If you go to a state or national park, you will probably be walking on a trail, sitting in a shelter or standing on a scenic overlook that was built in the 1930s by the young workers of the CCC—the Civilian Conservation Corps. The CCC is one of the great American success stories of conservation, a silver lining from the cloud of the Great Depression.

In the early 1930s, America was in the worst economic conditions in history. Unemployment was nearly 25%, and half of young men were out of work. At the same time, the country’s natural resources had been devastated by soil erosion, forest over-harvesting and loss of wildlife habitat.

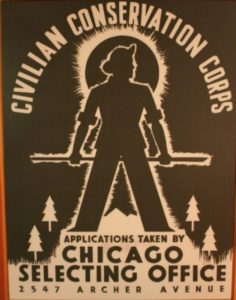

As soon as Franklin Roosevelt was elected president, he asked Congress to give him authority to address both those problems by creating the Emergency Conservation Work Act, which we know as the Civilian Conservation Corps, or CCC. Congress did so on March 31, 1933, and Roosevelt issued Executive Order 6101 creating the CCC on April 5. He appointed Robert Fechner, a union leader, as the director.

They wasted no time. Two days later, the CCC started enrolling young men into the program. It was a military-style operation. Only unemployed young men, aged 18-25, were eligible. They lived in wooden barracks or tents, in camps throughout the country. They were given uniforms and their meals in exchange for six days of hard work per week. They were paid $30 per month, but $25 of that was sent back to their families to relieve the desperate situations at home. Participants “enlisted” for at least six months, but many spent years in the program.

Within a year, more than 250,000 men were operating in the CCC, growing to a high of 500,000 at one time in 1935. In total, over the life of the CCC from 1933 to 1942, more than 3 million men participated. Most were white, but as the program developed, segregated camps for minorities were started, serving about 250,000 African-Americans and 80,000 Native Americans. In later years of the program, women were also allowed to participate (about 8500 overall).

The CCC was immensely popular. Thousands of camps were eventually established in all 48 states and Alaska, Hawaii, Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. Both Republicans and Democrats endorsed the program, and local politicians loved the money it brought to their communities. The participants became healthier and learned skills; many took educational courses in the evenings, including an estimated 57,000 illiterate men who learned to read. The money sent home improved life there. In the communities near camps, the labor needed to build and maintain the camps created jobs and economic activity.

But the real winner was conservation. Over the nine years of the program, the CCC created an enormous legacy. The men built 3470 fire towers, cleared 97,000 miles of fire roads and spent more than 4 million man-days fighting fires. Long before FEMA, they provided the workforce to help victims of floods, hurricanes and other natural disasters.

Known as “Roosevelt’s Tree Army,” they planted three billion trees, representing half of all reforestation that has occurred in the U.S. The CCC established 711 new state parks and built the roads, campgrounds and picnic areas within them and another 170 state, county and municipal parks. Nearly 200 CCC camps were within national parks and monuments, responsible for most of the infrastructure in those parks.

While many leaders wanted to establish the CCC as a permanent part of the federal government, a more immediate threat arose—the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. As the U.S. entered World War II, the country realized that young men were needed most for the war effort. And, so, in early 1942, the CCC was shut down.

The CCC may be a part of history today, but the legacy lives on. Similar programs have followed in various forms, at both federal and state levels, for conservation and other societal purposes. So, whenever you walk a trail in a park, or marvel at the craftsmanship of the beautiful stone bridges, cabins and visitor centers in one of our national parks, remember the young workers of the CCC—and thank both them and the foresighted leaders of our country for their commitment to our future.

References:

Civilian Conservation Corps Legacy. CCC Brief History. Available at: http://www.ccclegacy.org/CCC_Brief_History.html. Accessed April 5, 2018.

Digital Public Library of America. Roosevelt’s Tree Army: The Civilian Conservation Corps. Available at: https://dp.la/exhibitions/civilian-conservation-corps/history-ccc. Accessed April 5, 2018.

History.com. Civilian Conservation Corps. Available at: https://www.history.com/topics/civilian-conservation-corps. Accessed April 5, 2018.

Paige, John C. 1985. The Civilian Conservation Corps and The National Park Service, 1933-1942, An Administrative History. National Park Service. Available at: https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/ccc/index.htm. Accessed April 5, 2018.