When you walk into Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History, you are met by two gigantic African elephants, locked in battle. When you walk around the mammal hall at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, you see a series of magnificent displays of African wildlife in natural settings. Whenever you observe a diorama of a natural history scene anywhere, you are witnessing the legacy of Carl Akeley.

Carl Ethan Akeley was born on May 19, 1864, in Clarendon, New York (died in 1926). He cared little for the work of the family farm, but fell in love with animals and was intrigued by the possibility of preserving them after they died. At 12, he stuffed his first specimen, a friend’s canary—he wanted to bring her comfort by preserving the animal so it could continue to be with her. He never was far from taxidermy for the remainder of his life.

After leaving high school, he moved to Rochester and began work for Ward’s Natural Science Establishment, which collected and prepared specimens for museums. Akeley quickly learned the trade, but disparaged it, calling the current practice as the “upholsterer’s method of mounting animals.” Skins were stuffed with sawdust, cotton and straw into the vague shape of an animal, sewn together and dropped on their straightened legs.

His big break came when P.T. Barnum asked Ward’s to preserve the memory of the famous elephant, Jumbo, which had been killed in a railroad accident. Akeley and a colleague, J. William Critchley, worked for five months on the project, creating a new style of taxidermy. They built up the body from bones or wooden and steel elements, sculpted the elephant’s body in clay, sprayed it with wet cement, and stretched the skin over it, making a realistic and gigantic mount. A new, naturalistic era of taxidermy began.

Two years later, Akeley moved to the Milwaukee Public Museum and began making realistic dioramas of animals in their natural habitats. His success there led to his employment by the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago in 1896. While there, he made several trips to Africa to collect specimens. During a trip in 1905, he and his wife, Delia, shot the two elephants that still stand in the central hall of the museum.

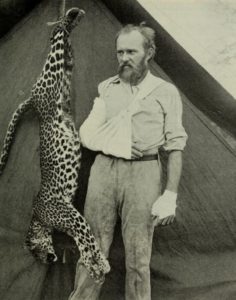

But it was his first trip to Africa, in 1896, that made Akeley a bit of a legend. While shooting what he thought was a warthog, he wounded a leopard. The leopard charged Akeley, biting him in the hand. Rather than trying to escape the jaws, Akeley jammed his fist down the leopard’s throat and used his other arm to attempt strangling the animal. They wrestled to exhaustion, with Akeley finally outlasting the leopard.

In 1909, Akeley moved to the American Museum of Natural History, where he worked for the rest of his life (taken ill on an African expedition in 1926, he died and was buried in Africa). His approach to taxonomy reached its zenith at the New York museum, now permanently displayed in a series of 28 dioramas in the Akeley Hall of African Mammals.

The secret to his mastery of taxidermy lay beneath the skin. He was actually a sculptor. He studied animals alive in the field and took careful measurements of the animal carcasses. He also was a sculptor, creating life-sized pieces in bronze (a pair still stand in the central hall of the American Museum of Natural History). He was an inventor, also, with dozens of patents. One was for an improved motion-picture camera that replaced the bulky machines he had to take to Africa on early trips. Another was a cement sprayer to cover his clay sculptures that is still used in commercial applications.

Today, killing animals to display them seems barbaric, but when Akeley began working, it was considered an act of conservation. Africa was being rapidly developed by colonial nations, and African wildlife was disappearing at astonishing rates. Neither zoos nor photography were considered adequate to educate the public about wildlife, but museum dioramas could serve that purpose. Fearing the extinction of African species before the developed world could see or study them, museums took the desperate step of hunting them. So, like Audubon a century before, Akeley and his colleagues shot rare and precious animals and brought their remains back to the great museums of the world.

But Akeley realized that more was needed than simply showing people dead animals in artificial settings. One of his most important taxidermy projects created a display of mountain gorillas, using specimens he shot in the Belgian Congo. His motives were pure: “I have been constantly aware of the rapid and disconcerting disappearance of African wildlife. [This] gave rise to the vision of the culmination of my work in a great museum exhibit, artistically conceived, which should perpetuate the animal life, the native customs, and the scenic beauties of Africa.” But it was also one of his most heart-rending projects. After wounding an immature gorilla, he said, “I came up before he was dead. There was a heartbreaking expression of piteous pleading on his face. He would have come to my arms for comfort.” Over time, Akeley was haunted by the feeling that he was a murderer.

Observing mountain gorillas in the Belgian Congo, Akeley realized that conserving the habitat of the animals was more important than collecting them. He worked tirelessly to convince King Albert of Belgium that this portion of the Congo should be preserved for mountain gorillas. In 1925, the government established a 200-square-mile gorilla sanctuary. That sanctuary has grown into the 3,000-square-mile Virunga National Park, home to a majority of the world’s remaining mountain gorillas. Without Akeley’s persistence, most experts believe the mountain gorilla would now be extinct.

References:

American Museum of Natural History. 2016. The Man Who Made Habitat Dioramas. Available at: https://www.amnh.org/explore/news-blogs/news-posts/the-man-who-made-habitat-dioramas/. Accessed May 17, 2018.

Barclay, Bridgitte. 2015. Through the Plexiglass: A History of Museum Dioramas. The Atlantic, Oct 14, 2015. Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2015/10/taxidermy-animal-habitat-dioramas/410401/. Accessed May 17, 2018.

NPR. 2010. Wrestling Leopards, Felling Apes: A Life in Taxidermy. Available at: https://www.npr.org/2010/12/04/131107085/wrestling-leopards-felling-apes-a-life-in-taxidermy. Accessed May 17, 2018.

The Field Museum. Carl Akeley. Available at: https://www.fieldmuseum.org/about/history/carl-akeley. Accessed May 17, 2018