Johnson, Muir mounted a movement to protect the Yosemite ecosystem. With Muir writing and Johnson lobbying, they succeeded—Yosemite National Park was created in October, 1890.

From then on, Muir became a conservationist first and a writer and hiker second. He traveled more widely, up to Alaska and down to the desert southwest. He became close friends with Teddy Roosevelt, and persuaded him to protect other precious landscapes that were being overrun, including the Grand Canyon. For once overcoming his reluctance for organizations, he helped found The Sierra Club and served as its president until the end of his life.

His victories for conservation are legion, but one failure plagued him. He considered the Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite National Park as beautiful as the Yosemite Valley itself. When a proposal arose to flood the valley to supply water to San Francisco, Muir fought what he considered a mortal sin: “Dam Hetch Hetchy! As well dam for water-tanks the people’s cathedrals and churches, for no holier temple has ever been consecrated by the heart of man.” But Muir lost, and that disappointment, added to his revulsion at the start of World War 1, broke his spirit. He died the day before Christmas, 1914.

Reference:

Nielsen, Larry A. 2017. Nature’s Allies: Eight Conservationists Who Changed Our World. Island Press, Washington, DC 255 pages.