August 27 is known in some circles as Oil and Gas Industry Appreciation Day. It’s a pretty low-key affair, and I can’t find information about why the industry picked August 27—but I think I know the reason. This date, in 1859, is also when Edwin Drake drilled the first successful oil well in the world.

Interest about oil had been growing for some time. It oozed out of the ground in various places, including far northwestern Pennsylvania. People had been making kerosene for lamps from coal, but chemists had figured out how to make kerosene from oil, a far easier process than converting coal to a liquid. Others discovered—maybe—that oil was an elixir that could cure a variety of ailments, including the dreaded “consumption” (now we call it tuberculosis).

But finding oil in commercial quantities was tough. The basic method was to gather it from pools on the ground where it seeped to the surface, a process that might yield a few quarts a day. Drilling with traditional techniques used for water wells or brine wells (used to bring dissolved salt to the surface) failed to produce oil. The Seneca Oil Company of Connecticut was founded to develop new techniques, and they hired retired Edwin Drake to lead the efforts in northwestern Pennsylvania.

Drake was born in New York in 1819. He became a railroad conductor, running routes in New York and Pennsylvania. He developed a debilitating muscular condition and after eight years on the railroad, was forced to retire. Unemployed, he and his family moved to Titusville, Pennsylvania. Drake knew one of the owners of the Seneca Oil Company and when they met by chance in Titusville, Drake was offered the job to manage their oil-drilling efforts.

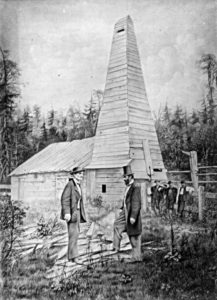

Drake set up shop in Titusville, Pennsylvania. Working with an experienced local well driller, William Smith, Drake spent months trying and failing to perfect a drilling technique. His efforts earned the local nickname “Drake’s Folly.” Eventually, investors abandoned Drake, and his workers began to doubt his sanity, calling him “Crazy Drake.” But his drilling innovation—a pipe that surrounded the drill bit and kept the bore hole stable—made the difference. Drilling three feet per day, they stopped on the evening of August 26, 1859, when the well was 69.5 feet deep. The next morning, oil had floated to the top of the hole—and history had been made!

The well was soon producing 40 barrels of oil per day. One observer noted that Drake’s well could produce in a few days the same amount of oil as a whaling ship on a four-year voyage. Western Pennsylvania became the center of the oil industry, producing half of the world’s supply for the next 40 years. Colonel Drake (he was not a military man, but adopted the rank anyhow) went from a goat to a hero.

From that first oil well (which is now part of a fascinating museum at the site), of course, the modern world has been built upon an oil and gas economy. More than 4 million oil wells have been drilled in the U.S. alone. Oil supplies one-third of all the energy consumed worldwide, and 98% of fuel used for transportation. The world consumes 1.5 million gallons of oil products (gasoline, diesel and kerosene, primarily) per minute. Per minute! That’s about 50 million barrels, or 2 billion gallons, per day.

Americans love our cars, and the rest of the world is growing to love theirs. About 1.2 billion cars are traveling the world’s roads now, and that number will continue to rise. Americans have about 82 cars per 100 people, while China has about 7 and India about 4. As other forms of transportation develop, other fuel uses will also increase. Consumption of jet fuel, for example, has doubled in the last two decades.

And despite dire warnings about running out of oil, that isn’t about to happen anytime soon. Petroleum scientists keep discovering new sources of oil, so that reserves have not changed in decades, despite increasing extraction. Drake’s first oil well was step one of a seemingly unending process of finding more sources of oil in more places throughout the world.

Oil has been one of several sources of our advanced society, with high quality of life for increasing billions of people. But, of course, there is a dark side. Burning oil produces greenhouse gases. While coal is the worst fuel to burn in terms of CO2 emissions per energy unit produced (over 200 pounds per BTU), diesel and gasoline come in second (around 150 pounds per BTU). China today emits the most greenhouse gases (about 28% of the total); the U.S. is second with 16.5%, and the European Union is third, with 11.4%. Rounding out the top ten emitters are India, Russia, Japan, South Korea, Iran, Canada and Saudi Arabia. Together, the top ten emit 78% of the world’s greenhouse gases.

So, two lessons remain clear. First, there is still a lot of oil and the world’s economy still runs on it. Second, if we are going to slow down or stop climate change, we have to reduce the impact of burning fossil fuels—either with new technologies to reduce emissions or alternative fuels to replace oil and gas. What we need, I think, is a new generation of Edwin Drakes, willing to be called crazy as they work to make our world sustainable.

References:

American Oil & Gas Historical Society. First American Oil Well. Available at: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/american-oil-history/. Accessed July 7, 2018.

Clemente, Jude. 2015. Three Reasons Oil Will Continue to Run the World. Forbes Magazine, April 19, 2015. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/judeclemente/2015/04/19/three-reasons-oil-will-continue-to-run-the-world/#325d13f143f9. Accessed July 7, 2018.

Davooe, Urja. 2008. Edwin Drake and the Oil Well Drill Piple. Pennsylvania Center for the Book. Available at: https://pabook.libraries.psu.edu/literary-cultural-heritage-map-pa/feature-articles/edwin-drake-and-oil-well-drill-pipe. Accessed July7, 2018.

Friedrich, Johannes and Thomas Damassa. 2014. The History of Carbon Dioxide Emissions. World Resources Institute, May 21, 2014. Available at: http://www.wri.org/blog/2014/05/history-carbon-dioxide-emissions. Accessed July 7, 2018.

U.S. Energy Information Administration. How much carbon dioxide is produced when different fuels are burned? Available at: https://www.eia.gov/tools/faqs/faq.php?id=73&t=11. Accessed July 7, 2018.