At the turn of the 20th Century, forestry was a one-way business: Cut-out and get-out. Loggers removed all the trees from a forest, left the land to an unknown future, and headed to the next virgin forest. It happened first in the northeastern quadrant of the U.S., and the south was next on the menu. One man, Henry Hardtner, decided that wasn’t the way to manage Louisiana’s forests—and became the “Father of Southern Forestry.”

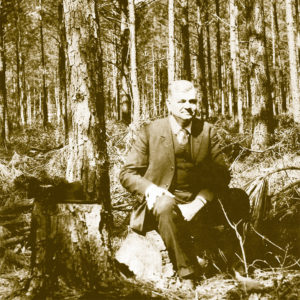

Henry Hardtner was born in central Louisiana on September 10, 1870 (died 1935). After a youth spent roaming the woods, he joined his father’s fledging logging business in the small community of Olla, Louisiana. They named their land and company Urania, after the Greek muse of astronomy. In 1906, Hardtner became the majority owner and leader of the company. He had no training in forestry (no one had in the U.S. at that time), but had an innate feel for the forest:

“I was born in the forests and have had close association with them since childhood. What I know of them cannot be learned in schools or colleges. To me they are as humans and I know the trees as I try to know men.”

Knowing the trees gave Hardtner a different perspective on the forestry business. He recognized that cutting trees and then abandoning the land was wasting the future. He believed that a crop of trees could be regrown in a reasonable number of years—about 40, say—because young trees would grow faster than the original and old longleaf pine that the industry was harvesting. So, he began three practices on his land that today we recognize as sustainable forestry but were then unheard of. First, he protected the forest from arson (which was common in Louisiana) by hiring fire wardens to patrol the woods. Second, he demanded that all trees reaching his mills had to be above a certain diameter, protecting the smaller trees in the woods. Third, he required loggers to leave several mature trees per acre to re-seed the harvested land.

All of his ideas were revolutionary at the time, and no data existed to support him. So, Hardtner set up what became essentially a forestry experiment station on his Urania property. He monitored the regeneration on his lands, measuring the density and growth of his “baby pines” in relation to harvesting practices.

His peers thought him a “foolish visionary” who would soon be out of business. But Hardtner was as shrewd a businessman as he was a conservationist. He cut his virgin woodlands at a slow, steady pace, providing the resources to keep his experiments in regeneration going. And as new forests began to grow and mature on his lands, others began to take notice. Over the years, Urania became a destination for foresters from across the nation and world. Yale sent their forestry students to Louisiana to see what Hardtner was accomplishing. He ran demonstrations for visitors to his forests, soon earning the title of “Moses of Forestry.” The foolish visionary turned into the leader of modern forestry in Louisiana and throughout the south.

At the same time, Hardtner worked vigorously for regulation of forest harvesting, investments in forest management, and the development of forestry research. In 1904, he used his political connections to help pass Louisiana’s first forestry law, with provisions that matched his own forestry practices. When Louisiana created a Commission for the Conservation of Natural Resources in 1908 (after the governor returned from Teddy Roosevelt’s Governors Conference on Conservation) (learn more about the conference here), Hardtner was appointed its first chair. Eventually, he convinced the commission to appoint a state forester and create an independent forestry agency. He worked to establish the idea of “reforestation contracts,” which provided tax benefits if landowners agreed to re-forest their land and let the trees grow for 40 years. Hardtner signed the first contract issued by the state in 1913, covering more than 25,000 acres of his own land.

Hardtner wrote extensively about forestry and led many forestry organizations. He co-founded the Louisiana Forestry Association and the Southern Forestry Congress, serving as presidents of both groups. In 1999, the Southern Group of State Foresters established the Henry Hardtner Award to recognize sustainable forestry and conservation on non-industrial private forest lands. The great respect that Hardtner earned during his life and since his death is exemplified by the words of a representative of the U.S. Forest Service at the dedication of a memorial to him in 1939:

“Just as occasionally a tree springs in an opening in the forest and establishes its roots in deep fertile soil beside a stream and grows to tower above all its associated, so it happens occasionally with men. Today we pay homage and are here to dedicate a memorial to the life and achievement of such a man—Henry Ernest Hardtner.”

References:

Barnett, Jim. 2017. Making Southern forests great again. Louisiana Forestry Association, 3/27/2017. Available at: https://laforestry.com/News/tabid/112/ArticleID/57/Making-Southern-forests-great-again.aspx. Accessed July 18, 2018.

Burns, Anna C. 1978. Henry E. Hardtner, Louisiana’s First Conservationist. Journal of Forest History 22(2):78-85. Available at: https://www-jstor-org.prox.lib.ncsu.edu/stable/pdf/3983330.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A4bb66f294651b782094b5e38f8904747. Accessed July 18, 2018.

Fickleis, James E. 2001. Early Forestry in the South and in Mississippi. Forest History Today, Spring/Fall 2001:11-18. Available at: https://foresthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/fickle_early-forestry-in-south-and-mississippi.pdf. Accessed July 18, 2018.

Mattoon, Wilbur R. 1939. Dedication Address to Henry E. Hardtner. Journal of Forestry 37(10):761-762. Available at: https://academic.oup.com/jof/article-abstract/37/10/761/4721285?redirectedFrom=PDF. Accessed July 18, 2018.