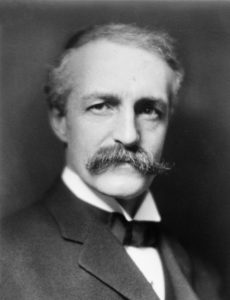

“Conservation means the greatest good to the greatest number for the longest time.” The man who coined that sentence, adding “for the longest time” to the end of a long-used democratic sentiment, was Gifford Pinchot, the country’s first professional forester and the father of the profession.

Gifford Pinchot was born on August 11, 1865, in Connecticut (died 1946). His family was wealthy, made rich by lumber manufacturing, real estate brokering and importing fancy French wallpaper for upper-class homes. He received the best education money could buy, including an undergraduate degree from Yale and repeated European travel. But he was always attracted more to the outdoors than he was to the schoolroom. Eventually his father, seeking a future for his son that would build on his happiness in the woods, asked Pinchot, “How would you like to be a forester?” He jumped at the chance.

No training existed in the U.S. at the time, so Pinchot journeyed to Nancy, France, to study at their National Forestry School. He learned the principles of European forestry, including selective harvesting and silviculture—the planting and care of forest trees. Cutting his schooling short so he could start practicing forestry, he returned home after one year and began work as a professional consulting forester—the first in the nation’s history.

His big break came in 1892 when George Vanderbilt hired Pinchot to manage the forests on his sprawling estate in Asheville, North Carolina. Pinchot was given wide latitude, creating a forest management plan modeled in the European style but with changes unique to American trees, landscape and climate. He specified all aspects of management—which trees to grow, how dense to plant them, when and how much to thin, what to expect in terms of growth and yield. He hired a German silviculturist, Carl Schenck, to conduct the work directly.

His efforts led to broad recognition, and he was appointed to the Forest Commission of the National Academy of Sciences in 1886. That commission recommended that the federal government create what we now call national forests, recognizing the need for more pro-active management of the public lands. Two years later, President McKinley appointed Pinchot as the chief of the Division of Forestry, responsible for carrying out the commission’s recommendations.

Pinchot continued in this role when Teddy Roosevelt succeeded McKinley as president. The partnership of Pinchot and Roosevelt is the stuff of legends—both vigorous outdoorsmen, both ambitious and tireless, both committed to the idea of conservation. When Roosevelt created the US Forest Service in 1905, he appointed Pinchot its leader, the first Chief Forester of the United States. He stayed in the position until 1910, when Taft succeeded Roosevelt.

Pinchot used his opportunity as chief forester to the fullest. He expanded national forests from 32 to 149 and from 75 to 193 million acres. He arranged for national forests to be transferred from the Department of Interior to his own agency in the Department of Agriculture. He increased the agency’s professional staff by an order of magnitude, hiring virtually every graduate forester the country produced. And virtually all of those were produced at Yale University, graduating from the School of Forestry that Pinchot founded with his brother in 1900. In the same year, he helped found the Society of American Foresters, still the nation’s premier scientific and professional forestry organization.

Along the way, Pinchot also established the principles that drove conservation—of forests, wildlife, fisheries, soil and water—for most of the 20th Century. In his 1910 book, The Fight for Conservation, Pinchot established that conservation was about the wise use of resources. Natural resources should not be wasted and overused, but neither should they be squandered by lack of use. He wrote, “Conservation demands the welfare of this generation first, and afterward the welfare of generations to follow.” This has come to be known as the “gospel of efficiency,” as controversial then as it is today. John Muir, for example, split with Pinchot over the question of preserving at least some forests without using them, and Aldo Leopold re-framed Pinchot’s idea of “use” by adding preservation (or non-use) as a legitimate kind of “use” for some lands.

Pinchot also deserves great credit for moving the idea of conservation into the mainstream of political and philosophical thought in the United States. He wrote about the importance of conservation in all parts of life:

“The principles of conservation thus described—development, preservation, the common good—have a general application which is growing rapidly wider. The development of resources and the prevention of waste and loss, the protection of the public interest, by foresight, prudence, and the ordinary business and home-making virtues, all these apply to other things as well as to the natural resources. There is, in fact, no interest of the people to which the principles of conservation do not apply.”

Pinchot followed his career in national forestry matters by a career as a politician. He helped Teddy Roosevelt form the Bull Moose Party and lobbied for the party’s progressive ideas. He was twice elected governor of Pennsylvania. As governor, he worked tirelessly for rural development and the common person. He built 20,000 miles of rural roads in his state, known then and now as “Pinchot Roads.” He greatly expanded Pennsylvania’s state park program, with the goal of having a state park accessible for every citizen for day-use.

Pinchot died in 1946, aged 81. His home, Grey Towers, in eastern Pennsylvania, was donated to the US Forest Service as a museum and educational center. A national forest in Washington was re-named for Pinchot. The highest honor in the Society of American Foresters is called the Gifford Pinchot Medal, awarded bi-annually. All fitting for the father of American forestry.

References:

Dennehy, Kevin. First Forester: The Enduring Conservation Legacy of Gifford Pinchot. Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies. Available at: http://environment.yale.edu/news/article/first-forester-the-conservation-legacy-of-gifford-pinchot/. Accessed June 13, 2018.

Encyclopedia Britannica. Gifford Pinchot. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Gifford-Pinchot. Accessed June 13, 2018.

Pinchot, Gifford. 1910. The Fight for Conservation. University of Washington Press, Seattle. (facsimile printing 1967). 152 pages.

U.S. Department of Interior. 2017. Gifford Pinchot: A Legacy of Conservation. Blog, 8/9/2017. Available at: https://www.doi.gov/blog/gifford-pinchot-legacy-conservation. Accessed June 13, 2018.

Wilderness Connect. Gifford Pinchot: America’s First Forester. Available at: https://www.wilderness.net/nwps/Pinchot. Accessed June 13, 2018.